Cell reprogramming: much promise, many hurdles

Research in reprogrammed cells, which on Monday earned the 2012 Nobel Prize, has been hailed as a new dawn for regenerative medicine but remains troubled by several clouds.

Britain's John Gurdon and Japan's Shinya Yamanaka were honoured with the world's paramount award in medicine for induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

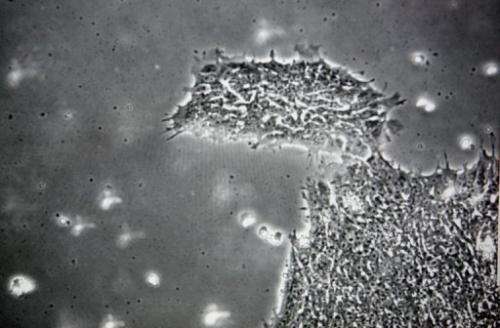

They discovered that a mature, adult cell can be turned back to an infant, versatile state called a stem cell.

First theorised in the late 19th century, stem cells are touted as a source of replacement tissue, fixing almost anything from malfunctioning hearts and lungs, damaged spines, Parkinson's disease or even baldness.

The first human trials were launched only in 2010, and progress has been dogged by the contested use of stem cells taken from early-stage embryos, where the most adaptable, or pluripotent, cells are found.

Created by Yamanaka in 2006, iPSCs ease the moral row as they derive from adult cells and not embryos, said University of Oxford ethics professor Julian Savulescu.

Ordinary skin cells can be used as the starting material.

"Many people objected to the creation of embryos for research, describing it as cannabalizing human beings," he said.

George W. Bush "retarded the field for years" by blocking US government funds for human embryonic stem cell research, a decision reversed in 2009 by President Barack Obama, he added.

Last year, Europe's top court banned patents of stem cells when their extraction caused the destruction of a human embryo—a decision lamented by scientists but hailed by Catholic bishops.

After many years in the lab, stem cells are now cautiously being tested on humans.

In 2010, US biotech firm ACT began the first stem cell trial in the world on patients with retinal disease that causes blindness.

Last year, doctors in the United States gave 16 heart attack victims an infusion of cardiac stem cells, restoring vitality in heart muscle and blood-pumping ability.

In Sweden, a 36-year-old man was given an artificial windpipe, which used a synthetic "scaffold" covered with his own stem cells.

But none of these and other small-scale stem cell trials involve iPSCs.

Researchers freely admit that this fledgling technology has many unknowns—and all must be resolved before tests can proceed on human volunteers.

One early shock was that, among lab mice, iPSCs developed into tumours, a problem traced to a reprogramming gene and the retroviruses used to generate the cells.

To create an iPSC, "we have to genetically modify [the adult cell] by introducing at least three different genes," said Paul Fairchild, director of the Oxford Stem Cell Institute.

"It is that process of genetic modification which can risk transforming the cell, and making it cancerous. That is where the safety concerns lie."

One argument in favour of iPSCs is that because they are derived from one's own DNA, they will be accepted by the immune defences as friends and thus be spared from attack.

But last year a study found that certain kinds of iPSCs may be rejected by the immune system.

"The assumption that cells derived from iPSCs are totally immune-tolerant has to be re-evaluated before considering human trials," warned Yang Xu, a professor of biology at the University of California at San Diego.

In February, a team led by Joseph Ecker of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California found that the transformation from adult cell to stem cell can be incomplete.

DNA errors pop up in an area of the genome called the epigenome, which is the switching system that turns genes on or off and determines their level of activity.

"Lots of people are working on getting over the roadblocks," said Fairchild, adding, with optimism: "It is only a matter of time."

(c) 2012 AFP