First identification of brain's preparation for action

Neuroscientists at Bangor University and University College London have for the first time, identified the processes which occur in our brains milliseconds before we undertake a series of movements, crucial for speech, handwriting, sports or playing a musical instrument. They have done so by measuring tiny magnetic fields outside the participants' head and identifying unique patterns making up each sequence before it is executed. They identified differences between neural patterns which lead to a more skilled as opposed to a more error-prone execution.

The research, funded by the Wellcome Trust, is published in Neuron Issue date 7 FEBRUARY 2019 (DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.018). Following further research, this new information could lead to the development of interventions which would assist with rehabilitation post-stroke or improve life for people living with stutter, dyspraxia or other similar conditions.

Lead author Dr. Katja Kornysheva, of Bangor University's School of Psychology explained the significance of the findings:

"Using a non-invasive technique which measures ongoing brain activity on a millisecond-by-millisecond basis, we were able to track brain activity as participants prepared and then moved their fingers from memory. This revealed that the brain prepares for complex actions in the milliseconds beforehand by 'stacking' the actions to be taken, in the correct order."

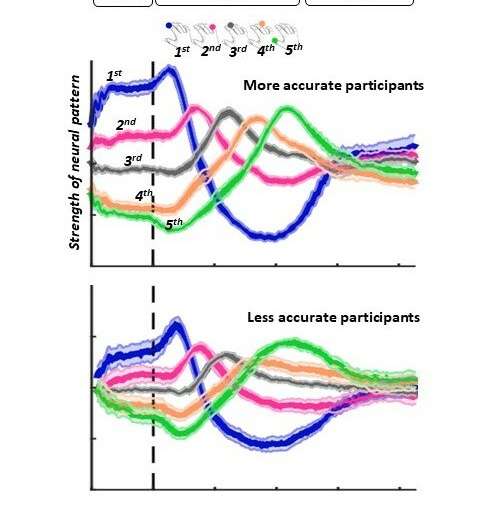

"Reviewing the brain impulses, we could see that when participants were producing the sequences correctly and accurately, with no errors, each activity was spaced and ordered in advance of being executed. However, when mistakes occurred, the 'queuing' of actions was visibly less well-defined as separate and distinct actions. It appears that the more closely bunched and less-defined 'queuing' was, the more participants committed errors in sequence production and timing.

Co- researcher and author, Prof Neil Burgess, of UCL's Inst of Cognitive Neuroscience commented:

"To our surprise we also found that this preparatory pattern is primarily reflecting a template for position (1st, 2nd, 3rd and so on) which can be reused across sequences—like cabinet drawers into which one can put different objects. This is a way for the brain to be efficient and flexible, by providing a blueprint for new sequences and staying organized."

"Unfortunately, disorders of sequence control and fluency can severely disrupt everyday life—with no treatment being predictively effective. Eventually, this research could lead to the development of 'as it happens' decoders which would provide instant feed-back to the user. This could help to 'train' their brains to create the correct preparation state and overcome difficulties such as a stutter or dyspraxia. We hope that the new understanding could also lead to the development of improved brain computer interfaces, used by people who are 'locked- in# or have whole body paralysis."

More information: Neuron (2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.018