Nobel win for Swede who unlocked secrets of Neanderthal DNA (Update)

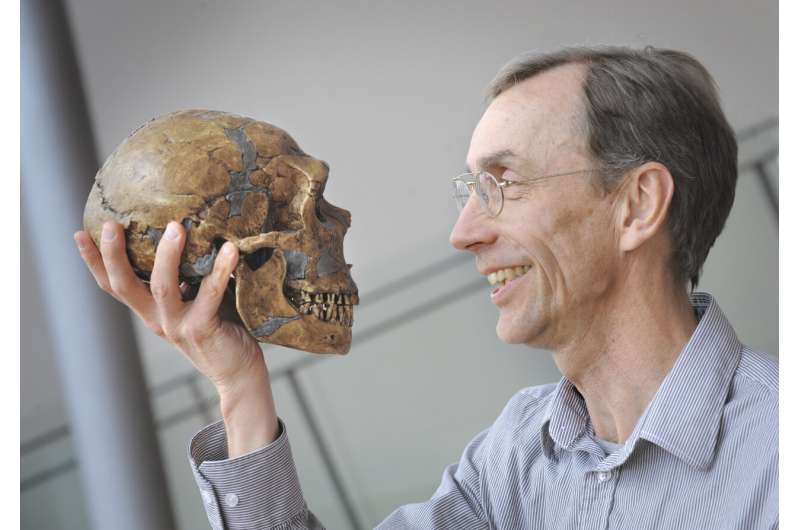

Swedish scientist Svante Paabo won the Nobel Prize in medicine Monday for his discoveries on human evolution that provided key insights into our immune system and what makes us unique compared with our extinct cousins, the award's panel said.

Paabo spearheaded the development of new techniques that allowed researchers to compare the genome of modern humans and that of other hominins—the Neanderthals and Denisovans.

While Neanderthal bones were first discovered in the mid-19th century, only by unlocking their DNA—often referred to as the code of life—have scientists been able to fully understand the links between species.

This included the time when modern humans and Neanderthals diverged as a species, determined to be around 800,000 years ago, said Anna Wedell, chair of the Nobel Committee.

"Paabo and his team also surprisingly found that gene flow had occurred from Neanderthals to Homo sapiens, demonstrating that they had children together during periods of co-existence," she said.

This transfer of genes between hominin species affects how the immune system of modern humans reacts to infections, such as the coronavirus. People outside Africa have 1-2% of Neanderthal genes.

Paabo and his team also managed to extract DNA from a tiny finger bone found in a cave in Siberia, leading to the recognition of a new species of ancient humans they called Denisovans.

Wedell described this as "a sensational discovery" that subsequently showed Neanderthals and Denisovan to be sister groups which split from each other around 600,000 years ago. Denisovan genes have been found in up to 6% of modern humans in Asia and Southeast Asia, indicating that interbreeding occurred there too.

"By mixing with them after migrating out of Africa, homo sapiens picked up sequences that improved their chances to survive in their new environments," said Wedell. For example, Tibetans share a gene with Denisovans that helps them adapt to the high altitude.

"Svante Pääbo has discovered the genetic make up of our closest relatives, the Neanderthals and the Denison hominins," Nils-Göran Larsson, a Nobel Assembly member, told the Associated Press after the announcement.

"And the small differences between these extinct human forms and us as humans today will provide important insight into our body functions and how our brain has developed."

Paabo said he was surprised to learn of his win on Monday.

"So I was just gulping down the last cup of tea to go and pick up my daughter at her nanny where she has had an overnight stay, and then I got this call from Sweden and I of course thought it had something to do with our little summer house in Sweden. I thought, 'Oh the lawn mower's broken down or something,'" he said in an interview posted on the official home page of the Nobel Prizes.

He mused about what would have happened if Neanderthals had survived another 40,000 years. "Would we see even worse racism against Neanderthals, because they were really in some sense different from us? Or would we actually see our place in the living world quite in a different way when we would have other forms of humans there that are very like us but still different," he said.

Paabo, 67, performed his prizewinning studies in Germany at the University of Munich and at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. He is the son of Sune Bergstrom, who won the Nobel prize in medicine in 1982. According to the Nobel Foundation, it's the eighth time that the son or daughter of a Nobel laureate also won a Nobel Prize.

Scientists in the field lauded the Nobel Committee's choice this year.

David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, said he was thrilled the group honored the field of ancient DNA, which he worried might "fall between the cracks."

By recognizing that DNA can be preserved for tens of thousands of years—and developing ways to extract it—Paabo and his team created a completely new way to answer questions about our past, Reich said. That work was the basis for an "explosive growth" of ancient DNA studies in recent decades.

"It's totally reconfigured our understanding of human variation and human history," Reich said.

Dr. Eric Green, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, called it "a great day for genomics," a relatively young field first named in 1987.

The Human Genome project, which ran from 1990-2003, "got us the first sequence of the human genome, and we've improved that sequence ever since," Green said. Since then, scientists developed new cheaper, extremely sensitive methods for sequencing DNA.

When you sequence DNA from a fossil millions of years old, you only have "vanishingly small amounts" of DNA, Green said. Among Paabo's innovations was figuring out the laboratory methods for extracting and preserving these tiny amounts of DNA. He was then able to lay pieces of the Neanderthal genome sequence against the human sequencing coming out of the Human Genome Project.

Paabo's team published the first draft of a Neanderthal genome in 2009. The team sequenced more than 60% of the full genome from a small sample of bone, after contending with decay and contamination from bacteria.

"We should always be proud of the fact that we sequenced our genome. But the idea that we can go back in time and sequence the genome that doesn't live anymore and something that's a direct relative of humans is truly remarkable," Green said.

Katerina Harvati-Papatheodorou, professor of paleoanthropology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, said the award also underscores the importance of understanding humanity's evolutionary heritage to gain insights about human health today.

"The most recent example is the finding that genes inherited from our Neanderthal relatives ... can have implications for one's susceptibility to COVID infections," she said in an email to the AP.

The medicine prize kicked off a week of Nobel Prize announcements. It continues Tuesday with the physics prize, with chemistry on Wednesday and literature on Thursday. The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize will be announced on Friday and the economics award on Oct. 10.

Last year's medicine recipients were David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian for their discoveries into how the human body perceives temperature and touch.

The prizes carry a cash award of 10 million Swedish kronor (nearly $900,000) and will be handed out on Dec. 10. The money comes from a bequest left by the prize's creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who died in 1895.

Nobel Committee press release: The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2022

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet

has today decided to award

the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

to

Svante Pääbo

for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution

Humanity has always been intrigued by its origins. Where do we come from, and how are we related to those who came before us? What makes us, Homo sapiens, different from other hominins?

Through his pioneering research, Svante Pääbo accomplished something seemingly impossible: sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal, an extinct relative of present-day humans. He also made the sensational discovery of a previously unknown hominin, Denisova. Importantly, Pääbo also found that gene transfer had occurred from these now extinct hominins to Homo sapiens following the migration out of Africa around 70,000 years ago. This ancient flow of genes to present-day humans has physiological relevance today, for example affecting how our immune system reacts to infections.

Pääbo's seminal research gave rise to an entirely new scientific discipline; paleogenomics. By revealing genetic differences that distinguish all living humans from extinct hominins, his discoveries provide the basis for exploring what makes us uniquely human.

Where do we come from?

The question of our origin and what makes us unique has engaged humanity since ancient times. Paleontology and archeology are important for studies of human evolution. Research provided evidence that the anatomically modern human, Homo sapiens, first appeared in Africa approximately 300,000 years ago, while our closest known relatives, Neanderthals, developed outside Africa and populated Europe and Western Asia from around 400,000 years until 30,000 years ago, at which point they went extinct. About 70,000 years ago, groups of Homo sapiens migrated from Africa to the Middle East and, from there they spread to the rest of the world. Homo sapiens and Neanderthals thus coexisted in large parts of Eurasia for tens of thousands of years. But what do we know about our relationship with the extinct Neanderthals? Clues might be derived from genomic information. By the end of the 1990's, almost the entire human genome had been sequenced. This was a considerable accomplishment, which allowed subsequent studies of the genetic relationship between different human populations. However, studies of the relationship between present-day humans and the extinct Neanderthals would require the sequencing of genomic DNA recovered from archaic specimens.

A seemingly impossible task

Early in his career, Svante Pääbo became fascinated by the possibility of utilizing modern genetic methods to study the DNA of Neanderthals. However, he soon realized the extreme technical challenges, because with time DNA becomes chemically modified and degrades into short fragments. After thousands of years, only trace amounts of DNA are left, and what remains is massively contaminated with DNA from bacteria and contemporary humans. As a postdoctoral student with Allan Wilson, a pioneer in the field of evolutionary biology, Pääbo started to develop methods to study DNA from Neanderthals, an endeavor that lasted several decades.

In 1990, Pääbo was recruited to University of Munich, where, as a newly appointed Professor, he continued his work on archaic DNA. He decided to analyze DNA from Neanderthal mitochondria—organelles in cells that contain their own DNA. The mitochondrial genome is small and contains only a fraction of the genetic information in the cell, but it is present in thousands of copies, increasing the chance of success. With his refined methods, Pääbo managed to sequence a region of mitochondrial DNA from a 40,000-year-old piece of bone. Thus, for the first time, we had access to a sequence from an extinct relative. Comparisons with contemporary humans and chimpanzees demonstrated that Neanderthals were genetically distinct.

Sequencing the Neanderthal genome

As analyses of the small mitochondrial genome gave only limited information, Pääbo now took on the enormous challenge of sequencing the Neanderthal nuclear genome. At this time, he was offered the chance to establish a Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany. At the new Institute, Pääbo and his team steadily improved the methods to isolate and analyze DNA from archaic bone remains. The research team exploited new technical developments, which made sequencing of DNA highly efficient. Pääbo also engaged several critical collaborators with expertise on population genetics and advanced sequence analyses. His efforts were successful. Pääbo accomplished the seemingly impossible and could publish the first Neanderthal genome sequence in 2010. Comparative analyses demonstrated that the most recent common ancestor of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens lived around 800,000 years ago.

Pääbo and his co-workers could now investigate the relationship between Neanderthals and modern-day humans from different parts of the world. Comparative analyses showed that DNA sequences from Neanderthals were more similar to sequences from contemporary humans originating from Europe or Asia than to contemporary humans originating from Africa. This means that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens interbred during their millennia of coexistence. In modern day humans with European or Asian descent, approximately 1-4% of the genome originates from the Neanderthals.

A sensational discovery: Denisova

In 2008, a 40,000-year-old fragment from a finger bone was discovered in the Denisova cave in the southern part of Siberia. The bone contained exceptionally well-preserved DNA, which Pääbo's team sequenced. The results caused a sensation: the DNA sequence was unique when compared to all known sequences from Neanderthals and present-day humans. Pääbo had discovered a previously unknown hominin, which was given the name Denisova. Comparisons with sequences from contemporary humans from different parts of the world showed that gene flow had also occurred between Denisova and Homo sapiens. This relationship was first seen in populations in Melanesia and other parts of South East Asia, where individuals carry up to 6% Denisova DNA.

Pääbo's discoveries have generated new understanding of our evolutionary history. At the time when Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa, at least two extinct hominin populations inhabited Eurasia. Neanderthals lived in western Eurasia, whereas Denisovans populated the eastern parts of the continent. During the expansion of Homo sapiens outside Africa and their migration east, they not only encountered and interbred with Neanderthals, but also with Denisovans .

Paleogenomics and its relevance

Through his groundbreaking research, Svante Pääbo established an entirely new scientific discipline, paleogenomics. Following the initial discoveries, his group has completed analyses of several additional genome sequences from extinct hominins. Pääbo's discoveries have established a unique resource, which is utilized extensively by the scientific community to better understand human evolution and migration. New powerful methods for sequence analysis indicate that archaic hominins may also have mixed with Homo sapiens in Africa. However, no genomes from extinct hominins in Africa have yet been sequenced due to accelerated degradation of archaic DNA in tropical climates.

Thanks to Svante Pääbo's discoveries, we now understand that archaic gene sequences from our extinct relatives influence the physiology of present-day humans. One such example is the Denisovan version of the gene EPAS1, which confers an advantage for survival at high altitude and is common among present-day Tibetans. Other examples are Neanderthal genes that affect our immune response to different types of infections.

What makes us uniquely human?

Homo sapiens is characterized by its unique capacity to create complex cultures, advanced innovations and figurative art, as well as by the ability to cross open water and spread to all parts of our planet. Neanderthals also lived in groups and had big brains. They also utilized tools, but these developed very little during hundreds of thousands of years. The genetic differences between Homo sapiens and our closest extinct relatives were unknown until they were identified through Pääbo's seminal work. Intense ongoing research focuses on analyzing the functional implications of these differences with the ultimate goal of explaining what makes us uniquely human.

More information: www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medi … dvanced-information/

© 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.