No. 1 risk for child stunting in developing world: Poor growth before birth

In a new Canadian-funded study, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health researchers today rank for the first time a range of risk factors associated with child stunting in developing countries, the greatest of which occurs before birth: poor fetal growth in the womb.

Based on their findings, they prescribe fundamental changes in approaches to remedy stunting, which today largely focus on children, calling for greater emphasis on interventions aimed at mothers and environmental factors such as poor water and sanitation and indoor biomass fuel use.

Funded by the Government of Canada through Grand Challenges Canada's "Saving Brains" program, the study reports that in 2011 some 44 million (36 percent) of two-year-olds in 137 developing countries were stunted, defined as being two or more standard deviations shorter than the global median. About one quarter (10.8 million) of those stunting cases were attributable to full-term babies being born abnormally small.

The findings highlight a need for more emphasis on improving maternal health before and during pregnancy, according to the researchers at Harvard Chan School, who published their work today in PLOS Medicine.

The absence of optimal sanitation facilities that ensure the hygienic separation of human waste from human contact has the second largest impact overall, attributable to 7.2 million stunting cases (16.4 percent), followed in third place by childhood diarrhea, to which 5.8 million cases (13.2 percent) are attributed.

Child nutrition and infection risk factors accounted for six million (13.5 percent) of stunting cases overall.

Teenage motherhood and short birth intervals (less than two years between consecutive births) had the fewest attributable stunting cases of the risk factors that were analyzed—860,000 (1.9 percent) of cases overall.

The study concludes that reducing the burden of stunting requires continuing efforts to diagnose and treat maternal and child infections, especially diarrhea, and "a paradigm shift...from interventions focusing solely on children and infants to those that reach mothers and families."

Says lead author Goodarz Danaei, Assistant Professor of Global Health at Harvard Chan School: "These results emphasize the importance of early interventions before and during pregnancy, especially efforts to address malnutrition. Such efforts, coupled with improving sanitation and reducing diarrhea, would prevent a substantial proportion of childhood stunting in developing countries."

"This is a serious problem at every level, from individual to national," he adds. "Early life growth faltering is strongly linked to lost educational attainment and the immense cost of unrealized human potential in the developing world. Stunting undermines economic productivity, in turn limiting the development of low-income countries."

While previous research identified a large number of nutrition-specific risk factors for stunting, such as preterm birth, zinc deficiency, and maternal malaria, the relative contribution of these risk factors had not been consistently examined across countries.

"Our findings provide further evidence that integrated nutrition-sensitive interventions, such as improved water and sanitation, are warranted in addition to nutrition-specific interventions to have an impact on the risk of stunting globally," says senior author and Principal Investigator Wafaie Fawzi, Professor and Chair of the Department of Global Health and Population at Harvard Chan School.

In all, 18 risk factors, selected based on the availability of data, were grouped into five categories and ranked:

- Poor fetal growth and preterm birth,

- Environmental factors, including water, sanitation and indoor biomass fuel use,

- Maternal nutrition and infection,

- Child nutrition and infection, and

- Teenage motherhood and short birth intervals (less than two years between child births).

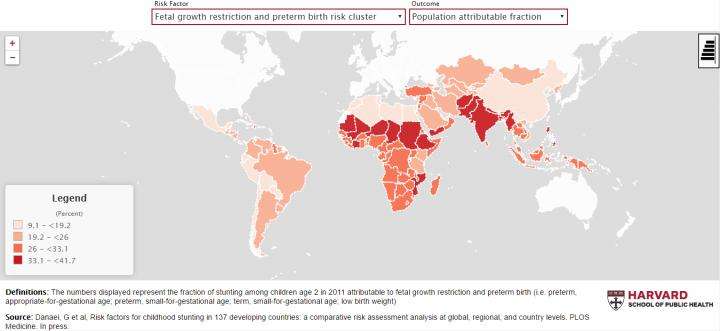

The researchers map the burden of stunting attributable to these risk factors in the developing world on a website, healthychilddev.sph.harvard.edu, helping policy makers visualize important differences across regions, sub-regions and countries.

"These findings can help regions and countries make evidence-based decisions on how to reduce the burden of stunting within their borders," says Professor Danaei.

Findings at the regional level include:

- Environmental factors, such as water, sanitation and indoor biomass fuel use, are the second leading risk category in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Pacific.

- Poor child nutrition and infection is the second leading risk category in Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, North Africa and the Middle East.

- Among Sub-Saharan African countries, the prevalence of stunting associated with poor sanitation in Central, East and West Africa is more than double that of southern Africa.

- Childhood diarrhea was associated with almost three times the burden of stunting in Andean and central Latin America compared with tropical and southern Latin America.

- Somalia had the largest prevalence of stunting attributable to breastfeeding that was discontinued before a child reaches 6-24 months of age.

The new study follows the publication of two major studies focused on poor child growth and developmental milestones by the same Canadian-funded "Saving Brains" team at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The first study, published in PLOS Medicine on June 7, 2016, found that one-third of three- and four-year-olds in low- and middle-income countries fail to reach basic milestones in cognitive and/or socio-emotional growth.

The second study, published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition on June 29, 2016, found that poor child growth costs the developing world US$177 billion in lost wages and 69 million years of educational attainment for children born each year.

"Knowing the major risk factors for stunting, the global cost of poor child growth, and the number of children missing developmental milestones are key pieces of information in ensuring children not only survive, but thrive," says Dr. Peter A. Singer, Chief Executive Officer of Grand Challenges Canada.

"This kind of information is essential to achieving the targets set out by the Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy for Women's, Children's, and Adolescent's Health. If you are a finance minister, you will want to check out the risk factors for stunting to reduce the toll on human capital and GDP in your country."

The importance of children thriving, not just surviving, is emphasized in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and is central to the Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescent's Health. In 2014, the World Health Assembly set a target to reduce by 40 percent the number of stunted children worldwide by 2025.

More information: Goodarz Danaei et al, Risk Factors for Childhood Stunting in 137 Developing Countries: A Comparative Risk Assessment Analysis at Global, Regional, and Country Levels, PLOS Medicine (2016). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002164