This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

How fusion proteins hijack gene regulators to spur childhood cancer

Many childhood cancers start with a hijacking at the molecular level. A group of abnormal proteins known as fusion proteins aberrantly engages with a collection of proteins that switches genes on and off. As a result, genes that should be activated get repressed, and genes that should be repressed get activated, causing cancer.

University at Buffalo researchers have now shed more light on the molecular mechanism behind this hijacking. Their study, published in Nature Communications, shows that the fusion proteins and a gene regulatory protein complex interact through their unfolded, floppy regions, known as disordered domains.

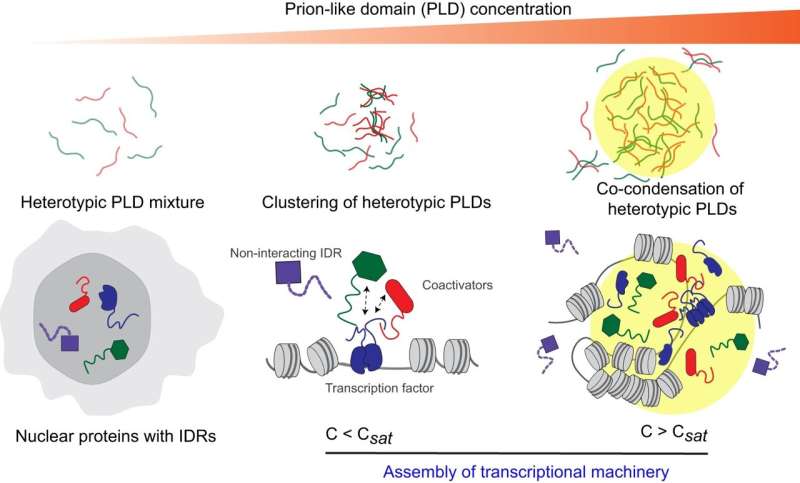

Despite their fuzzy nature, the disordered domains interact with a high degree of specificity by forming liquid-like droplets and blending them together.

"There has been a lot of evidence that disordered regions of proteins play a role in cancer and other major human diseases, but the question has been how," says the study's senior corresponding author, Priya Banerjee, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Physics, within the UB College of Arts and Sciences.

"Here we show that this crucial networking event between the fusion proteins and the gene regulatory protein complex happens through their disordered domains and that there is a chemical specificity to this process."

Fusion proteins are the result of a piece of chromosome breaking off and attaching to another to form a fusion gene. Fusion proteins don't always lead to cancer, but some can alter the activity of other genes to the point where cells grow uncontrollably and cause cancer. These are known as fusion oncoproteins.

"In order for cancer to develop, a lot needs to go wrong. That is, a lot of gene mutation needs to happen. But in the case of some pediatric cancers, these fusion oncoproteins might be the sole culprit," says the study's lead author, Richoo Davis, Ph.D., a postdoc in Banerjee's lab. "So targeting oncoproteins alone might be sufficient enough to cure such childhood cancers."

Breakthrough studies by other groups have shown that fusion oncoproteins alter gene activity by hijacking a major chromatin remodeler known as the mammalian SWI/SNF complex. Almost 20% of all human cancers have a mutation in this protein complex.

Banerjee's team wanted to know how exactly fusion oncoproteins hijack the complex. Their new paper, which builds on their previous study published in 2021, finds that both the fusion oncoproteins and the mammalian SWI/SNF complex interact through their respective disordered domains.

Unable to fold into unique three-dimensional shapes, disorder domains have long remained enigmatic. Scientific dogma for decades was that protein interactions happen via proteins' structured regions coming together in a lock-and-key-like mechanism.

However, research in the last two decades has shown that almost 30% of the human proteome is disordered and that disorder regions drive some key biological processes and major human diseases.

Banerjee's team looked at a specific disordered domain, called prion-like domains, from fusion oncoproteins and the gene regulatory complex and found these particular domains form liquid-like droplets, or membrane-less organelles, in the nucleus of the cell.

Molecular complexes form from the prion-like domains of both the fusion oncoproteins and the gene regulators when their networking begins. These complexes then combine to form liquid-like droplets or co-condensates. To study this further, Davis used a blue light-activated droplet-forming system that allowed the team to view these processes more clearly. However, there is exquisite specificity of what can co-condense together to activate aberrant gene expression leading to cancer.

"We found that disordered regions of repressor proteins don't really enrich in the droplets formed by prion-like domains, and we think that this selectivity in molecular networking is an important mechanism by which fusion oncoproteins contributes to cancer development," Banerjee says.

Once the fusion proteins have successfully hijacked the complex, they essentially can take it away from the genes it's supposed to turn on—and bring it to genes it should not turn on.

In the future, pharmaceutical drugs could be developed to target the abnormal networking of fusion proteins with the SWI/SNF complex in order to cure cancer.

"This fundamental research is crucial," Banerjee says. "We cannot cure a fatal human disease unless we fully understand the molecular wiring underneath it."

More information: Richoo B. Davis et al, Heterotypic interactions can drive selective co-condensation of prion-like low-complexity domains of FET proteins and mammalian SWI/SNF complex, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-44945-5