This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Multiple periods of loneliness may add up to higher mortality risk

Working from well-established research on the detrimental health effects of loneliness, University of Michigan researchers set out to study whether feeling lonely multiple times through the years leads to more serious illness and higher mortality risk in mid to later life.

They found that, indeed, it did.

"Cumulative loneliness in mid- to later-life may be a mortality risk factor with a notable impact on excess mortality," according to research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study was led by Xuexin Yu, a doctoral student in epidemiology at U-M's School of Public Health.

"The focus on cumulative loneliness brings a new contribution to the field of loneliness research," said study senior author Lindsay Kobayashi, professor of epidemiology and global health and director of the Social Epidemiology of Global Aging Lab.

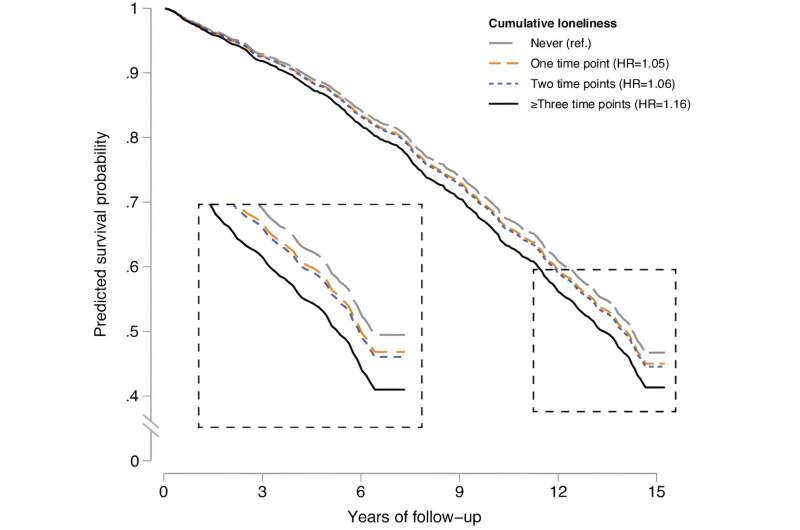

The researchers found that participants who reported more periods of loneliness had significantly greater mortality risk, compared to participants who reported no or fewer periods of loneliness. The team used data from more than 9,000 participants aged 50 and older in the U.S. Health and Retirement Study is considered the most authoritative data source on aging in the United States.

The data on loneliness covered an eight-year period from 1996–2004 and was categorized into four groups: never experienced loneliness and experienced loneliness at one, two, or three points. Responses were cross-referenced with participants' health and lifestyle and objectively measured social isolation at baseline in 1996 and subsequent mortality risk through 2019.

The results surprised even the researchers: They observed 106 excess deaths when loneliness was reported one time, 202 excess deaths when loneliness was reported two times, and 288 excess deaths when loneliness was reported three or more times over the eight-year exposure period.

"Loneliness is not a static experience; it is dynamic. So, the eight-year duration of our data on loneliness was a unique part of this study that allowed us to look into cumulative loneliness over time," Kobayashi said. "The numbers surprised me. They strike me as very high because loneliness is preventable. Anytime there are excess deaths due to a modifiable risk factor, it's too many."

With life expectancy in the U.S. still at historic lows and loneliness being treated as a global health crisis by the U.S. Surgeon General and the World Health Organization, the study urges prevention: "Loneliness may be an important target for interventions to improve life expectancy in the United States."

"Life expectancy in the U.S. has dropped. That is a particularly big red flag," Kobayashi said. "Reducing loneliness at a societal level is critical for older adults but also for younger individuals. There's increasing concern that as the population ages, loneliness will increase as the loss of meaningful roles in life comes to pass, such as leaving the workforce."

She says it's important to note that living alone or preferring solitude is not necessarily the same as feeling lonely.

"Even those who are socially isolated may not feel lonely. It's the feeling of loneliness, of needing people and purpose and not getting it, which appears to be bad for health," she said.

"As people age, they transition out of meaningful social roles. They need meaningful replacements. Maintaining integration with families is important and can be a big source of meaning in life. We do live in an individualist society and should evaluate our culture's value of older people to society."

Additional interventions to address the crisis of loneliness might be age-friendly communities and cities incorporating older people into urban planning, Kobayashi said.

"There are ways we can make environments accessible, offer places to go and socialize. It's about the physical design of communities and resources and priorities. It's about a cultural shift in how we see and portray older people." Kobayashi said. "Extending work life, especially as Baby Boomers age, could be of benefit. Policy changes are needed to support changes."

"These adaptations can promote community in general, something we've seen a loss of with the COVID-19 pandemic," she said. "This issue cuts across so many parts of society. It really does affect us all."

More information: Xuexin Yu et al, Association of cumulative loneliness with all-cause mortality among middle-aged and older adults in the United States, 1996 to 2019, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2306819120