Invasive brain-computer interfaces use thoughts to bring prostheses to life

Invasive brain-computer interfaces aim to improve the quality of life of severely paralyzed patients. Movement intentions are read out in the brain, and this information is used to control robotic limbs. A research team at the Knappschaftskrankenhaus Bochum Langendreer, University Clinic of Ruhr-Universität Bochum, has examined which errors can occur during communication between the brain and the robotic prosthesis and which of them are particularly significant. With the aid of a virtual reality model, the researchers found that a faulty alignment of the prosthesis, the so-called end effector, results in a measurable loss of performance. The Bochum-based researchers headed by Dr. Christian Klaes from the Department of Neurosurgery published the results in the journal Scientific Reports.

Three main sources of error

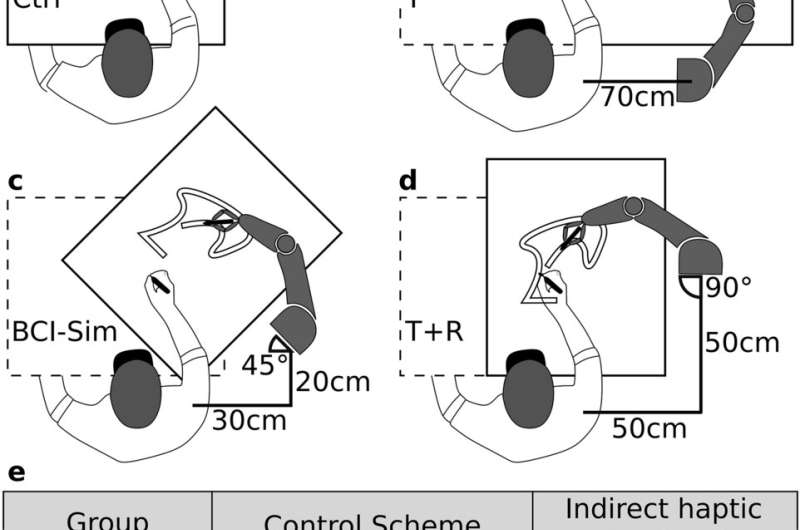

Brain-computer interfaces can enable severely paralyzed patients to move a prosthesis. In the invasive method, a measuring device implanted in the brain translates the signals from the nerve cells into control signals for the end effector, for example a robotic arm prosthesis. The Bochum-based researchers started with the assumption that three main factors have a negative impact on the control of the end-effector: the decoding error, the feedback error and the alignment error.

The decoding error describes the difference between the patient's real intention to move and the intention to move decoded from the brain signals by the decoder. Alignment error occurs when the end effector of the brain-computer interface is incorrectly positioned relative to the participant's natural arm. The feedback error of the brain-computer interface system arises from a lack of somatosensory feedback, i.e. the lack of feedback from the robot arm regarding touch. The Bochum team used a virtual reality model to analyze the misalignment and feedback errors—independently of the decoding error and also independently of each other.

One-to-one translation of movement intentions into movements

"Healthy study participants without sensorimotor disorders slipped into the role of patients with motor dysfunctions in virtual reality," explains Robin Lienkämper, lead author of the study. "Our model thus provides a one-to-one translation of movement intentions into end-effector movements, comparable to that of a patient using a faultless decoder."

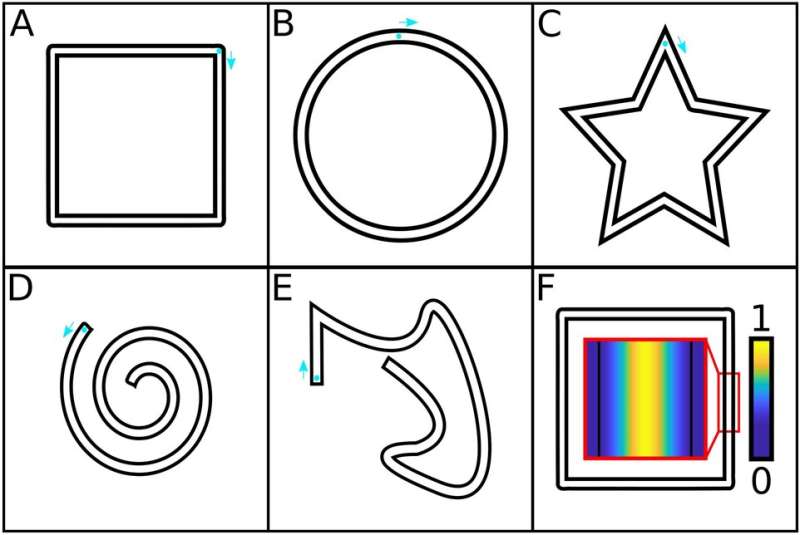

In virtual reality, the participants were given the task of drawing shapes with a pencil—a square, a circle, a star, a spiral and an asymmetrical shape. This corresponds to a frequently set task in experiments on brain-computer interfaces, which can be used to evaluate and compare motor performance under different conditions.

The controller was perceived as a pen by the test participants in the experiment. The researchers achieved the desired feedback effect by having the test person sit at a real table while drawing in the virtual world and the controller touching table surface. There were two groups to control the effect: one group received indirect haptic feedback, the other did not. This means that for the second group, the physical table was removed while the table remained visible in virtual reality.

Ideally, the robotic arm is incorporated in the body schema

Using the collated data, the research team showed that the lack of indirect haptic feedback alone had a minor impact, but amplified the effect of the misalignment. Based on the results, the researchers also suggested that a naturally positioned prosthesis could significantly improve the performance of patients with invasive brain-computer interfaces. They also hypothesized that anchoring the robotic arm to the patient's own body awareness would have a positive effect and improve motor performance. Ideally, a patient using a brain-computer interface would incorporate the robotic arm into their own body schema.

The researchers concluded their study by highlighting the importance of developing end effectors that enable better incorporation and more natural positioning. According to them, solutions such as exoskeletons or functional muscle stimulation should be considered. "The future of research now lies in using engineering to bring the scientific results to the patient," says Robin Lienkämper. He expects that, thanks to the commitment of the industry, applications suitable for everyday use will already be available in five to 10 years.

More information: Robin Lienkämper et al, Quantifying the alignment error and the effect of incomplete somatosensory feedback on motor performance in a virtual brain–computer-interface setup, Scientific Reports (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-84288-5