Investigators show how immune cells are 'educated' not to attack beneficial bacteria

An international research team led by Weill Cornell Medical College investigators has discovered an answer to why the human immune system ignores roughly 100 trillion beneficial bacteria that populate the gastrointestinal tract. The findings, published April 23 in the journal Science, advance investigators' understanding of how humans maintain a healthy gastrointestinal tract, and may provoke new ways to treat inflammatory bowel disease—including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis—whose origins have been mysterious and treatment difficult.

The investigators studied T cells—critical components of the adaptive immune system—which have the capacity to recognize, eliminate and remember foreign microbes that invade our bodies. T cells are named after the thymus, an organ where they develop and are taught not to attack normal human tissues and organs, leaving them free to target and eradicate disease-causing foreign invaders. One question that had puzzled scientists until now is how these cells learn to ignore beneficial bacteria in the intestine that are also foreign, but not harmful.

In the study, the research team discovered that once they leave the thymus, T cells are again educated in the gastrointestinal tract, or gut, to leave beneficial bacteria alone. This dual education strategy is vital to supporting healthy immune function, the investigators say. Disruption in the pathway that facilitates this education, they add, causes the immune system to attack beneficial bacteria in the intestine, which is often linked to the development and progression of diseases like inflammatory bowel disease, HIV, viral hepatitis, cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes and cancer. Therapeutic strategies to promote and boost the activity of this education pathway may be beneficial in treating patients with these chronic inflammatory disorders, the investigators say.

"In many chronic human diseases, the immune system attacks bacteria in the intestine that are normally beneficial. Although we do not yet know whether this is a cause or consequence of these complex diseases, experimental evidence suggests that this inflammatory process contributes to disease progression," says senior author Dr. Gregory F. Sonnenberg, an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology in medicine and a member of the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell. "Our study demonstrates that there may be an efficient way to eliminate pro-inflammatory T cells in the intestine that attack beneficial bacteria. This would not only help our patients with inflammatory bowel disease, but also might give us clues about how to treat other chronic inflammatory diseases caused by abnormal T cell responses, such as allergic and autoimmune disorders."

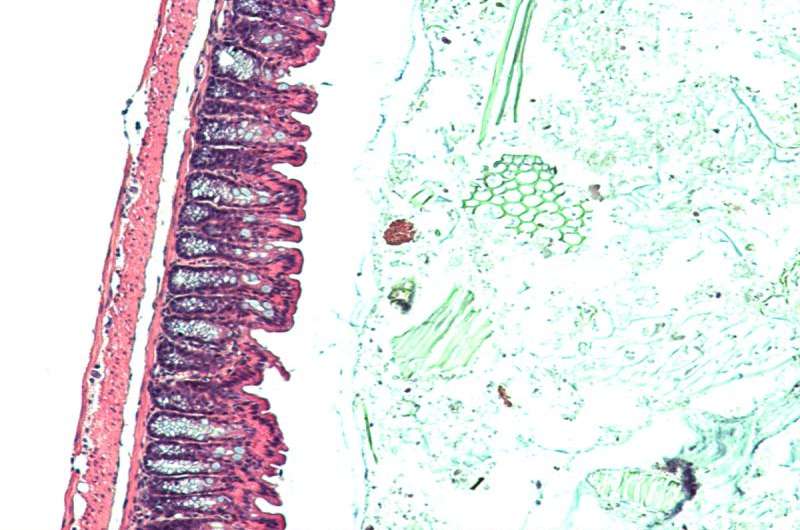

In earlier research, Dr. Sonnenberg and his team identified that a recently discovered member of the innate immune system—innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)—critically regulate immune cell interactions with bacteria. These ILCs, and other cells of the immune system, are found in the intestine, which is constantly exposed to and colonized by beneficial bacteria. "There is a physical separation between the immune system and most beneficial bacteria," Dr. Sonnenberg says.

The researchers had previously found that ILCs reinforce a physical barrier between the immune system and intestinal beneficial bacteria, but in this study, they uncovered a new key role for these cells—that they act like the cells in the thymus that educate T cells.

In a process that developed over evolution, bits of human tissues and organs are introduced to T cells in the thymus so they "know" what not to attack after leaving the organ. Specialized cells in the thymus teach T cells this behavior by interacting with a molecule known as the Major Histocompatibility Complex class II (MHCII). Any T cells with the potential to attack the human body and organs and cause auto-immunity are destroyed before they can leave the thymus. However, T cells with the potential to attack beneficial bacteria are not educated or eliminated in the thymus. It was therefore unclear what stopped these T cells from attacking beneficial bacteria in the intestine.

The scientists found a similar process happening directly within the GI tract, an organ that contains the majority of the body's total immune system.

"Due to the similarities of what we know happens in the thymus, we have called this new process 'intestinal selection,'" says first author Dr. Matthew R. Hepworth, a postdoctoral associate in medicine who works in Dr. Sonnenberg's laboratory. "ILCs also interact with T cells through MHCII machinery to educate T cells in the intestine.

"In the thymus, T cells are educated not to attack our organs," he adds, "and in the GI tract, using ILCs, they are further educated not to attack beneficial bacteria."

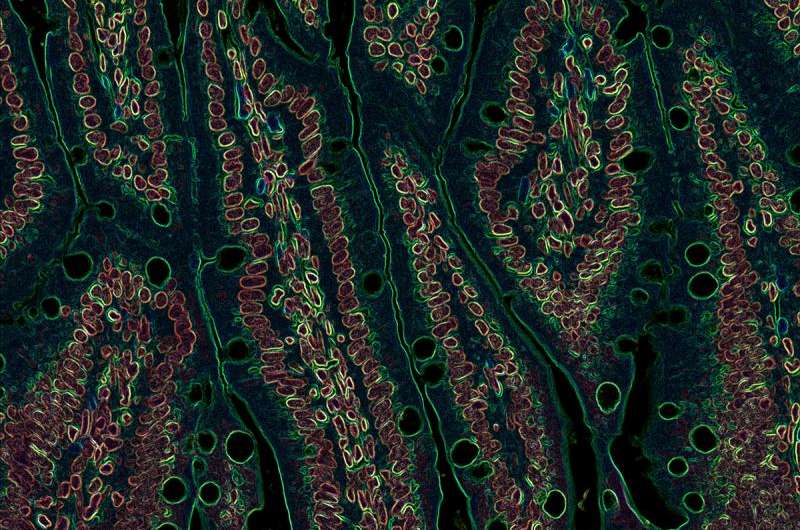

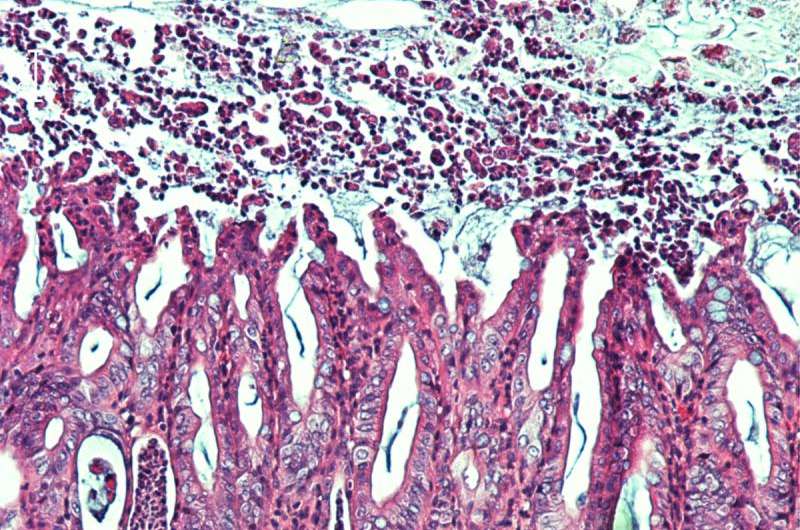

Using mice to test their findings, the researchers discovered that ILCs destroy T cells with the potential to attack beneficial bacteria, and that impairing ILC function led to severe intestinal inflammation. Then, with the help of researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, the team looked at intestinal biopsies of pediatric patients diagnosed with Crohn's disease, one of the major forms of inflammatory bowel disease.

"We found ILCs in intestinal biopsies from pediatric patients diagnosed with Crohn's disease, but they were not functioning properly because, in many cases, they were lacking MHCII machinery, so T cells were not educated to ignore beneficial bacteria," Dr. Sonnenberg says. "In fact, we found the loss of MHCII correlated with an increase in pro-inflammatory cells from matched biopsies of children with Crohn's disease. That tells us that this education process may be impaired in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, and that restoring adequate levels of MHCII might help to eliminate pro-inflammatory T cells and reduce chronic intestinal inflammation."

Dr. Sonnenberg says there are likely many causes of inflammatory bowel disease, and other pathways that help control T cells in the gut. "But our work shows a previously unrecognized pathway whereby ILCs educate our immune system not to attack beneficial bacteria," he says.

Dr. Sonnenberg, his laboratory and the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in IBD are now exploring how scientists can utilize this knowledge and design novel therapeutic strategies to boost MHCII on ILCs and limit chronic intestinal inflammation.

More information: "Group 3 innate lymphoid cells mediate intestinal selection of commensal bacteria-specific CD4+ T cells." Science DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa4812