Movement toward a poop test for liver cirrhosis

For the estimated 100 million U.S. adults and children living with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), whether or not they have liver cirrhosis, or scarring, is an important predictor for survival. Yet it's difficult and invasive to detect liver cirrhosis before it is well advanced. In an effort to quickly and easily identify people at high risk for NAFLD-cirrhosis, researchers in the NAFLD Research Center and Center for Microbiome Innovation at University of California San Diego identified unique patterns of bacterial species in the stool of people with the condition.

The study publishes March 29, 2019 in Nature Communications.

"If we are better able to diagnose NAFLD-related cirrhosis, we will be better at enrolling the right types of patients in clinical trials, and ultimately will be better equipped to prevent and treat it," said senior author Rohit Loomba, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at UC San Diego School of Medicine, director of the NAFLD Research Center and a faculty member in the Center for Microbiome Innovation at UC San Diego. "This latest advance toward a noninvasive stool test for NAFLD-cirrhosis may also help pave the way for other microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics, and better enable us to provide personalized, or precision, medicine for a number of conditions."

The precise cause of NAFLD is unknown, but both diet and genetics play substantial roles. Up to 50 percent of obese people are believed to have NAFLD, and people with a first-degree relative with NAFLD are at increased risk for the disease themselves.

In a previous proof-of-concept study of patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD, Loomba and colleagues found a gut microbiome pattern that distinguished mild/moderate NAFLD from advanced disease, allowing them to predict which patients had advanced disease with high accuracy. In this latest study, Loomba's team wanted to know if a similar stool-based "read-out" of what is living in a person with NAFLD's gut might provide insight into his or her cirrhosis status.

The researchers analyzed the microbial makeup of stool samples from 98 people known to have some form of NAFLD and 105 of their first-degree relatives, including some twins. They did this by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene, a genetic marker specific for bacteria and their relatives, archaea. The 16S rRNA sequences serve as "barcodes" to identify different types of bacteria and the relative amounts of each, even in a mixed sample like stool.

The researchers first noticed that people who share a home also tended to share similar microbial patterns in their gut microbiomes, further validating several previous studies. In addition, they observed that people with extreme forms of NAFLD had less diverse and less stable gut microbiomes.

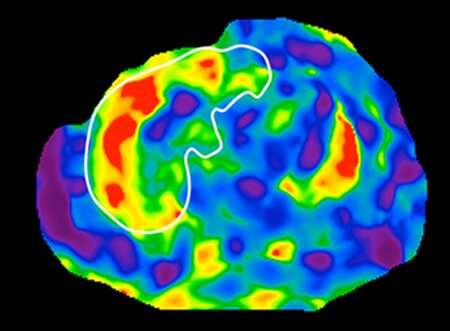

Then the team identified 27 unique bacterial features unique to the gut microbiomes, and thus stool, of people with NAFLD-cirrhosis. The researchers were able to use this noninvasive stool test to pick out the people with known NAFLD-cirrhosis with 92 percent accuracy. But more importantly, the test allowed them to differentiate the first-degree relative with previously undiagnosed NAFLD-cirrhosis with 87 percent accuracy. The results were confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

While Loomba estimates that a stool-based microbiome diagnostic might cost $1,500 if it were on the market today, he predicts that cost will lower to less than $400 in the next five years due to advances in genomic sequencing and analysis technologies.

The researchers caution that so far this new diagnostic approach has only been tested in a relatively small patient group at a single, highly specialized medical center. Even if successful, a stool-based test for NAFLD wouldn't be available to patients for at least five years, they said. Loomba also pointed out that while a distinct set of microbial species may be associated with advanced NAFLD-cirrhosis, this study does not suggest that the presence or absence of these microbes causes NAFLD-cirrhosis or vice versa.

More information: DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9Nature Communications (2019).