July 7, 2021 feature

Soft tissue regeneration in a cell-free scaffold microenvironment

In a new report now published on Scientific Reports, Irini Gerges and a team of scientists in Italy and the U.S. studied the importance of biomechanical and biochemical cues to create culture conditions suited for three-dimensional (3D) regenerative microenvironments and soft tissue formation. The team observed changes in adipogenesis relative to the 3D mechanical properties and created a gradient of three-dimensional microenvironments with different stiffnesses. The outcomes indicated a significant increase in the proportions of adipose tissue, while decreasing the stiffness of the 3D mechanical microenvironment. They compared this mechanical conditioning effect with biochemical regulation by loading the extracellular environments with a biological stimulant. The outcomes showed mechanical and biochemical conditioning sufficient to boost adipogenesis and influence tissue remodeling. The work can open new avenues to design 3D scaffolds to form microenvironments that regenerate large volumes of soft and adipose tissue for practical and direct implications in reconstructive and cosmetic surgery.

Soft tissue reconstruction

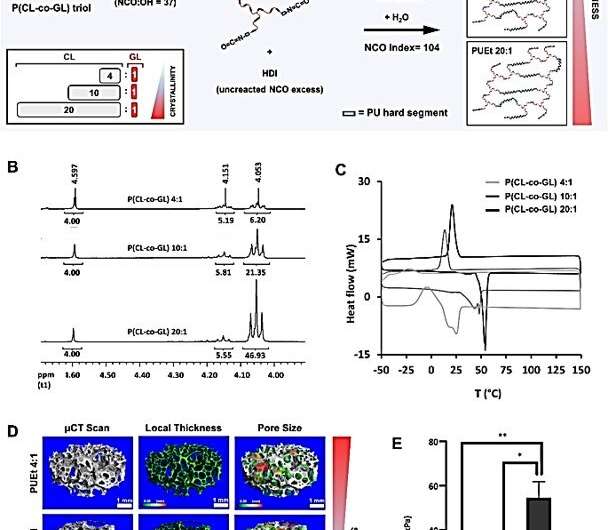

Soft tissue reconstruction approaches depend on inert fillers or autologous grafts; therefore, an unmet clinical need exists for effective solutions to restore soft tissues after surgery. Cell-free scaffold-based approaches are a promising solution due to their biocompatibility, adaptability to target tissue, cost-effectiveness and compliance with international manufacturing standards. Synthetic scaffolds are a scalable clinical solution because they can avoid regulatory and manufacturing hurdles compared to cell-based therapies. Three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds to regenerate clinically relevant soft tissue volumes have gained considerable progress at the clinical level as seen with medical grade scaffolds. Limitations of the material result from high local stiffness of the polymer filaments compared to the target tissue. It is therefore important to develop scaffolds specific to adipose tissue regeneration to regulate biomechanical cues to achieve appropriate cell and biomaterial interactions that are fundamental for adipogenesis. The team addressed key factors of the biological performance of polyurethane-based cross-linked porous biomaterials as scaffolds for soft tissue regeneration by focusing on the role of polymer chemistry and the microarchitecture. In this work, Gerges et al. modified the composition of polyester triol segments to synthesize a gradient of porous scaffolds that share similar physiochemical and morphological properties with diverse substrate stiffnesses to understand the impact of mechanical cues on adipogenesis.

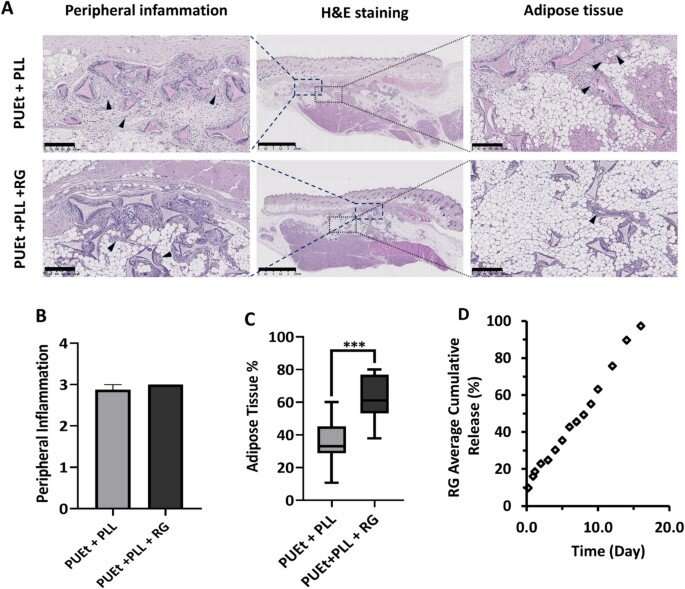

The scientists enhanced the regenerative microenvironment by using a scaffold loaded with a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist Rosiglitazone to induce adipocyte differentiation. They investigated the impact of the mechanical environment on the in vivo performance of a scaffold by fine tuning the scaffold mechanical properties without changing or altering the remaining physicochemical characters. By varying the degree of crosslinking, pore dimension and ratio of the hard and soft segments holding the macromolecular structure together, the team regulated the mechanical properties of a crosslinked polyurethane foam. Gerges et al. then focused on the degree of crystallinity of the soft segments and kept the ratio between the initiator and monomer constant, in order to maintain the same average molecular weight of the materials. After performing compression tests on the three versions of scaffold formulations, the team changed the ratio between amorphous and crystalline domains of the polyesters to successfully obtain three types of scaffold formulations. The researchers treated all scaffolds in this study to poly-L-lysine to promote cell adhesion on the material surfaces for non-specific cell-biomaterial interactions.

Understanding the function of the scaffold material

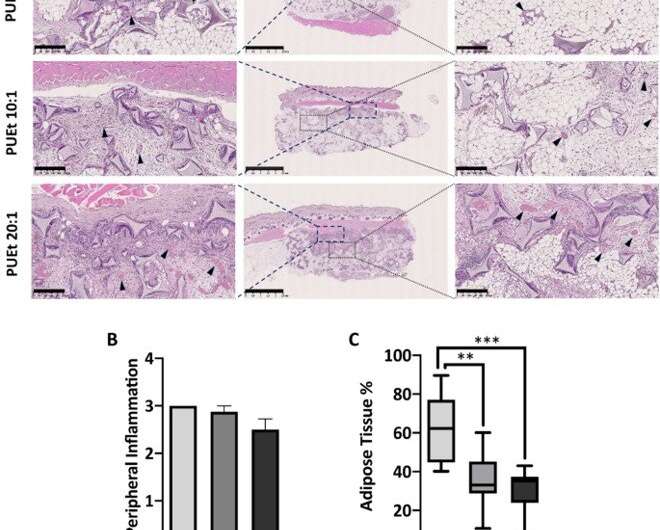

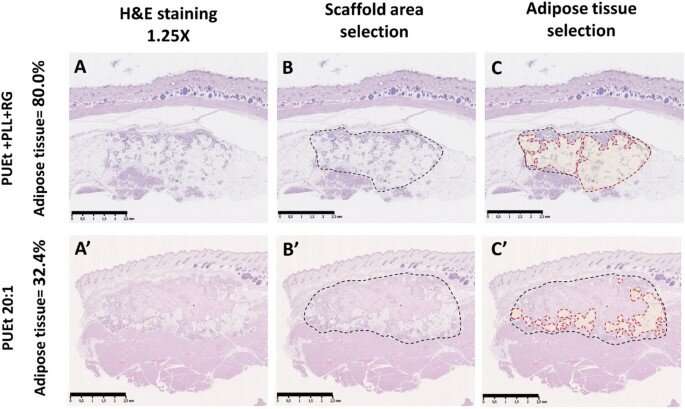

After implementing the scaffolds in animal models, the scientists did not observe abnormalities in them, and they conducted histological examinations on the scaffolds upon their retrieval. They noted capsule formation around the scaffold with moderate amounts of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells associated with chronic inflammatory infiltrates in all three groups of scaffolds. Among those groups tested, the scaffold material with the lowest elastic modulus maintained the highest adipose tissue percentage. Gerges et al. next investigated the impact of biochemical regulation by the local release of peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor agonist molecules in a neutral biomechanical framework. The concentrations of the molecules were sufficient to activate the corresponding receptors on the cells invading the scaffold from the adjacent surrounding tissue. The team credited the significant increase in the adipose tissue in the treated scaffolds to the cell-free environment induced by activating the specific receptors.

Outlook

In this way, Irini Gerges and colleagues studied the importance of biomechanical and biochemical cues to develop a 3D regenerative microenvironment for soft tissue formation based on two specific sets of experiments in animal models. The outcomes highlight the infiltration of adipose tissue with decreasing scaffold stiffness, and the benefits of scaffold mechanical properties to regenerate adipose tissue while inhibiting fibrous tissue formation. The results confirmed the capacity of mechanical and biochemical factors to equally promote adipose tissue formation under the described settings, to suggest that adequate mechanical signalling can boost adipogenesis by significantly influencing cell differentiation.

More information: Irini Gerges et al, Conditioning the microenvironment for soft tissue regeneration in a cell free scaffold, Scientific Reports (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-92732-9

Pattie S. Mathieu et al, Cytoskeletal and Focal Adhesion Influences on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Shape, Mechanical Properties, and Differentiation Down Osteogenic, Adipogenic, and Chondrogenic Pathways, Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews (2012). DOI: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2012.0014

Dirk Grafahrend et al, Degradable polyester scaffolds with controlled surface chemistry combining minimal protein adsorption with specific bioactivation, Nature Materials (2010). DOI: 10.1038/nmat2904

© 2021 Science X Network