Developing drugs to help fight Rift Valley fever virus

Research by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) scientists suggests that immune responses could be bolstered by drugs to help people recover from brain infections caused by an emerging pathogen.

The emerging pathogen studied by the team, known as Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV), is a disease that, to date, has been limited to outbreaks in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

But, as LLNL biologist and team leader Dina Weilhammer points out, "The reason we're concerned about it is because, like the West Nile virus, the Rift Valley fever virus also could spread to North America from Africa."

A paper about the team's research has been published in the PLOS Pathogens.

"Fundamentally, we were trying to understand how the immune response in the brain controls infections with Rift Valley fever virus. It's a mosquito-borne disease that can infect many types of livestock and people," Weilhammer said.

RVFV is a highly pathogenic virus capable of causing hepatitis, encephalitis, blindness, hemorrhagic syndrome and death in humans and livestock. It is most commonly seen in domesticated animals, such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats and camels. Upon aerosol infection with RVFV, there is an increased incidence of viral replication and tissue damage in the brain.

RVFV is classified as a category A biodefense pathogen by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases due to its potential to be aerosolized as a bioterrorist agent. The disease was first reported among livestock in the Rift Valley of Kenya in the early 1900s; the virus was first isolated in 1931.

When the virus is contracted by mosquito bite, it usually produces flu-like symptoms and liver inflammation but rarely brain infection in humans. When the virus is released as an aerosol, brain infection occurs at a much higher incidence.

"Data from animal handlers who have usually been involved in butchering and who have been exposed to animals infected with RVFV, along with a handful of laboratory exposures, show a higher incidence of brain infections from aerosol exposure to the virus," Weilhammer said.

Mouse models have confirmed that what happens with the RVFV in humans also occurs in mice. Mice injected with the virus had, like humans, a low frequency of brain infections, while those exposed by aerosol, had a higher incidence of brain infections.

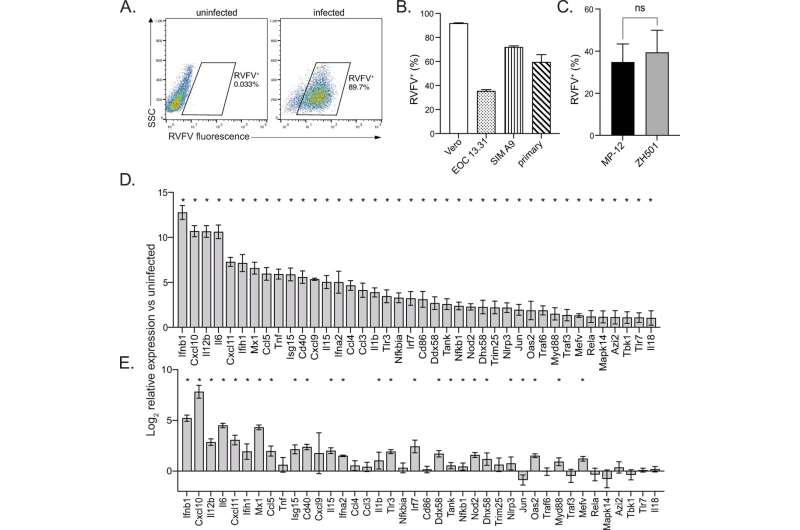

In their research with mouse models, the team found that the RVFV infects a special immune cell called microglia that exists only in the brains of people and mammals.

"We were surprised by the robust response of the microglia to the RVFV," Weilhammer said. "When the microglia are infected by the RVFV, these cells produced a robust type I interferon response, which is a first-line defense against viruses."

The LLNL scientists are the first researchers to discover the strong response of the microglia to a RVFV infection and also are the first researchers to find that when the brain is attacked by a RVFV infection, the body recruits natural killer cells to assist the microglia in fighting the infection.

"What we're thinking is: is there a way to help the natural killer cell response or the microglia with drugs be even better at controlling infections?" Weilhammer asked. "Our research suggests that there are immune responses that could be manipulated therapeutically to help people recover from brain infections.

"We've just scratched the surface learning about natural killer cells and the role they may play in fighting off RVFV infections in the brain. We need to understand more about how the natural killer cells get there and how they kill virally infected cells."

In their paper, the researchers wrote: "The results of this study provide a crucial step toward understanding the precise molecular mechanisms by which RVFV infection is controlled in the brain and will help inform the development of (improved) vaccines and antiviral therapies that are effective in preventing encephalitis."

More information: Nicholas R. Hum et al, MAVS mediates a protective immune response in the brain to Rift Valley fever virus, PLOS Pathogens (2022). DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010231