World's oldest working scientist takes on Alzheimer's

Professor Fred Kummerow needs money. The bio-chemist at the University of Illinois wants to study the link between diet and Alzheimer's disease, and he won't find out until next spring if he won a three-year federal grant for his research lab.

He's asking for donations to keep the lab going. That's all he said he wanted for his 101st birthday.

Philanthropists might question the value of donating to the world's oldest working scientist. But even in his ninth decade of research, Kummerow knows he's a good investment:

"I've gotten the trans fat out of the diet - has somebody else done that?"

Trans fats are found in margarine, fried foods and processed foods such as crackers and snack cakes. After nearly 60 years of writing about the link between trans fats and heart disease, Kummerow was vindicated in 2013 when the Food and Drug Administration required food companies to phase out the fats. The ban came just months after Kummerow sued the agency for its failure to act on his findings.

"The industry is very powerful, and they love to have this stuff in the diet because it has a long shelf life," Kummerow said.

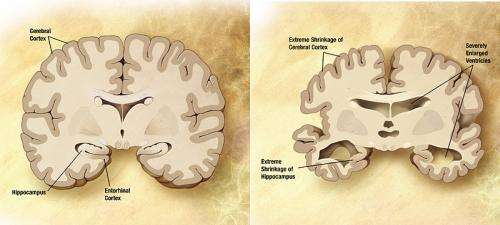

Now, Kummerow wants to show how a poor diet can cause brain plaques seen in dementia and Alzheimer's disease. It's a personal quest - his sister-in-law and benefactor Verna Hildebrand died of the disease last year. Kummerow studied the menus from her nursing home and was dismayed to find too many carbohydrates and a lack of eggs, vegetables and fruit in the residents' diets.

Kummerow recently applied to the National Institute on Aging for a $1.8 million, three-year grant to study the effects of diet on pigs' brains. The scientist and his team including two assistant professors in the university's College of Veterinary Medicine plan to feed three groups of pigs diets containing different amounts of fats. Then they'll check the animals' brains for the plaques and blockages that are linked to Alzheimer's. Kummerow is confident they'll find a connection.

"These oxidized fats get into the brain. And as I've been working for 60 years with fats and cholesterol, I thought I could make a contribution to Alzheimer's research," Kummerow said.

Although Kummerow technically retired from the university at 71, he never quit working. He rode a bike to his campus lab into his 80s. The lab, with two assistant professors who volunteer half their time, is funded from Kummerow's own money and donations from a couple of charitable foundations. His published scientific papers total 460.

"I've never relaxed in my life. I've always worked," Kummerow said. "When most people retire they may be good for a couple weeks or a couple months but eventually they don't use their brains enough and it's hard to get started on something. I want to do something that will contribute to the welfare of people."

Even Kummerow's vacations are work trips. He has traveled to 32 countries, including a trip behind the Iron Curtain in the 1970s. There he survived an earthquake in Romania that was 7.2 on the Richer scale that killed more than 1,500 people. On the same trip, American embassy staff told him his hotel room in Leningrad was bugged. But the only secrets Kummerow was after were scientific.

"I wanted to know if they knew any more about heart disease than we did. And they didn't. Nobody knew more than we did," he said.

Back in his lab, Kummerow set out to prove that cholesterol did not cause heart disease, a theory that contradicted the scientific consensus of the time. The professor picked apart the diseased arteries surgeons had removed during bypass surgeries. He compared those to the arteries of pigs who had no cholesterol in their diets but still had blockages. Kummerow concluded it had to be trans fats and oxidized fats, created from frying, that clogged up arteries. Dietitians started to agree. Today, the once-vilified egg with its bundle of cholesterol is considered a health food, just as Kummerow always claimed.

He still eats one egg every day for breakfast, along with oatmeal mixed with yogurt, one banana and three prunes. A caregiver-turned-research-assistant helps Kummerow with computer work and cooks his meals. Lunch is baked chicken or fish, steamed vegetables and a salad with orange juice and vinegar dressing. Dinner is the same as lunch, but with smaller portions. The professor drinks whole milk and never any alcohol. He rarely needs a nap. On occasion, he'll treat himself to a small slice of cherry pie. A nurse visits each Wednesday to check his blood pressure (good) and lungs (clear).

Kummerow's colleagues hope his next book will be an autobiography. But the professor says his work is more interesting than his life. Diana Yates, a health sciences writer at the university, calls Kummerow "an iconoclast."

"He's somehow managed to avoid adopting the common wisdom about big medical issues, choosing instead to see for himself - with fresh vision and original questions that nobody else has thought to ask," said Yates, a health sciences writer at the university.

On Oct. 4, his friends and family gathered to celebrate the professor's birthday with an angel food cake. It's fat-free.

©2015 St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.