Uncovering how humans hear one voice among many

Humans have an uncanny ability to zero in on a single voice, even amid the cacophony of voices found in a crowded party or other large gathering of people. Researchers have long sought to identify the precise mechanisms by which our brains enable this remarkable selectivity in sound processing known as the "cocktail party effect."

In a new study published in the journal Neuron, University of Maryland Associate Professor Jonathan Simon (Biology/Electrical and Computer Engineering), recent Maryland Ph.D. graduate Nai Ding, lead author Elana M. Zion Golumbic of Columbia University and colleagues from Columbia and other New York universities at last are unlocking these neural mechanisms, using data recorded directly from the surface of the brain.

In a crowded place, sounds from different talkers enter our ears mixed together, so our brains first must separate them using cues like when and from where the sounds are coming. But we also have the ability to then track a particular voice, which comes to dominates our attention and later, our memory. One major theory hypothesizes we can do this because our brains are able to lock on to patterns we expect to hear in speech at designated times, such as syllables and phrases in sentences. The theory predicts that in a situation with competing sounds, when we train our focus exclusively on one person, that person's speech will dominate our brain's information processing.

Of course, inside our brains, this focusing and processing takes the form of electrical signals racing around a complicated network of neurons in the auditory cortex.

To begin to unlock how the neurons figure things out, the researchers used a brain-signal recording device called electrocorticography (ECoG). These devices, implanted directly in the cortex of the brain, are used in epilepsy surgery. They consist of about 120 electrodes arranged in an array over the brain's lateral cortex.

With the permission of the surgery patients, researchers gave them a cocktail party-like comprehension task in which they watched a brief, 9-12 second movie of two simultaneous talkers, side by side. A cue in the movie indicated to which talker the person should try to listen. The ECoG recorded what was happening in the patients' brains as they focused on what one of the talkers was saying.

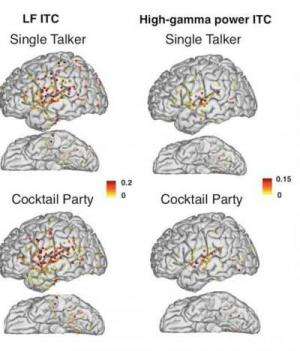

The researchers learned that low-frequency "phase entrainment" signals and high-frequency "power modulations" worked together in the brain to dynamically track the chosen talker. In and near low-level auditory cortices, attention enhances the tracking of speech we're paying attention to, while ignored speech is still heard. But in higher-order regions of the cortex, we become more "selective"—there is no detectable tracking of ignored speech. This selectivity seems to sharpen as a speaker's sentence unfolds.

"This new study reaffirms what we've already seen using magnetoencephalography (MEG)," says Simon, who holds a joint appointment in both the University of Maryland's A. James Clark School of Engineering and College of Computer, Mathematical and Natural Sciences. Simon's lab uses MEG, a common non-invasive neuroimaging method, to record from ordinary individuals instead of neurosurgery patients. "In fact, the methods of neural data analysis developed in my lab for analyzing MEG results proved to be fantastic for analyzing these new recordings taken directly from the brain."

"We're quite pleased to see both the low frequency and high frequency neural responses working together," says Simon, "since our earlier MEG results were only able to detect the low frequency components." Simon's own MEG research currently is investigating what happens when the brain is no longer able to pick out a talker from a noisy background due to the effects of aging or damaged hearing.

Simon also notes that the new study's results are in good agreement with the auditory theories of another University of Maryland researcher, Shihab Shamma (Electrical and Computer Engineering and Institute for Systems Research), Maryland alumna Mounya Elhilali (now on faculty at Johns Hopkins University), and their colleagues, who are part of a wide-ranging, collaborative family of neuroscience researchers originating at Maryland.

A better understanding of the cocktail party effect could eventually help those who have trouble deciphering a single voice in a noisy environment, such as some elderly and some people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. It might also lead to technology improvements such as cell phones that can block background voices to improve transmission quality of its user's voice.

The article is titled "Mechanisms Underlying Selective Neuronal Tracking of Attended Speech at a 'CockTail Party'."

More information: www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273(13)00045-7