Researchers find the key to loss of smell with Parkinson's disease

University of Auckland research has found an anatomical link for the loss of the sense of smell in Parkinson's disease.

The research, published in the journal Brain, is the work of academics Associate Professor Maurice Curtis, Dr Victor Dieriks, Dr Sheryl Tan and Sir Richard Faull. All are part of the Centre for Brain Research at the University's Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences.

They worked alongside academics Dr Peter Mombaerts and Dr Bolek Zapiec from the Max Planck Research Unit for Neurogenetics in Frankfurt, Germany. The work in New Zealand was funded by the Neuro Research Charitable Trust, founded by Bernie Crosby who himself has Parkinson's disease. The work in Germany was funded by the Max Planck Society.

Parkinson's disease is a progressive, degenerative disorder of the brain. Symptoms include tremors, stiffness or rigidity, and slowness of movement. According to Parkinson's New Zealand, approximately 1 percent of people over the age of 60 have the condition. There is no cure so treatment will normally focus on managing symptoms, typically with medication.

Loss of the sense of smell is an often overlooked but remarkably prevalent early symptom of Parkinson's disease.

"A complete loss of smell or a diminished sense of smell often precedes the usual motor symptoms of this neurodegenerative disease by several years, and has a prevalence of 90 per cent in early-stage patients," Associate Professor Curtis says.

The olfactory bulb is a part of the brain that acts as a primary relay station for smell signals from olfactory sensory neurons that detect smells in the nose. These neurons identify smells in the environment. Smell signals are transmitted via axons – the long thread-like part of a nerve cell - of the sensory neurons, which terminate and come together into thousands of structures called glomeruli. The odour-induced signals are processed in the olfactory bulb and relayed to several other parts of the brain including the olfactory cortex.

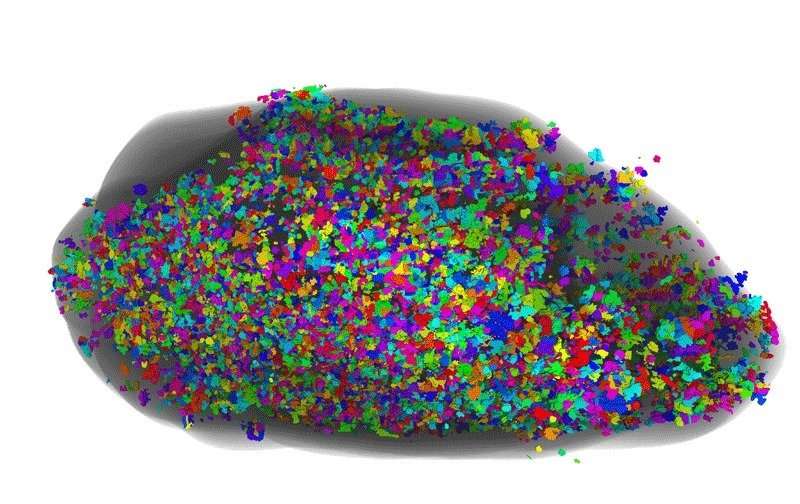

The researchers compared the olfactory bulbs from people with and without Parkinson's disease and found that the volume taken up by the glomeruli (the functional units of the olfactory bulb) was reduced by more than half in Parkinson's patients. The researchers discovered that the distribution of the glomeruli was greatly altered. The olfactory bulbs of normal cases had 70 per cent of their glomerular component in the bottom half of the olfactory bulb, but the olfactory bulbs of Parkinson's disease cases had only 44 per cent in the bottom half.

This reduction is consistent with the hypothesis that Parkinson's disease begins with bacteria, viruses or environmental toxins entering the brain via the nose and affecting first the olfactory bulb, where the neurodegenerative disease is triggered and gradually spreads through other parts of the brain.

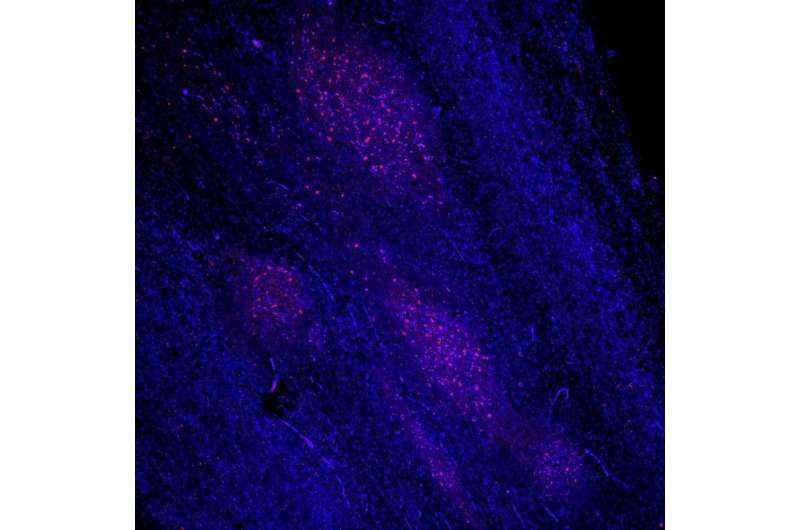

The New Zealand-based researchers were able to collect olfactory bulbs fit for an in-depth quantitative study. In a globe-spanning project, the researchers processed the post mortem olfactory bulbs, cut thousands of ten-micrometer thin sections throughout its entire length, and stained the sections with fluorescently labeled antibodies. The labeled sections were then scanned in Frankfurt, and the images reconstructed in 3-D allowing for quantitative whole-olfactory bulb analyses.

"The research has required painstaking attention to detail and collaboration on an international scale. The drive within our international team has been significant to see that this work was done to a high standard and that we used the generously gifted human brain tissue to gain the best results possible," Associate Professor Curtis says.

As glomeruli of the human olfactory bulb are difficult to count unambiguously, the researchers came up with a new, quantitative parameter: the global glomerular voxel volume. This quantity is the sum of the volume of all the glomeruli in the olfactory bulb. Having defined this new parameter, the researchers compared the values between olfactory bulbs from normal and Parkinson's disease cases, and found that it was reduced by more than half. Whether the decrease is the result of Parkinson's patients having fewer or smaller glomeruli, or is due to a combination of these two effects, remains to be seen.

The Neurological Foundation of New Zealand Douglas Human Brain Bank at the University of Auckland worked closely with families of patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases to ensure ethical and effective tissue collection of postmortem brain samples from people with Parkinson's disease, and people without.

This research will be followed up with further work to understand what causes the glomeruli to deteriorate in Parkinson's disease and to demonstrate what other changes occur in the olfactory bulb in Parkinson's disease. This work is already underway.

More information: Bolek Zapiec et al. A ventral glomerular deficit in Parkinson's disease revealed by whole olfactory bulb reconstruction, Brain (2017). DOI: 10.1093/brain/awx208