Peru's Indigenous turn to ancestral remedies to fight virus

As COVID-19 spread quickly through Peru's Amazon, the Indigenous Shipibo community decided to turn to the wisdom of their ancestors.

Hospitals were far away, short on doctors and running out of beds. Even if they could get in, many of the ill were too fearful to go, convinced that stepping foot in a hospital would only lead to death.

So Mery Fasabi gathered herbs, steeped them in boiling water and instructed her loved ones to breathe in the vapors. She also made syrups of onion and ginger to help clear congested airways.

"We had knowledge about these plants, but we didn't know if they'd really help treat COVID," the teacher said. "With the pandemic we are discovering new things."

The coronavirus pandemic's ruthless march through Peru—the country with the world's highest per-population confirmed COVID-19 mortality rate—has compelled many Indigenous groups to find their own remedies. Decades of under-investment in public health care, combined with skepticism of modern medicine, mean many are not getting standard treatments like oxygen therapy to treat severe virus cases.

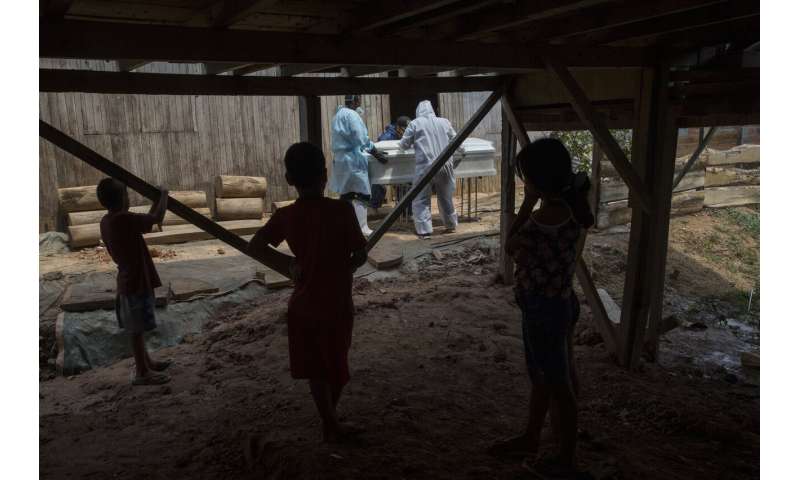

In the Ucayali region, government rapid response teams deployed to a handful of Indigenous communities have found infection rates as high as 80% through antibody testing. Food and medicine donations have reached only a fraction of the population. Many say the only state presence they have seen is from a group responsible for collecting bodies of the dead.

At a spot known as "Kilometer 20" near the city of Pucallpa, a new cemetery has sprung to life with the remains of about 400 people.

"We've always been forgotten," said Roberto Wikleff, 49, a Shipibo man who turned to Fasabi's treatments to help treat his COVID-19. "We don't exist for them."

Peru is home to one of Latin America's largest Indigenous populations, whose ancestors lived in the Andean country before the arrival of Spanish colonists. Entire tribes were wiped out by infectious diseases introduced by the Europeans. Today many live and work in urban areas, but others reside in remote parts of the Amazon that have few doctors, let alone the capacity to do complex molecular testing or treatment for the virus.

Wikleff said the 10 doctors, nurses and aides who usually staff a nearby clinic abandoned their posts when the coronavirus arrived. The Shipibo had tried to prevent COVID-19's entrance by blocking roads and isolating themselves. But in May, he and others nonetheless came down with fevers, coughs, difficulty breathing and headaches.

A month later, he was still feeling ill and turned to Fasabi, who along with 15 other volunteers had set up a makeshift treatment center.

"I was taken there in agony," he recalled.

The Shipibo highlight the use of a plant known locally as "matico." The buddleja globosa plant has green leaves and a tangerine-colored flower. Fasabi said that by no means are the remedies a cure, but their holistic approach is proving effective. Unlike in hospitals, volunteers equipped in masks get close to patients, giving them words of encouragement and touching them through massage.

"We are giving tranquility to our patients," she said.

Juan Carlos Salas, director of Ucayali's regional health agency, said efforts to expand hospital capacity have proven only marginally successful. The region of about a half million people located along a winding river had just 18 ICU beds at the start of the pandemic and today has around 28. A shortage of specialists means they have not been able to staff all the beds.

At the peak of the outbreak in May and June, around 15 people were dying a day, he said. Overall, about 14,000 cases have been diagnosed, likely a vast undercount.

"We didn't have a way of tending to patients," he said. "We couldn't accept more."

He said transportation is one of the biggest hurdles in treating Indigenous groups, some of which can only be reached by helicopter or an eight-hour boat ride. Pucallpa's bustling port where wood, bananas and other fruit are loaded onto ships for export is believed to be one main source of contagion.

Of about 59,000 rapid antibody tests, some 2,500 were administered to Indigenous groups.

"We were surprised," Salas said. "The majority had been infected."

Lizardo Cauper, president of the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest, said that of about 500,000 Indigenous people living in the Amazon, his group estimates that 147,000 have been infected by the virus and 3,000 have died.

-

Comando Matico volunteers Isai Eliaquin Sanancino, left, and Mery Fasabi, collect the leaves of a plant known locally as matico, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. As the new coronavirus spread quickly through Peru's Amazon, the indigenous Shipibo community decided to turn to the wisdom of their ancestors, gathering herbs, steeping them in water and breathing in the vapors. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Mery Fasabi, left, and Isai Eliaquin Sanancino, carry a pot of herbs steeped in boiling water to the home of a woman infected with the new coronavirus, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. Fasabi, along with 15 other volunteers have set up a makeshift treatment center known locally as Comando Matico that takes the holistic approach to treating the virus. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Sara Magin, who suffers from COVID-19 symptoms, sits inside a tent constructed from a bedsheet as she receives an herbal vapor therapy, at the Comando Matico headquarters, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. Volunteers have set up the makeshift treatment center that takes the holistic approach to treating the virus. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Comando Matico volunteer Isai Eliaquin Sanancino, treats Sara Magin, who suffers from COVID-19 symptoms, applying an ancestral practice of the Indigenous Shipibo, in Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. Unlike in hospitals, volunteers equipped in full protective gear, get close to patients, giving them words of encouragement and touching them through massage. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Comando Matico volunteers Mery Fasabi, left, and Isai Eliaquin Sanancino, heat an herbal remedy for a neighbor who has been suffering from COVID-19 symptoms, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020. Roberto Wikleff, a Shipibo man, said the 10 doctors, nurses and aides who usually staff a nearby clinic abandoned their posts when the new coronavirus pandemic arrived. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Boys watch as a government team disinfect the body of their relative Manuela Chavez, who died from symptoms related to the new coronavirus at the age of at the age of 88, after removing the body from inside her home in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020. In the Ucayali region, government rapid response teams deployed to a handful of indigenous communities have found infection rates as high as 80% through antibody testing. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Julia Lina who has been suffering from COVID-19 symptoms, rests in her bed enclosed in mosquito netting after receiving an herbal treatment from Comando Matico volunteers, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. Decades of underinvestment in public health care, combined with skepticism of modern medicine, mean many are not getting standard treatments like oxygen therapy to treat severe virus cases. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Art professor Iveri Sanchez and her students ready for their Amazonian street dances which they perform at a traffic light in hopes of receiving tips from the drivers, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020, amid the new coronavirus pandemic. Peru is home to one of Latin America's largest Indigenous populations, whose ancestors lived in the Andean country before the arrival of Spanish colonists. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

A homeless man sleeps against a wall adorned with a mural featuring a Shipibo Indigenous girl and Amazon rainforest animals, in Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Wednesday, Sept. 2, 2020. Peru is home to one of Latin America's largest Indigenous populations, whose ancestors lived in the Andean country before the arrival of Spanish colonists. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

A Shipibo Indigenous youth lugs a stalk of bananas at the port in Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020, amid the new coronavirus pandemic. Pucallpa's bustling port where wood, bananas and other fruit are loaded onto ships for export is believed to be one main source of contagion. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

A government team removes the body of Manuela Chavez, who died from symptoms related to the new coronavirus at the age of 88, from inside her home and places her in a casket, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020. At the peak of the outbreak in May and June, around 15 people were dying a day, said Juan Carlos Salas, director of Ucayali's regional health agency. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

A government team prepares to remove the body of Susana Cifuentes who died in her home from symptoms related to the new coronavirus at the age of 71, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. While the lucky are cured with ancestral ailments, the less fortunate often die at home. A government team travels from one spartan, thatch-roofed home to the next, removing the dead from their homes where they took their last breaths. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Children watch a government team remove the body of Susana Cifuentes, who died from symptoms related to the new coronavirus at the age of 71, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020. The Shipibo had tried to prevent COVID-19's entrance by blocking off roads and isolating themselves. But in May many came down with fevers, coughs, difficulty breathing and headaches. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

The cell phone of gravedigger Rider Sol Sol rests on a white cross marking the grave of a person who died from the new coronavirus, in a cemetery recently developed to bury victims of COVID-19, along a remote road known as "Kilometer 20," on the outskirts of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Wednesday, Sept. 2, 2020. The 48-year-old father of four said he and a crew of gravediggers buried up to 30 people a day at the height of the new coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Liliana Blas fries a batch of potatoes for lunch next to the coffin that contains the remains of her grandmother Susana Cifuentes, who died at the age of 71 from symptoms related to COVID-19, inside her house in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. Decades of underinvestment in public health care, combined with skepticism of modern medicine, mean many are not getting standard treatments like oxygen therapy to treat severe virus cases. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Covered in a disinfectant mist, the body of Susana Cifuentes, who died in her home from symptoms related to COVID-19 at the age of 71, is propped up on a chair as a government team prepares to remove her body, in the Shipibo Indigenous community Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. In the Ucayali region, government rapid response teams deployed to a handful of indigenous communities have found infection rates as high as 80% through antibody testing. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Government team members prepare to remove the body of Cruz Amanda Vargas, who died from symptoms related to the new coronavirus at the age of 84, from inside her home, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020. At the peak of the outbreak in May and June, around 15 people were dying a day, said Juan Carlos Salas, director of Ucayali's regional health agency. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

Family members weep during the burial of Manuela Chavez, who died from symptoms related to the new coronavirus at the age of 88, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Monday, Aug. 31, 2020. The Shipibo had tried to prevent COVID-19's entrance by blocking off roads and isolating themselves. But in May many came down with fevers, coughs, difficulty breathing and headaches. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd) -

The body of Susana Cifuentes who died in her home from symptoms related to COVID-19 at the age of 71, sits on bed wrapped in a black bag and secured by tape, as a government team prepares to remove it, in the Shipibo Indigenous community of Pucallpa, in Peru's Ucayali region, Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

While the lucky recover with ancestral remedies, the less fortunate often die at home. A government team travels from one spartan, thatch-roofed home to the next, plucking the dead from the beds and chairs where they took their last breaths. The poor are taken to the COVID-19 cemetery and interred in the burnt-orange dirt.

Rider Sol Sol, 48, said he and a crew of gravediggers buried up to 30 people a day at the height of the pandemic. The father of four had been out of work before getting this gravedigger's job.

"I give thanks to God that I have a job," he said.

These days, with the death count lower, he is the only man working most days. Alone amidst rows of white crosses, he tries not to let his mind drift toward the what ifs. The bodies come with a name and a number and he does not ponder their stories.

He keeps his mask on, digs into the earth and drinks from a bottle with matico.

© 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.