More patients cope with diagnosis of epilepsy

As he was growing up, Paul Shaffer sometimes froze in his tracks and felt like he was walking away from his body.

He did not tell anyone about the sensation, which usually passed quickly: "Who would believe me?"

It was not until he was in his 20s and convulsions knocked him out of his chair at work that a doctor told him he had epilepsy and he was having seizures. Still Shaffer, now 54, did not do anything about it until years later when he crashed his car and his wife insisted on a proper assessment and treatment.

It's not uncommon for epilepsy to go undiagnosed and untreated for years. Doctors don't always recognize it or don't want to don't label the condition. Because it can be stigmatized, patients don't always accept the diagnosis, even as the condition wreaks havoc on their lives.

But researchers are discovering that epilepsy affects far more people than ever thought. About 3.4 million Americans had epilepsy in 2015 - a 25 percent jump in about five years, according to a report released this month by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While the CDC could not fully explain the rise in cases, attributing it partly to population growth, officials at the Epilepsy Foundation and others say there is no doubt that the numbers reflect a far more thorough accounting of people with the condition.

"We don't have the equivalence of a pregnancy test, a yes or no," said Dr. Jennifer Hopp is a neurologist at the University of Maryland Medical Center who leads the center where Shaffer is being treated. "There is a comprehensive evaluation that needs to be done. And every patient is a little different."

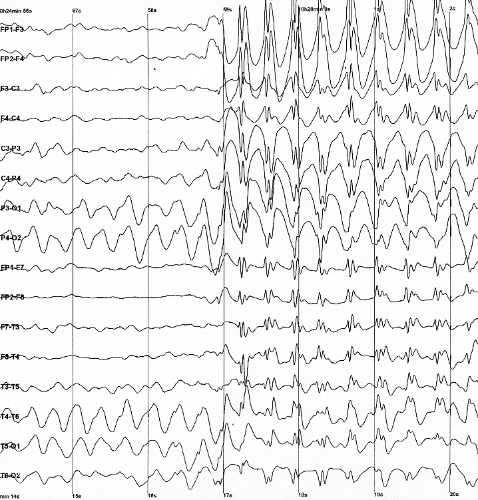

Epilepsy is a brain disorder that causes any kind of seizure, from convulsions to staring to confused behavior. The condition can stem from strokes, head injuries, infections or genetic mutations, and is diagnosed when someone has two unprovoked seizures or one seizure but is likely to have more.

Seizures often frighten sufferers and people who witness them, perpetuating the stigma, said Patricia Osborne Shafer, the Epilepsy Foundation's senior director of health information and resources and epilepsy clinical nurse specialist in Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center's Comprehensive Epilepsy Center in Boston.

"People fear the word epilepsy," said Shafer, who did not know until college that she had the condition because doctors only told her she had a seizure disorder, perhaps cutting her off from resources that were available. "This feeds into why people may not know or haven't been told they have it."

Experts, advocates and patients hope the greater number of cases brings attention and resources to people who often struggle with everything from relationships and parenting to working and driving.

"Epilepsy is common, complex to live with, and costly," said Rosemarie Kobau, head of CDC's Epilepsy Program, when the agency report was released. "It can lead to early death if not appropriately treated."

Many people take years to get to a neurologist trained in epilepsy, who not only can diagnose the condition but steer patients to the best therapies.

Patients can be treated with one or more medications, surgery to remove brain tissue where abnormal activity occurs or implantable devices to help control seizures.

Shaffer now takes 14 medications a day, though some are for other medical conditions than epilepsy. His main goals are to better control his seizures, which he had been experiencing three or four times a month, and to get off the drugs that can be tough to manage and make him feel sick.

He wasn't a good candidate for surgery, which can offer immediate relief because the problem area is removed, because his seizures stemmed from both sides of his brain, said Hopp, also an associate professor of neurology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

So he became one of her first patients to get an implanted device. The responsive neurostimulation device, approved just a few years ago by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, constantly monitors brain activity and is programmed to detect specific patterns that can lead to a seizure. The thumb-size device sends brief electric pulses that disrupt abnormal activity before a seizure begins.

It's the latest technology, giving doctors another option for treatment when medications are not effective. Only about 60 percent of patients get a good response from epilepsy drugs.

During a recent visit to Hopp, scans showed Shaffer had no seizures for seven weeks, though he experienced a set only the day before the appointment.

"That shows it's working," said Hopp, who along with Jordan Takas, a therapy consultant from the device manufacturer NeuroPace, set the computer to give Shaffer bigger jolts in an effort to stop more seizures.

Shaffer said he knows the seizures upset his family, a burden for a doting dad who made sure everyone during his latest doctor's visit knew his 17-year-old daughter Josie Shaffer had just been appointed as a student member of the Baltimore County Board of Education.

For her part, Josie said she did not mind driving him to doctor appointments and elsewhere, though she did not much like navigating Baltimore City streets. She said the condition does bother her and her 15-year-old sister, as well as their mother, who often sends them out of the room or to walk the dog when their father has seizures.

"I hope this helps him," she said of the new device, implanted in February.

Up to 85 percent of patients eventually have improvements with the technology, including one patient who Takas said has been seizure free for seven years and others who have been able return to driving. In Maryland, patients have to show they have been seizure free for 90 days to apply for a driver's license.

No seizures is everyone's goal, Hopp said. Seizures can lead to injuries from falls, drowning in a tub, accidents while cooking or driving. The condition is linked to depression, and, rarely, it can cause patients to die in their sleep.

Hopp said developing treatment plans is highly individual, taking into account what would work best to control seizures and any life plans, such as child-bearing or other medical conditions.

"It's important to take a medical history, but it's really important to listen to them and their goals," Hopp said. "We take a lot of time on this. ... We focus on the best quality of life for a patient."

The Epilepsy Foundation's Shafer said depression and anxiety are concerns for many epilepsy patients that also need to be addressed by professionals. Some need legal aid, such as patients who fear losing custody of children or jobs.

The public also needs education about responding to seizures, she said. (The quick first aid to keep people safe: Sit them down or lie them on their side, protect their head, don't restrain them and call 911 only if the seizure lasts more than about three minutes.)

She said people with epilepsy can feel a loss of control, or like "they have a time bomb in the head."

New patients want quick answers about how they can be treated and how it will affect their lives, Shafer said. But it's really more of a "journey," with people having to understand what triggers their seizures or what works to control them and how it all affects their ability to go about daily activities.

"Sometimes we can answer questions and sometimes we can't," she said. "They need to understand what they have and what it means to them on a personal level and on a treatment level. ... Knowing how many people are affected is a start."

©2017 The Baltimore Sun

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.