Diagnosing Ebola before symptoms arrive

Boston University researchers, led by John Connor, associate professor of microbiology at the Boston University School of Medicine and researcher at Boston University's National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL), in collaboration with the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Disease (USAMRIID), studied data from 12 monkeys exposed to Ebola virus, and discovered a common pattern of immune response among the ones that got sick. This response occurred four days before the onset of fever—the first observable symptom of infection. The work, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, suggests a possible biomarker for early diagnosis of the disease.

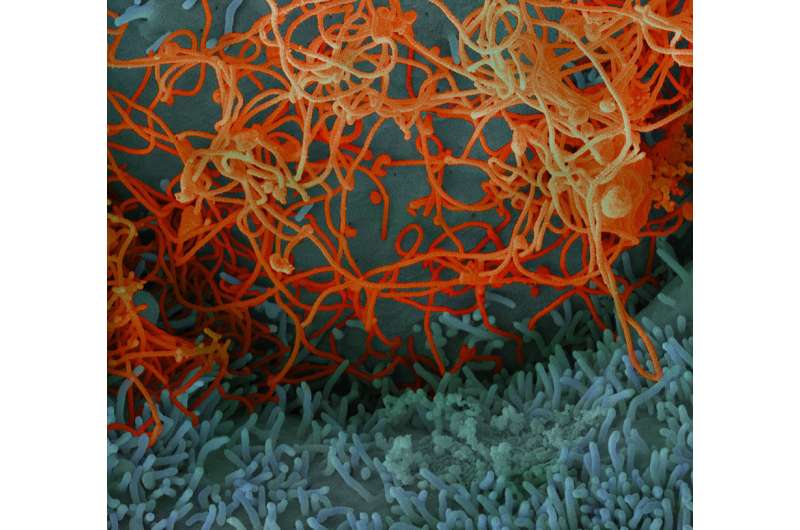

Currently, there is no way to diagnose Ebola until symptoms arrive—and the fever, severe headache, and muscle pain that mark Ebola can strike victims anytime between 2 and 21 days after exposure.

"Right now, we wait for diagnosis until the virus spills out of primary infection sites into the blood," says Emily Speranza, who recently received her PhD from Boston University's Bioinformatics program and is the co-first author on the paper. "At that point, it's already tremendously far along."

"If you can start treating someone very, very early on after exposure, they're less likely to develop really severe disease," says Speranza. "And if you can identify people who are sick before they even show symptoms, you can better quarantine and actually control outbreaks."

Speranza's study began with an unexpected result from scientists at USAMRIID.

They had been trying to simulate the course of Ebola in monkeys, in a way that more closely mimicked the way humans become infected. Traditionally, scientists studying Ebola in primates inject a high dose of virus directly into a muscle. When infected that way, all the animals die within 10 days.

That's not how it works in people. "Humans are not necessarily going to be exposed to a needle injection of Ebola virus," says Speranza. "You're more likely to be exposed through cuts on your skin or through mucosal surfaces in your eyes, nose, or mouth."

So the scientists at USAMRIID tried a similar tactic. They infected 12 monkeys through the nose, using much less Ebola virus than usual. The researchers expected all the animals to grow sick at the same time, but they didn't; some died within the usual 10 days, one group died around day 13, another group lived to 21-22 days, and two of the animals never got sick at all.

"Prior to this result, there was no model that behaved like the disease that you and I would get, which is, we would probably be exposed, we'd walk around for somewhere between 2 to 21 days, and then we'd get sick," said John Connor, who is senior author on the paper. "And that's what this was trying to model: If I get sick in 5 days, and you get sick in 12 days or 17 days, are our immune responses different? All of a sudden you can ask that question."

Speranza, who studies the body's immune response to Ebola virus, sought to answer the question by looking at genes. "We were very curious to find out what was going on," she says. She started by looking at the innate immune response, the body's first defense against disease, trying to see which genes turned on, and when. When she looked at a group of signaling proteins called interferons, she found a pattern. In all the monkeys, no matter how long it took them to show symptoms, a handful of genes triggered by interferons—called the interferon-stimulated genes—kicked into gear four days before the animals spiked a fever. The genes showed up in the same pattern across all the subjects who got sick.

Speranza then compared the results to humans, using Ebola victim blood samples that had been collected and preserved during the 2014-2016 outbreak in Guinea. "We found not only the same genes going up," she says, "but in a similar order."

Connor notes that other scientists have found similar early immune responses in monkeys exposed to Lassa and humans exposed to influenza. Scientists still need to tease out more specific details of the human response to Ebola. "We looked at the most obvious things, which is this very loud innate immune response. Those are the trumpets," says Connor. "And there may be some piccolos playing that we can't hear. There may be some other specific signals that say, 'Oh, this actually is Ebola.'"

Finding those subtle signals will take more research, the scientists say, but this work, though preliminary, offers a promising first step toward early diagnosis. "We can now take the next step," says Speranza, "and actually start building that information into a biomarker for infection."

More information: E. Speranza el al., "A conserved transcriptional response to intranasal Ebola virus exposure in nonhuman primates before onset of fever," Science Translational Medicine (2018). stm.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/ … scitranslmed.aaq1016