This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Research team identifies 'protective switches' in SARS-CoV-2 protein that defend against immune system

Over 700 million people were infected and almost seven million died, making SARS-CoV-2 the most devastating pandemic of the 21st century. Vaccines and medication against COVID-19 have been able to mitigate the course of the disease in many people and contain the pandemic. However, the danger of further outbreaks has not been averted. The virus is constantly mutating, which enables it to infect human cells and multiply more and more effectively. In addition, it is developing a variety of strategies against the human immune system in a "molecular arms race."

A team led by researchers from the University of Göttingen has now discovered various "protective switches" in the coronavirus that shield it from attacks by the immune system. The results are published in Nature Communications.

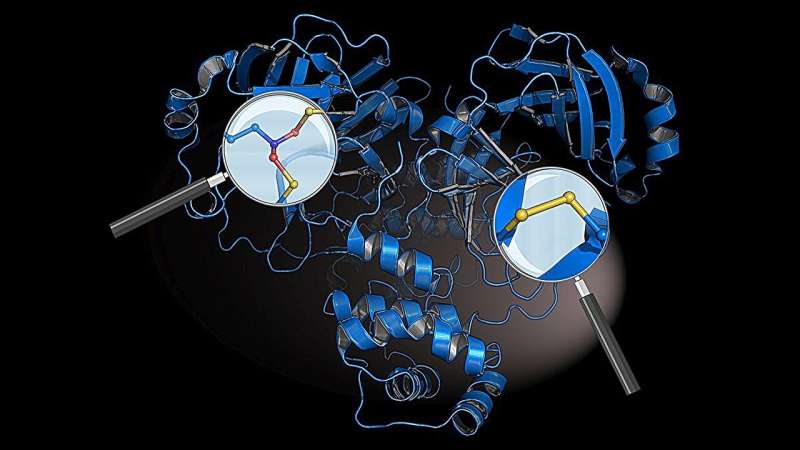

The researchers identified two previously unknown chemical protective switches in the virus's main "protease"—a crucial protein of the coronavirus. The most important drug against COVID-19, called Paxlovid, targets this protein. The virus uses its main protease to cut out the other virus proteins in our infected cells, thus driving its own replication. It uses the amino acid cysteine to do this.

"From a chemical point of view, this could be an Achilles heel for the coronavirus, as cysteines can be destroyed by highly reactive oxygen radicals, which our immune system uses to fight viruses," explains Professor Kai Tittmann, Molecular Enzymology Research Group at Göttingen University, who led and coordinated the study.

The protective switches mean the virus's main protease is protected against the immune system's bombardment by oxygen radicals: The protein is stabilized by one cysteine forming a disulfide with an adjacent cysteine via two sulfur atoms. This prevents the cysteine from being destroyed. At the same time, a bridge known as SONOS connects three parts of the protein between sulfur atoms (S), oxygen atoms (O), and a nitrogen atom (N). This prevents radicals from damaging its three-dimensional structure.

Tittmann says, "It is fascinating to see how chemically elegant and effective the coronavirus is in defending itself against the immune system. Interestingly, a coronavirus discovered earlier—severe acute respiratory syndrome, also known as SARS-CoV-1—which triggered the 2002 to 2004 outbreak, also has these protective switches. This is the first time this has been shown."

Despite this scientific first, the researchers were not satisfied with just discovering "protective switches." With the chemical blueprint in hand, they set about searching for molecules that can bind precisely to the "protective switches," therefore inhibiting the virus's main protease. They identified such molecules not only in the test tube, but also in infected cells.

"This type of molecule opens up the potential for new therapeutic interventions which will stop coronaviruses in their tracks," says Lisa-Marie Funk, first author of the study, also at Göttingen University's Molecular Enzymology research group.

More information: Lisa-Marie Funk et al, Multiple redox switches of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease in vitro provide opportunities for drug design, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-44621-0