This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Image isn't everything: Research shows how the immediate environment may impact women's confidence

It's easy to celebrate female empowerment during Women's History Month, but promoting women's well-being beyond a few dedicated weeks is a different, more difficult story.

Researchers like UNM Psychology Professor Tania Reynolds are focusing on the reasons why, and by investigating how competition for romantic partners, and subtle cues of this competition, might influence women's confidence.

"Throughout history, women have been considered the more passive and less competitive sex. These stereotypes are oversimplified. It was obvious to me that women do compete," she said.

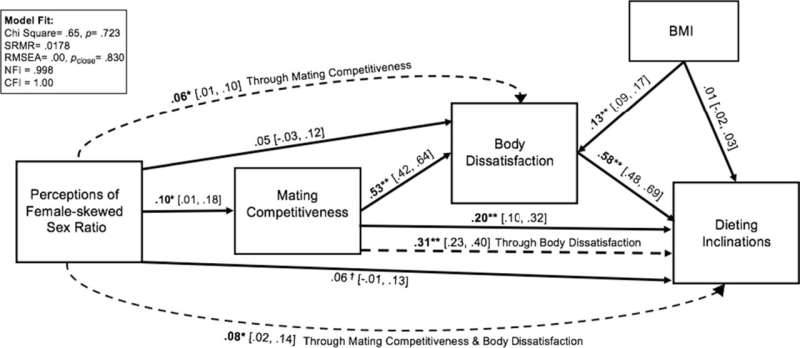

In the journal Archives of Sexual Behavior, Reynolds published the article "A Slim Majority: The Influence of Sex Ratio on Women's Body Dissatisfaction and Weight Loss Motivations." Through experiments and surveys with more than 1,700 women, the goal was to show how women's immediate environments influenced their body image and dieting motivations.

"From an evolutionary perspective, we are the descendants of ancestors who successfully competed for mates," Reynolds said. "Thus, on average, we should possess some of those same psychological tendencies to compare ourselves to same-sex peers and compete for mates. I am not sure that humans can ever totally rid themselves of these tendencies, if they are the tendencies that brought success for our ancestors."

The most important factor in affecting competition and self-image, Reynolds found, was something referred to as the sex ratio; that is the proportion of men to women in the local population.

"For those interested in opposite-sex romantic partners, the sex ratio reflects the degree of competition for romantic partners. That is, it reflects how many potential partners versus same-sex rivals are in the local environment. When the sex ratio is skewed towards more same-sex rivals, there is heightened competition for the limited pool of potential partners," Reynolds said.

"Although women do not often compete using physical blows, they are not the passive creatures society portrays them to me. Women compete for status, resources, information, and social partners. Across many species, females compete with one another. This competition becomes more intensified in female-skewed sex ratios, where there are fewer mates and more rivals. I wanted to see whether these patterns from the broader biological world also hold among humans, and they did," Reynolds said.

Reynolds discovered that women's immediate surroundings could influence their opinions of themselves and others. The more women relative to men in an area, the more competitive women felt with one another for romantic partners and the worse they felt about their bodies.

"When men were abundant, women felt more secure in their bodies and less motivated to lose weight. When men were relatively scarce, women felt more insecure about their bodies, because these environments are more competitive to attract or keep romantic partners," Reynolds said.

Aside from intensified pressures to compete for romantic partners, heterosexual women faced another battle when they returned home and looked in the mirror.

"We found that women who perceived themselves to be in a female-skewed sex ratio felt less satisfied with their bodies and more motivated to lose weight. These tendencies suggest that if women find themselves in contexts where there is a skew towards more women, they might experience body dissatisfaction and intensified dieting motivations," Reynolds said.

That skew in the sex ratio, with fewer men, and more women, led to women feeling worse about their appearances. These women were more dissatisfied with their bodies–their weight and shape–, and leaned more towards dieting. The opposite was true when the sex ratio favored men.

"When women find themselves in contexts where there are relatively more men, they might feel more satisfied with their bodies and less motivated to lose weight," Reynolds said.

That's something, Reynolds says, that women may want to consider when moving to new cities or selecting which colleges to attend.

"Our findings suggest that the environments women select into might have consequences for how they feel about their bodies. Thus, if one is choosing a city to move to, they might consider the sex ratios of those environments. If someone is very sensitive to self-other comparisons, they might feel happier in more male-skewed environments," she said.

Some real-life locations where there is a female skew in the sex ratio include big cities like New York City, Chicago, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. That's also a factor on college campus decisions, as the National Center of Education Statistics also shows college campuses are now skewed to be nearly 60% women.

"Our findings suggest women on college campuses might experience increased body dissatisfaction as a result of these skewed sex ratios. Thus, in these universities and large cities, women may find themselves surrounded by same-sex peers, struggling to find partners, and potentially, dissatisfied with their appearances," Reynolds said.

This study establishes another realm of concern when it comes to the oftentimes dangerous perceptions women have about themselves. The National Organization for Women reports a majority of women 59% reported dissatisfaction with their body shape, and 66% expressed the desire to lose weight. Reynolds' findings suggest the competitiveness of women's environments may play a role in the prevalence of these concerns.

However, Reynolds provided suggestions for how women might overcome some of these pressures.

"Another point worth considering is which type of partner we want to attract. Do we really want the partner who is so easily swayed by looks? If not, then maybe we should consider whom we are attracting by investing so much in our appearances. Maybe if we seek out traits in potential partners that go beyond the surface, such as intelligence or kindness, we will find partners who do the same" Reynolds said.

These concerns emerge early in women's lives too. As 50% of teens are self-conscious about their bodies, by age 60, 32.6% of women feel self-conscious about their bodies. These numbers do not consider the role of the sex ratio. It's important to note, however, Reynolds says, the social expectations around women's bodies fluctuate over time.

"What constitutes an idealized female body has changed over time and as we have become more food-secure. For example, some research finds that when people do not have reliable access to food, they are more attractive to heavier-set women," she said. "Thus, although humans might have mental adaptations to compare ourselves to one another, which body types are considered ideal have and will likely continue to change over time."

It's not an easy fix to simply not compare yourself to others; sex ratio aside, a startling 90% of women already compare their appearances to others on social media. Still, being aware of the sex ratio, and why you may feel this overwhelming self-deprecation is a start.

"Although women still face a lot of pressure to attract and retain romantic partners, it is worth considering whether that is an immediate priority for one's goals. Perhaps we can spend some time investing instead in our other goals," Reynolds said. "Some of the best predictors of life happiness are finding meaning or purpose and having fulfilling social relationships. Thus, one way to avoid the stress of romantic competition is to focus on the other areas of life that tend to lead to well-being."

Reynolds also says that if you're finding yourself critiquing, judging, or being hard on your appearance when it comes to looking for a partner, the age old adage of "looks aren't everything" still stands.

"If one finds themselves in a female-skewed environment, they might want to keep in mind that physical appearance is only one aspect of what makes someone attractive to potential romantic partners. Cross-cultural data suggest individuals also highly value intelligence, humor, honesty, kindness, communication skills, and dependability when selecting long-term romantic partners. Thus, there are many routes to increasing one's appeal to potential partners in these highly competitive environments."

It's also important to remember, especially during Women's History Month, that heterosexual women have shown time and time again that women can triumph and find fulfillment independent of men.

"Throughout human history, women were more dependent upon men to provide for themselves and their children," Reynolds said. "This is less true today when women have greater access to education, jobs, resources, and social support. Today, we have many more routes to status and security than by our romantic partners alone."

More information: Tania A. Reynolds et al, A Slim Majority: The Influence of Sex Ratio on Women's Body Dissatisfaction and Weight Loss Motivations, Archives of Sexual Behavior (2023). DOI: 10.1007/s10508-023-02644-0