Don't count on oxygen causing lung cancer

What causes cancer – and what can be done to prevent it – is one of the biggest questions in research – and although we've come a long way to answering it, there's always more to learn.

So when we see new research on the subject we sit up and pay attention.

But not all research is of the same standing. While some studies are so significant they can't be ignored, others give the merest hint of an effect and need further confirmation. And others… well, let's just call them 'less than robust'.

So which category do today's headlines about oxygen 'being linked to lung cancer' fall in to? (You can probably guess).

Lung cancer is the world's biggest cancer killer, and UK survival is low. But the disease is one of our big priorities – so new research helping us understand the risks surrounding it sounds like the sort of news we would be welcoming.

But the new research released yesterday – covered here in the Mail Online and the Mirror – hasn't quite got us beside ourselves with excitement.

Going back to the source

The reports come from a study by US scientists looking at rates of cancer in different counties in west-coast American states. They analysed publicly available information on cancer rates (as reported by the US National Cancer Institute for each state), and compared it to the average elevation of states (i.e. how high they are above sea-level) – to see if there was any link between a state's elevation and its incidence rate of four types of cancer – prostate, breast, colorectal and lung.

Looking at the patterns in the resulting data, the researchers concluded that there were fewer cases of lung cancer among populations who lived at higher elevations.

But then they went a step too far, given the limitations of their study (which we'll discuss below):

"Overall, our findings suggest the presence of an inhaled carcinogen inherently and inversely tied to elevation, offering epidemiological support for oxygen-driven tumorigenesis," they wrote.

Ecological studies

To understand why we think this is a bit over the top, let's consider the nature of the study.

The paper is a specific type of scientific study known as an ecological study – one that looks at data on whole populations rather than individuals.

Ecological studies can be useful; compared to things like randomised trials, they're usually quicker and cheaper because they often analyse data that is already available. This makes them a good way to get a broad look at potential relationships between suspected risk factors and a disease.

So, ecological studies are great for generating ideas that are potentially interesting but they often need further testing.

They also have particular limits and drawbacks, and in the case of ecological studies and causes of cancer there are a few serious limitations – limitations that turn into fatal flaws in the study we're discussing here.

Groups not individuals

Although such studies use data for a group overall, there is no way of assigning particular outcomes (say developing cancer) to individual people within the study.

For example, the data might show how many people in a group smoke, and how many people develop lung cancer – but they don't show that the smokers and lung cancer patients are necessarily the same people.

This is a big problem as, while they might give interesting results that suggest a link, they can't prove that link exists.

And because there's no data on each individual (for example, their age, sex, or medical history) other finer points are often lost in ecological studies. In this study, some of the risk factors known to influence the likelihood of developing lung cancer – like family history and occupational exposures to certain chemicals – aren't properly accounted and controlled for. (Although the new study did try to account for smoking by looking at average rates in each state – yet even this, as we'll see below, has problems).

One moment in time

Ecological studies use data from the past. So they also only give us a snap-shot of one point in time.

But diseases like cancer can take decades to develop, so while a snapshot can be a useful starting point, it doesn't allow for things changing over time – like people moving to live in different areas, quitting or taking up smoking, or anything else that can have a bearing on cancer risk.

So what about oxygen and cancer?

In this particular study, one of the biggest problems is that, because lung cancer takes many decades to develop, the two sets of data they used aren't really comparable.

For instance, the smoking rate data that the researchers use to account for the effects of smoking is from 1997-2003. But the figures for lung cancer incidence are from less than a decade later: 2005-2009.

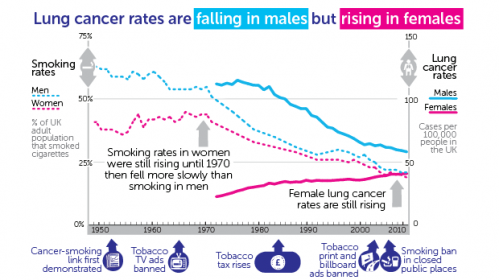

This is a real problem, because to accurately calculate how many of the cases of lung cancer are due to smoking you need to use data from 30 -40 years ago. (You can see the time lag in the graph below).

This doesn't just mean the proportion of cases of lung cancer in the study linked to smoking is inaccurate. It also leaves a gap in the data through which overinterpretation and exaggeration can slip in: cases that could really be due to smoking become attributed to other, unknown and mysterious risk factors.

Such as, say, a mythical "inhaled carcinogen inherently and inversely tied to elevation".

The gold standard

So we hope that, given the above limitations, you're reassured that you're not increasing your cancer risk by simply breathing. From what we can tell, it's likely that the 'link' found in this paper, between altitude and lung cancer, is simply due to the failure to take smoking fully into account.

But at this point it may be sounding like we're impossible to please, so what is it that we look for when we're examining scientific evidence? Why do we pour scorn on this study, but accept others as sufficient evidence around which to base awareness campaigns and lifestyle advice?

Here's a quick bluffers' guide:

Accounting for other factors: cancer risk is complex, and there are many factors at play. Checking that any results are down to the one factor that is being looked at requires properly taking into account all the other factors known to have an impact on cancer risk, like lifestyle choices, age, gender etc.

Large numbers: studying larger groups of individuals makes statistics more powerful – we can be more confident that the results aren't just down to chance.

Un-biased: when conducting research it can be hard to account for small potential biases – e.g. which groups are included in the research, what details a participant might be more or less likely to recall. Using a prospective design – starting with healthy people, learning about their lifestyle and seeing who develops cancer and who doesn't helps avoid this.

Consistency: being able to reproduce the results of a study is a cornerstone of scientific research, and studying populations is no different to cells in a lab – studies that agree and build up to form a body of evidence are much more convincing.

Biological plausibility: conclusions which fit with our knowledge and understanding of the world and its underlying biology are always far more convincing than, say, studies that need to call into existence an "inhaled carcinogen inherently and inversely tied to elevation".

So, in summary: this paper is an interesting read certainly, but definitely doesn't tell us that oxygen causes lung cancer.

More information: Simeonov, K., & Himmelstein, D. (2015). "Lung cancer incidence decreases with elevation: evidence for oxygen as an inhaled carcinogen" PeerJ, 2 DOI: 10.7717/peerj.705