The brain recruits its own decision-making circuits to simulate how other people make decisions

A team of researchers led by Hiroyuki Nakahara and Shinsuke Suzuki of the RIKEN Brain Science Institute has identified a set of brain structures that are critical for predicting how other people make decisions.

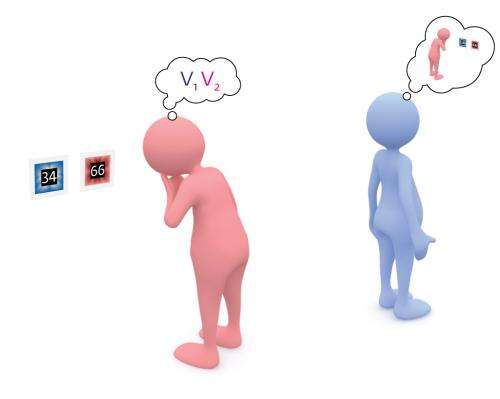

This phenomenon is thought to involve simulation learning, a process by which the brain generates a model of how another person will act by directly recruiting its own decision-making circuits. However, little else is known about the underlying brain mechanisms.

Nakahara and his colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging to scan participants' brains while they performed two simple decision-making tasks. In one, they were shown pairs of visual stimuli and had to choose the 'correct' one from each, based on randomly assigned reward values. In the second, they had to predict other people's decisions for the same task.

The researchers confirmed that the participants' own decision-making circuits were recruited to predict others' decisions. The scans showed that their brains simultaneously tracked how other people behaved when presented with each pair of stimuli, and the rewards they received.

Effective simulated learning occurs when the brain minimizes two different prediction errors—the discrepancies between its prediction of others' actions and the rewards they received and how they actually acted and were rewarded. The researchers found that each of these variables was associated with activity in a distinct part of the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

The bigger the prediction error in simulating other people's rewards, the more activity was observed in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) an area located at the base of the frontal lobe of the brain that is associated with decision making, while the larger the prediction error in simulating another's actions, the more active were the dorsomedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices.

The ability to attribute mental states to others is referred to as theory of mind, or 'mentalizing', and is widely thought to involve the PFC. This, however, is the first study to show that activity in the PFC encodes prediction errors of one's own rewards as well as those of the simulated decisions of other people, and that both of these signals are required for simulated learning. "We showed that simple simulation is not enough [to predict other peoples' decisions], and that the simulated other's action prediction error is used to track variations in another person's behavior," says Nakahara. "In real life, some people are similar to us but others are not. Yet, we still interact with different types of people somehow, and next we hope to understand how this is possible."

More information: Suzuki, S., Harasawa, N., Ueno, K., Gardner, J.L., Ichinohe, N., Haruno, M., Cheng, K. & Nakahara, H. Learning to simulate others' decisions. Neuron 74, 1125–1137 (2012). www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273%2812%2900427-8