Researchers find new way to prevent dangerous blood clots

(Medical Xpress)—For the first time, scientists at the UNC School of Medicine have shown that eliminating the enzyme factor XIII reduces the number of red blood cells trapped in a clot, resulting in a 50 percent reduction in the size of the clot.

The finding, featured today in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, has major implications for people at high risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a condition that – together with its deadly cousin pulmonary embolism – affects 300,000 to 600,000 people in the United States every year. Between 60,000 and 100,000 people die from these conditions every year in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"If we can develop a treatment that exploits this discovery to reduce the size of blood clots, it would represent a whole new approach to treating thrombosis that's different from anything else on the market," said Alisa Wolberg, PhD, associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and senior author of the JCI paper. "We think reducing factor XIII activity could be helpful to a large number of people, perhaps including some who cannot take existing 'blood-thinning' medications."

The ability for blood to clot is crucial to our health; by stanching bleeding long enough to allow healing, clots keep us from bleeding to death from injuries. But in the wrong circumstances, clots can pose a significant health hazards.

In patients with DVT, clots that form inside blood vessels, usually in the legs, obstruct the flow of blood, leading to pain and swelling while raising the risk of pulmonary embolism – a life-threatening condition in which a clot breaks away, travels through the bloodstream, and obstructs a crucial artery in the lungs.

DVT often occurs during periods of restricted movement, such as prolonged sitting common during a long trip. Also, pregnancy, cancer, genetics, certain kinds of injuries, surgeries and medications can raise the risk of developing DVT.

Many patients at high risk for developing clots regularly take blood-thinning drugs, such as warfarin, which stifles the body's ability to make fibrin – the fibrous protein that binds a clot together. But these drugs can raise the risk of excessive bleeding, can cause side effects, and aren't appropriate for all patients.

"What's needed is a drug that reduces the risk of forming large clots but still allows you to form a clot when you need one to stanch bleeding," Wolberg said. "The biological pathway we've discovered may make it possible to strike that balance."

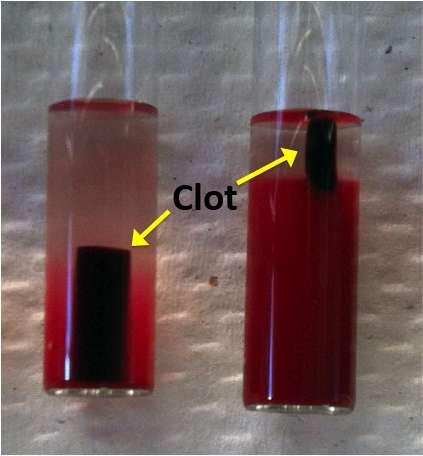

In experiments using mice and human blood, the researchers examined the role of a protein called factor XIII in clot formation. To their surprise, they found that mice incapable of producing factor XIII formed clots that were half the size of the clots produced by normal mice.

"That difference in itself was extremely striking," said Maria Aleman, PhD, first author of the JCI paper and a graduate student in Wolberg's lab at the time of the study. "Then, the second surprise was discovering that the size difference was actually due to a reduced number of red blood cells in the clot. Since no previous studies had suggested that it was possible to manipulate the number of red blood cells, we knew we had found something new."

Factor XIII appears to play a crucial role in helping the fibrin matrix keep its integrity during clot formation. Normally, the fibrin matrix forms a strong mesh in and around the clot, trapping red blood cells within. Without factor XIII, some red blood cells are squeezed out, resulting in a much smaller clot.

Unlike existing drugs that reduce the formation of fibrin, a drug that reduces factor XIII could potentially cut the body's ability to produce large, dangerous clots without sacrificing the ability to produce small, beneficial clots.

Such a drug, then, would benefit patients at risk of developing the most dangerous kinds of clots.