Immune cell suicide alarm helps destroy escaping bacteria

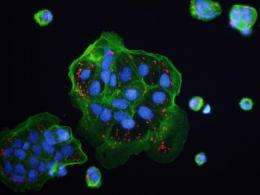

Cells in the immune system called macrophages normally engulf and kill intruding bacteria, holding them inside a membrane-bound bag called a vacuole, where they kill and digest them.

Some bacteria thwart this effort by ripping the bag open and then escaping into the macrophage's nutrient-rich cytosol compartment, where they divide and could eventually go on to invade other cells.

But research from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine shows that macrophages have a suicide alarm system, a signaling pathway to detect this escape into the cytosol. The pathway activates an enzyme, called caspase-11, that triggers a program in the macrophage to destroy itself.

"It's almost like a thief sneaking into the house not knowing an alarm will go off to knock down the walls and expose him to capture by the police," says study senior and corresponding author Edward Miao, PhD, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at UNC. "In the macrophage, this cell death, called pyroptosis, expels the bacterium from the cell, exposing it to other immune defense mechanisms."

A report of the research appears online in the journal Science on Thursday January 24, 2013.

Miao, also a member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, says the new findings show that having this detection pathway protects mice from lethal infection with the type of vacuole-escaping Burkholderia species: B. thailandensis and B. pseudomallei.

Both are close relatives. But they differ in lethality. B. pseudomallei is potentially a biological weapon. Used in a spray, it could potentially infect people via aerosol route, causing sickness and death. Moreover, it also could fall into a latent phase, "essentially turning into a 'sleeper' inside the lungs and hiding there for decades," Miao explains. In contrast, B. thailandensis, which shares many properties with its species counterpart, is not normally able to cause any disease or infection

These environmental bacteria are ubiquitous throughout S.E. Asia, and were it not for the caspase-11 pathway defense system, that part of the world could be uninhabitable, Miao points out.

This grim possibility clearly emerged in the study. Mice that lack the caspase-11 detection pathway succumb to infection not only by B. pseudomallei, but also to the normally benign B. thailandensis. "Thus caspase-11 is critical for surviving exposure to ubiquitous environmental pathogens," the authors conclude.

Miao points to research elsewhere showing that the pathway's abnormal activation in people with septic shock, overwhelming bacterial infection of the blood, is associated with death. "We discovered what the pathway is supposed to do, which may help find ways to tone it down in people with that critical condition.

As to bioterrorism, the researcher says it may be possible to use certain drugs already on the market that safely induce the caspase-11 pathway. "Since this pathway requires pre-stimulation with interferon cytokines, it is conceivable that pre-treating people with interferon drugs could ameliorate a bioterror incident. This could be quite important in the case of Burkholderia, since these bacteria are naturally resistant to numerous antibiotics.

"But first we have to find out if they would work in animal models, and consider the logistics of interferon stockpiling, which are currently cost prohibitive."

More information: "Caspase-11 Protects Against Bacteria That Escape the Vacuole", Science, 2013.