COVID-19 mutations accelerated by virus-fighting enzyme in human cells, according to new research

Researchers have found the first experimental evidence explaining why the COVID-19 virus produces variants, such as delta and omicron, so quickly.

The findings, published Sept. 13 in the journal Scientific Reports, could help scientists predict the emergence of new coronavirus strains and possibly even produce vaccines before those strains arrive.

The relatively rapid emergence of multiple COVID-19 virus variants has baffled researchers because most coronaviruses don't mutate and evolve so quickly. That's because they possess a built-in "proofreading" mechanism to prevent mutations as they make copies of themselves while growing and multiplying in our cells.

But scientists at USC figured out the COVID-19 virus' strategy for bypassing the proofreading: It hijacks enzymes within human cells that normally defend against viral infections, using those enzymes to alter its genome and make variants.

According to lead researcher Xiaojiang Chen, professor of biological sciences and chemistry at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, the findings could prove vital to curbing the pandemic by helping to prevent new surges in infection caused by new variants.

"New strains can become increasingly more contagious and evade the existing vaccine's protection," Chen said. "Predicting new variants and preparing effective vaccines ahead of time could stop new variants before they spread."

The best offense is a good defense

Chen and the USC team infected human cells with the coronavirus in the lab and then studied changes to the virus' genome as it multiplied, making copies of itself, within the cells.

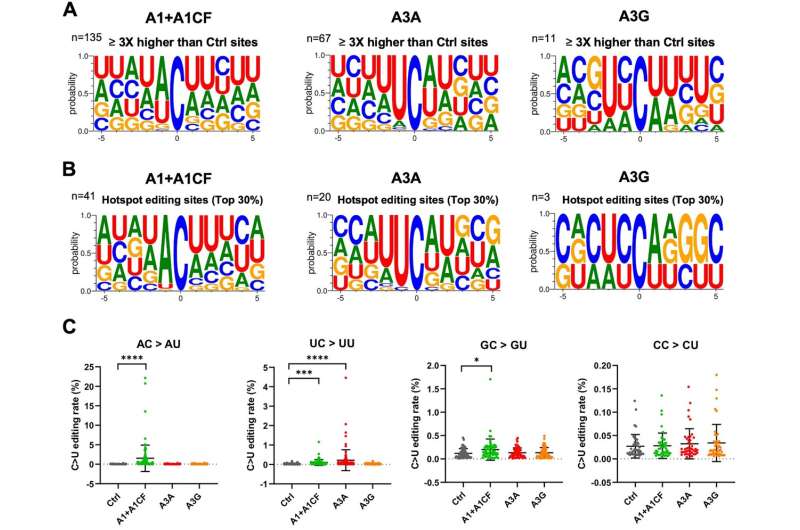

The genetic code sequence of the virus, which is composed of DNA's close cousin RNA, uses four letters to identify component nucleotides: A, C, G, U. During their analysis, Chen and the team noticed an interesting pattern: Many mutations that arose as the virus replicated itself were caused by changing one particular nucleotide in the code to another—the letter "C" changed to "U."

The high frequency of C-to-U mutations pointed them toward a group of enzymes that cells often use to defend against viruses. Called APOBEC, the enzymes convert Cs in the virus' genome to Us with the aim of causing fatal mutations.

But Chen and the team found that for the COVID-19 virus growing in the human cells, not only are the C-to-U mutations not fatal, they actually benefit the virus by providing a way for the virus to mutate, evolve and develop new strains faster than expected.

"We have provided the first experimental evidence that our own enzymes can help the COVID-19 virus to mutate quickly," Chen said. "Somehow the virus learned to turn the tables on these host APOBEC enzymes for its evolution and fitness."

Turning the tables back around

Fortunately for researchers looking to overcome COVID-19, every good offense has its weakness. In this case, the mutations created by APOBEC enzymes are not random—they convert C to U in specific places in the genetic sequence where a U or A is just ahead of the C (like UC or AC).

With this insight, scientists can look for every UC and AC in the COVID-19 virus genome and, using powerful computational and experimental methods, predict and test what will happen if any of them change to a U. This can help them predict what new COVID-19 variants might emerge and suggest how to update vaccines so they protect against any new variants that are likely to spread.

Chen and the team aim to do just that, studying what potential effects C-to-U mutations caused by APOBEC enzymes might have on the COVID-19 virus' life cycle and its ability to spread and cause disease. Over time, this information can help scientists produce new drugs and vaccines to defeat drug-resistant and vaccine-evading COVID-19 virus strains.

More information: Kyumin Kim et al, The roles of APOBEC-mediated RNA editing in SARS-CoV-2 mutations, replication and fitness, Scientific Reports (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-19067-x