Research reveals new aspect of platelet behavior in heart attacks: Clots can sense blood flow

The disease atherosclerosis involves the build up of fatty tissue within arterial walls, creating unstable structures known as plaques. These plaques grow until they burst, rupturing the wall and causing the formation of a blood clot within the artery. These clots also grow until they block blood flow; in the case of the coronary artery, this can cause a heart attack.

New research from the University of Pennsylvania has shown that clots forming under arterial-flow conditions have an unexpected ability to sense the surrounding blood moving over it. If the flow stops, the clot senses the decrease in flow and this triggers a contraction similar to that of a muscle. The contraction squeezes out water, making the clot denser.

Better understanding of the clotting dynamics that occur in atherosclerosis, as opposed to the dynamics at play in closing a wound, could lead to more effective drugs for heart-attack prevention.

The research was conducted by graduate student Ryan Muthard and Scott Diamond, professor and chair of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

Their work was published in the journal Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, which is published by the American Heart Association.

"Researchers have known for decades that blood sitting in a test tube will clot and then contract to squeeze out water," Muthard said. "Yet clots observed inside injured mouse blood vessels don't display much contractile activity. We never knew how to reconcile these two studies, until an unexpected observation in the lab."

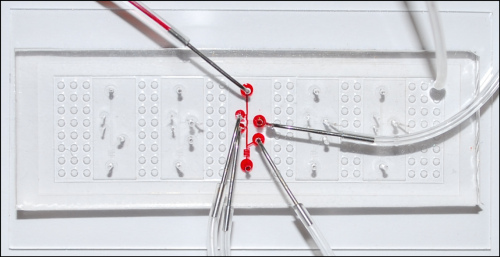

Using a specially designed microfluidic device, the researchers pulsed fluorescent dye across a clot to investigate how well it blocked bleeding. When they stopped the flow in order to adjust a valve to deliver the dye, the researchers were startled to see that a massive contraction was triggered in the clot. If they delivered the dye without stopping flow, there was no change in the clot properties.

"We think this may be one of the fundamental differences between clots formed inside blood vessels that cause thrombosis and clots formed when blood slowly pools around a leaking blood vessel during a bleeding event," Diamond said. "The flow sensing alters the clot mechanics."

To investigate this alteration, the researchers used an intracellular fluorescent dye that binds to calcium. They found that when the flow stops, the platelets' calcium levels increase and they become activated. By adding drugs that block ADP and thromboxane, chemicals involved in the clotting process, the researchers were able to prevent this platelet calcium mobilization and stop the contraction.

Millions of patients already take drugs that target these chemical pathways: P2Y12 inhibitors, such as Plavix, block ADP signaling in platelets, and aspirin blocks platelets' synthesis of thromboxane. This discovery suggests that these drugs may be interfering with contractile mechanisms that are triggered when ADP and thromboxane become elevated, such as when the flow around the clot decreases or stops. Beyond slowing the growth of clots, these anti-platelet drugs may also be altering the mechanics of the clot by preventing contraction.

"It is an example of 'quorum sensing' by the platelets in the clots," Diamond said. "The platelets are sensing each other and the prevailing environment. This causes them to release ADP and thromboxane, but it is rapidly diluted away by the surrounding blood flow.

"However, when the flow over the clot decreases or stops, the ADP and thromboxane levels rapidly build up, and this drives platelet contraction," Diamond said.

More information: atvb.ahajournals.org/content/e … 75-adab-e9be5b4ba202