This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Study suggests adolescent stress may raise risk of postpartum depression in adults

In a new study, a Johns Hopkins Medicine-led research team reports that social stress during adolescence in female mice later results in prolonged elevation of the hormone cortisol after they give birth. The researchers say this corresponds to the equivalent hormonal changes in postpartum women who were exposed to adverse early life experiences—suggesting that early life stress may underlie a pathophysiological exacerbation of postpartum depression (PPD).

The team's findings, published in Nature Mental Health, also suggest that current drug treatments for PPD in people may, in some cases, be less effective at targeting the relevant chemical imbalances in the brain, and that alternative methods may be more beneficial.

According to previous studies, an estimated one-third of psychiatric conditions fail to respond to current therapies, and "PPD is difficult to treat," says study senior author Akira Sawa, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Johns Hopkins Schizophrenia Center and professor of psychiatry, neuroscience, biomedical engineering, genetic medicine and pharmacology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "The new study results add to evidence that patients with PPD are not all the same, and more individualized diagnosis and treatment—a precision medicine approach—is needed."

PPD, states the federal government's Office on Women's Health, is estimated to occur in 7% to 20% of all women, most commonly within six weeks of giving birth. Symptoms include feelings of sadness, anxiety, and fatigue, and can make it difficult to complete basic self-care tasks and care for the new baby.

The current first-line treatment for PPD is the use of a class of anti-depressant pills called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), but these are only effective in approximately half of all patients. SSRIs boost the effects of the natural brain chemical serotonin, one of many hormone-like substances that help control mood. Some patients also are treated with IV infusions of a different class of drugs that target GABAA, a brain chemical linked to nerve hyperactivity.

However, the calming infusions are costly (more than $30,000 for a single course of one such drug) and often require hospitalization. They are generally reserved for the most severe and resistant cases of PPD.

In the new study, the Johns Hopkins-led research team aimed to build on evidence that adverse life events may affect the likelihood and severity of PPD. Previous studies have shown that PPD is more prevalent in teens, and in urban populations.

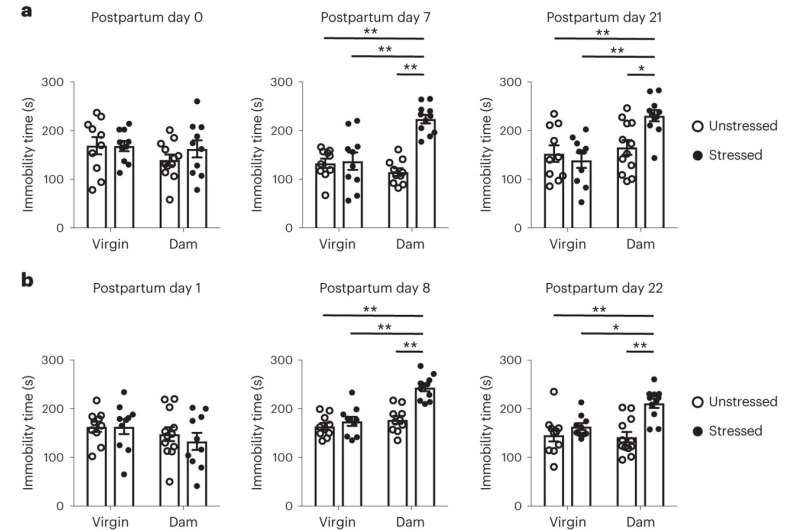

Working with mice, the researchers first created four test groups: unstressed virgins, stressed virgins, unstressed mothers and stressed mothers. The stressed mice were subjected to social isolation in their adolescence, and all groups were tested for stress. At seven days postpartum, the stressed mothers showed decreased mobility and a decrease in sugar preference, both of which are considered markers for depression. This persisted for at least three weeks after delivery.

As the second and most critical step, the researchers tested plasma levels of several hormones and found the level of cortisol was increased in mothers both with and without adverse early life experiences. However, cortisol levels in unstressed mothers decreased to normal levels after delivery, while the levels in mothers with adverse early life experiences remained high for one to three weeks after birth. This finding, Sawa says, suggests a correlation between prolonged post-delivery elevation of cortisol and behavioral changes in postpartum mice who experienced social isolation in adolescence.

If these findings translate to humans, it could mean that a different kind of antidepressant, a glucocorticoid receptor (GR) antagonist, which blocks the effects of elevated cortisol, could be a novel treatment option for PPD. Mifepristone may be one such drug.

"Unfortunately, everyone knows someone who has suffered or currently suffers from PPD, and it has such a huge impact on both mother and baby," says Sawa. "The alternative line of treatment suggested by the mouse study—where the findings are consistent with those from our observational study in humans—might enable mothers to be treated at home and avoid separation from their babies, and target a different mechanism for depression that may be specific to PPD."

Plans are underway, Sawa says, to collect precise data on cortisol levels in people with PPD to determine if GR antagonists would be more beneficial than current treatments for some, and later, to conduct clinical trials with alternatives to SSRIs.

More information: Minae Niwa et al, Prolonged HPA axis dysregulation in postpartum depression associated with adverse early life experiences: a cross-species translational study, Nature Mental Health (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s44220-024-00217-1