Discovery sheds light on why Alzheimer's meds rarely help

New research reveals that the likely culprit behind Alzheimer's disease has a different molecular structure than current drugs' target—perhaps explaining why these medications produce little improvement in patients.

The Alzheimer's Association projects that the number of people living with Alzheimer's disease will soar from 5 million to 13.8 million by 2050 unless scientists develop new ways to stop the disease. Current medications do not treat Alzheimer's or stop it from progressing; they only temporarily lessen symptoms, such as memory loss and confusion.

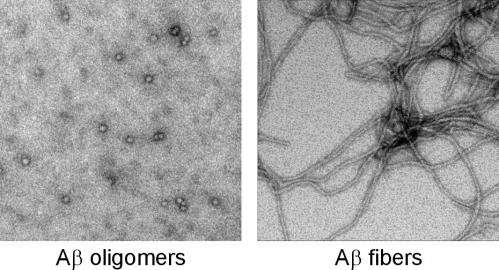

Current Alzheimer's drugs aim to reduce the amyloid plaques—sticky deposits that build up in the brain—that are a visual trademark of the disease. The plaques are made of long fibers of a protein called Amyloid ?, or A?. Recent studies, however, suggest that the real culprit behind Alzheimer's may be small A? clumps called oligomers that appear in the brain years before plaques develop.

In unraveling oligomers' molecular structure, UCLA scientists discovered that A? has a vastly different organization in oligomers than in amyloid plaques. Their finding could shed light on why Alzheimer's drugs designed to seek out amyloid plaques produce zero effect on oligomers.

The UCLA study suggests that recent experimental Alzheimer's drugs failed in clinical trials because they zero in on plaques and do not work on oligomers. Future studies on oligomers will help speed the development of new drugs specifically aiming at A? oligomers.

The study was published as Paper of the Week in the June 28 issue of the peer-reviewed Journal of Biological Chemistry.