Surging prescriptions, deaths: Australia faces opioid crisis

Half a world away from the opioid epidemic ravaging the United States, Australia is facing a crisis of its own, with skyrocketing rates of opioid prescriptions and related deaths.

The country has failed to heed the lessons of the U.S., and has been slow to respond to years of warnings from worried health experts. The crisis comes as drug companies—facing scrutiny for their aggressive marketing of opioids in America—have turned their focus abroad, working around marketing regulations to push the painkillers in other countries.

In dozens of interviews, doctors, researchers and Australians whose lives have been upended by opioids described a plight that now stretches from coast to coast. Australia's death rate from opioids has more than doubled in just over a decade. And health experts worry that without urgent action, Australia is on track for an even steeper spike in deaths like those in America, where the epidemic has left 400,000 dead.

"It's depressing at times to see how we, as practitioners, literally messed up our communities," said Dr. Bastian Seidel, who warned that Australia's opioid problem was a "national emergency" two years ago when he was president of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. "It's our signature on the scripts."

He sees Australia moving with willful ignorance toward a disaster.

"Unfortunately, in Australia, we've followed the bad example of the U.S.," he says. "And now we have the same problem."

Starting in 2000, Australia began approving and subsidizing certain opioids for use in chronic, non-cancer pain. Those approvals coincided with a spike in opioid consumption, which nearly quadrupled between 1990 and 2014, says Sydney University researcher Emily Karanges.

As opioid prescriptions rose, so did fatal overdoses. Opioid-related deaths jumped from 439 in 2006 to 1,119 in 2016—a rise of 2.2 to 4.7 deaths per 100,000 people, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

More than 3 million Australians - an eighth of the country's population - are getting at least one opioid prescription a year.

In the U.S., drug companies such as OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma are facing more than 2,000 lawsuits accusing them of overstating the benefits of opioids and downplaying their addictiveness.

In Australia, pharmaceutical companies by law cannot directly advertise to consumers, but can market drugs to medical professionals. And they have done so, aggressively and effectively, by sponsoring swanky conferences, running doctors' training seminars, funding research papers and meeting with physicians to push the drugs for chronic pain.

"If the relevant governing bodies had ensured that the way the product was being marketed to doctors especially was different, I don't necessarily think we would see what we're seeing now," says Bee Mohamed, who until recently was the CEO of ScriptWise, a group devoted to reducing prescription drug deaths in Australia. "We're trying to undo ten years of what marketing has unfortunately done."

Mundipharma, the international arm of Purdue that Purdue's owners have proposed selling to help pay for a settlement in the U.S., has received particular criticism for its marketing tactics in Australia. Mundipharma also runs "Pain Management Master Classes," which have provided training to more than 5,000 doctors in Australia. The classes have been praised by some as helpful and condemned by others as a conflict of interest.

Mundipharma said the classes cover non-opioid treatment options and "strongly emphasize" that opioids are only appropriate after a comprehensive assessment. In a statement, it also said it strictly adheres to the code of conduct of the pharmaceutical industry's regulator, Medicines Australia, and has always been transparent about the risks associated with opioids.

Like in the U.S., the problem has hit the country's poorest areas the hardest. One region of Tasmania—Australia's poorest state—has the highest number of government-subsidized opioid prescriptions in the nation: more than 110,000 for every 100,000 people.

In poor, rural areas, access to pain specialists can be logistically and financially difficult. Wait lists are long, and a few sessions with a physiotherapist can cost hundreds of dollars. Under the government-subsidized prescription benefit plan, a pack of opioids costs as little as AU$6.50 ($4.50.)

It's a system that has made opioids the cheap and easy alternative for Australians, particularly the poor.

For years, Tasmanian Carmall Casey sought treatment for knee pain, only for doctors to send her away with prescriptions for opioids. When her pain returned, the doctors upped the dose. That led to a devastating addiction that took her years to overcome.

"I became an addict without knowing," Casey says.

David Tonkin blames his son's death from prescription opioids on a system that allowed him to see 24 doctors and get 23 different medications from 16 pharmacies—all in the space of six months. Between January and July 2014 alone, Matthew Tonkin got 27 prescriptions just for oxycodone.

Matthew's doctors were largely oblivious to what he was doing because Australia has no national, real-time prescription tracking system.

Coroners nationwide have long urged officials to create such a system. But the idea has been mired in bureaucratic delays.

Australia's government insists it is now taking the problem seriously. The opioid codeine, once available over the counter, was restricted to prescription-only in 2018. And last month, the country's drug regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, announced tougher opioid regulations, including restricting the use of fentanyl patches to patients with cancer, in palliative care, or under "exceptional circumstances."

"I can't speak for the past," says Greg Hunt, who became the federal Health Minister in 2017. "I can speak for my watch and my time where this has been one of my absolute priorities, which is why we've taken such strong steps. ... My focus has been to make sure that we don't have an American-style crisis."

-

Carmall Casey washes pills from an old pack of tapentadol down the sink while going through her box of medicine in her kitchen in Black River, Tasmania, Australia, Wednesday, July 24, 2019. She thought she had thrown all her opioids away. Casey's tried to quit in the past, returning drugs to pharmacies and dumping them down the sink. But eventually, the pain would grow unbearable, so she'd take the drugs again. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Carmall Casey finds an old pack of tapentadol while going through her box of medicine in her kitchen in Black River, Tasmania, Australia, Wednesday, July 24, 2019. Ten years ago, while working as a dairy farmer, Casey jumped off a truck and injured her knees. An operation provided temporary relief, but the pain came back. A doctor prescribed her opioids to ease her pain. When she stuck the first patch on her skin, it felt like heaven. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Shops line a street in the town of Stanley as a patron sips a cup of coffee in Tasmania, Australia, Tuesday, July 23, 2019. Like America's Appalachia, Tasmania is the country's epicenter for opioids. It has the nation's highest rate of opioid packs sold per person—2.7 packs each. One region has the highest number of government-subsidized opioid prescriptions in Australia: more than 110,000 for every 100,000 people. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Carmall Casey, right, sits with her son Joe, 15, before he leaves for school from their home in Black River, Tasmania, Australia, Wednesday, July 24, 2019. Casey admits now she made bad choices on the drugs. Choices that impacted her relationship with her kids. Relationships she's trying to mend. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Carmall Casey walks past photos of her kids that hang next to a clock in the shape of Tasmania, in her home in Black River, Tasmania, Australia, Tuesday, July 23, 2019. While struggling with her addiction, Casey lost her farm. Even worse, she says, she lost her daughter. She made bad choices on the drugs, she admits now. She was living with a volatile man who began to bully Sarah, so she sent her daughter, then 14, to live with her father. It's a decision that tore them apart, and still tears Casey apart today. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

CORRECTS LAST NAME - Joe Watkins, 15, waits with his dog, Ellie, for the school bus near his home in Black River, Tasmania, Australia, Wednesday, July 24, 2019. Watkins' mother was a dairy farmer when her drug addiction all began, a cheerful woman who loved taking Joe fishing and watching her daughter, Sarah, ride horses. And then one day, ten years ago, she jumped off a truck and felt her knees give way. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

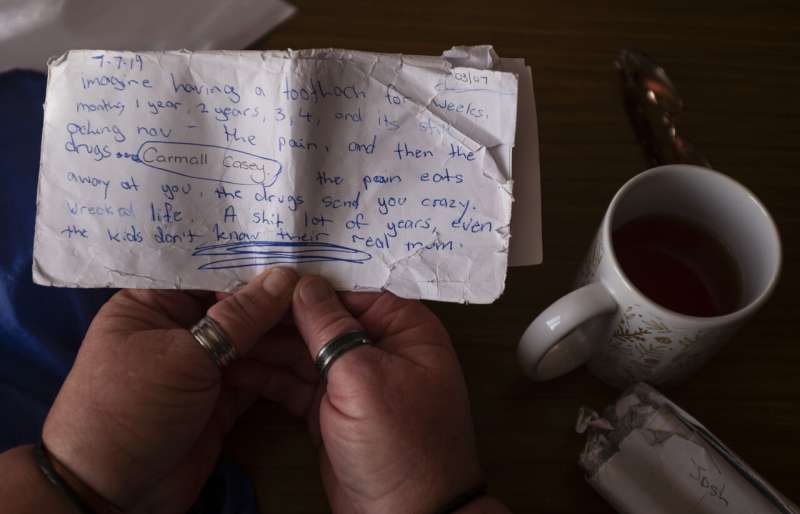

Joe Watkins, 15, boards his school bus as his dog, Ellie, stands by the door near their home in Black River, Tasmania, Australia, Wednesday, July 24, 2019. One day, Watkins' mom scrawled her anguish on a tattered envelope. "Imagine having a toothache for weeks, months 1 year, 2 years, 3, 4, and it's still aching now ... the pain eats away at you, the drugs send you crazy," she wrote. "Even the kids don't know their real mum." (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

With her favorite tree in the background, Carmall Casey stands for a photo on her front porch in Black River, Tasmania, Australia, Wednesday, July 24, 2019. The tree is dead and gnarled, but still standing. Like her, she says, it's old and broken, but still good for something. "But dead trees, even though they're dead, they've still got beauty of some kind haven't they?" (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Carmall Casey walks with her dogs on the beach in Hellyer, Tasmania, Australia, Wednesday, July 24, 2019. "It's like freedom when I'm on the beach," said Casey. "I look at the footprints and different shells and it helps to release all my stress and worries." (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

David Tonkin looks over the coroner report on his son, Matthew, as Matthew's friend, Ivo Kinshela, looks on in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. Kinshela considers David a father figure. He has long been close to the Tonkin family having lived with David and Matthew for three years when he was younger. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Ivo Kinshela wipes a tear while talking about his childhood friend, Matthew Tonkin, at the Tonkin's home in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. "Matt left Perth and Australia to Afghanistan a very healthy, fit young man, and he came back broken," said Kinshela. "And he came back broken and addicted to opioids." (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

David Tonkin holds a photo of his late son, Matthew, in his room at their home in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. The addiction that ultimately ended Matthew's life began in 2012, after he was injured during a training session while serving with the Australian army in Afghanistan. The pills had been prescribed to him by American doctors in Afghanistan. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Dr. Jennifer Stevens, a pain specialist, talks with patient Cheryl Rowley who is awaiting surgery at St. Vincent's Hospital in Sydney, Australia, Wednesday, July 17, 2019. "We were just pumping this stuff out into our local community, thinking that that had no consequences," says Stevens, a vocal advocate for changing opioid prescribing practices. "And now, of course, we realize that it does have huge consequences." (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

Bracelets remembering Matthew Tonkin, left, and his friend and fellow soldier, Robert Poate, sit on a table at the Tonkin home in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. Matthew was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, a result of the horrors he experienced in Afghanistan, including the death of his best friend, Poate. He was also suffering from a growing addiction to opioids. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

David Tonkin sits in his kitchen at his home in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. Tonkin blames his son's death on a system that allowed him to see 24 different doctors and get 23 different medications from 16 different pharmacies—all in the space of six months. Between January and July 2014 alone, Matthew Tonkin got 27 prescriptions just for oxycodone. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

David Tonkin walks past a mural decorated with the map of Australia and the word "Hope," in his neighborhood in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. His son, Matthew, who died from a drug overdose, hopped from clinic to clinic, collecting prescriptions for opioids and benzodiazepines, used to treat anxiety. The doctors were largely oblivious to what he was doing because Australia has no national, real-time prescription tracking system. (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

An empty pier stands at the park Matthew Tonkin used to play in as a child near his home and where he would routinely visit as an adult before his death at 24 from an opioid overdose in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. "We can't just wait nine years or nine more years to put in place some of these checks and the system. We need change now," said Ivo Kinshela, Matthew's childhood friend. "Because one more loss of life is too much. We need to act and we need to learn from his story." (AP Photo/David Goldman) -

David Tonkin pets Ned, his son Matthew's cat, that now sleeps on David's bed on the sleeping bag Matthew used in Afghanistan, in Perth, Australia, Sunday, July 21, 2019. After Matthew died, and for years to come, David would suddenly awaken at 10 p.m.—the same time that Matthew used to call from Afghanistan. Now, instead of Matthew's voice, there is only silence. Just like the silence from the officials he believes did little to prevent the death of his son. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

But for Sue Fisher, whose 21-year-old son Matthew died in 2010 of an overdose, it's too little, too late. The crisis is here, along with what she calls a "crisis of ignorance."

"Why aren't we learning from America's mistakes?" she says. "Why don't we learn?"

© 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.