This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Fermentation may have driven human brain evolution

The large, capable human brain is a marvel of evolution, but how it evolved from a smaller primate brain into the creative, complex organ of today is a mystery. Scientists can pinpoint 'when' our evolutionary ancestors evolved larger brains, which roughly tripled in size as human ancestors evolved from the bipedal primates known as Australopithecines. But 'why' it happened when it did—what spurred that change—has remained elusive.

While some have theorized that the use of fire, and the subsequent invention of cooking, gave our ancestors enough nourishment for our larger-brained ancestors to become dominant, a new theory points to a different spark: fermentation.

The key to understanding how our brains grew is most likely rooted in what—and how—we eat, said Erin Hecht, one of the authors of "Fermentation technology as a driver of human brain expansion," which was published in Communications Biology.

"Brain tissue is metabolically expensive," said the Human Evolutionary Biology assistant professor. "It requires a lot of calories to keep it running, and in most animals, having enough energy just to survive is a constant problem."

For larger-brained Australopiths to survive, therefore, something must have changed in their diet. Theories put forward have included changes in what these human ancestors consumed or, most popularly, that the discovery of cooking allowed them to garner more usable calories from whatever they ate.

But the problem with this theory is that the earliest evidence places the use of fire at approximately 1.5 million years ago—significantly later than the development of the hominid brain.

"Our ancestors' cranial capacity began increasing 2.5 million years ago, which conservatively gives us about a 1-million-year gap in the timeline between brain size increasing and the possible emergence of cooking technology," explained Katherine L. Bryant, one of the paper's co-authors and currently a researcher at the Institute for Language, Communication, and the Brain at Aix-Marseille Université in France.

"Some other dietary change must have been releasing metabolic constraints on brain size, and fermentation seems like it could fit the bill."

Hecht added, "Whatever changed in their diets had to have happened before brains started getting bigger."

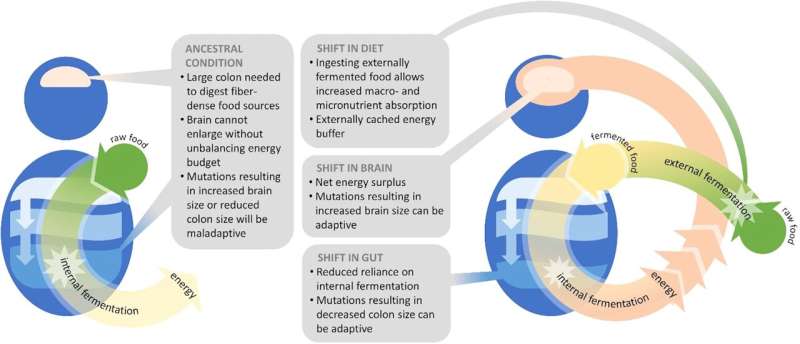

She continued, noting that during the last few years researchers have postulated other options, such as the consumption of rotting meat. In this new paper, Hecht and her team offer a different hypothesis: that cached (or saved) food fermented, and that this 'pre-digested' food provided a more accessible form of nourishment, fueling that bigger brain and allowing our larger-brained ancestors to survive and thrive through natural selection.

The shift was probably a happy accident. "This was not necessarily an intentional endeavor," Hecht posited. "It may have been an accidental side effect of caching food. And maybe, over time, traditions or superstitions could have led to practices that promoted fermentation or made fermentation more stable or more reliable."

This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the human large intestine is proportionally smaller than that of other primates, suggesting that we adapted to food that was already broken down by the chemical process of fermentation. In addition, fermented foods are found in all cultures and across food groups, from Europe's wine and cheese to Asia's soy sauce and natto, or soy beans.

Hecht suggested that an additional study of brain responses to fermented and non-fermented foods might be useful, as might one of olfactory and taste receptors, perhaps using ancient DNA. For the evolutionary biologist, these are all fertile areas for other researchers to pick up on. (Hecht's focus is more on "how brain circuits have evolved to support complex behaviors" with research on both living humans and dogs.)

As research progresses, Bryant sees possibilities for a wide range of benefits. "This hypothesis also gives us as scientists even more reasons to explore the role of fermented foods on human health and the maintenance of a healthy gut microbiome," she said. "There have been a number of studies in recent years linking gut microbiome to not only physical but mental health."

More information: Katherine L. Bryant et al, Fermentation technology as a driver of human brain expansion, Communications Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-023-05517-3