Engineers examine chemo-mechanics of heart defect

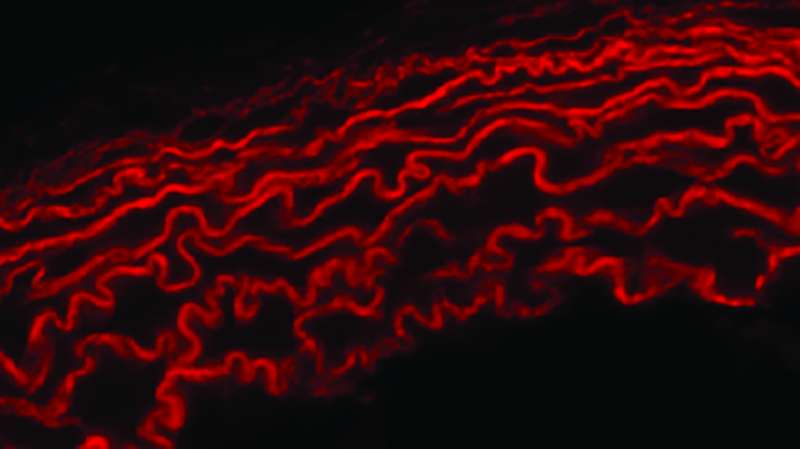

Elastin and collagen serve as the body's building blocks. They provide tensile strength and elasticity for a number of organs, muscles and tissues. Any genetic mutation short-circuiting their function can have a devastating, and often lethal, health impact.

For the first time, new research led by engineers at Washington University in St. Louis takes a closer look at both genetic and mechanical attributes, to better understand a disorder that affects how elastin and collagen function.

"Collagen and elastin are everywhere," said Jessica Wagenseil, associate professor of mechanical engineering & materials science at the School of Engineering & Applied Science. "They are in your blood vessels, your skin, your lungs. If they are not working properly, you can have problems in any of these organs."

Wagenseil's novel approach, recently published in Heart and Circulatory Physiology, focused on the genetic signaling and mechanical effects of mutations in lysyl oxidase, or LOX. LOX is a comprised of copper enzyme that cross-links collagen and elastin; a lack of the compound has been linked to aortic aneurysm risk in humans.

To learn more about exactly how LOX deficiency can lead to an aneurysm, Wagenseil and collaborators at Washington University School of Medicine examined tissue taken from mice born without LOX, and compared it to tissue taken from healthy mice. In the LOX deficient mice, they observed changes in mechanical behavior and in signaling of groups of genes that appeared to be a susceptibility differentiator in certain sections of tissue; the way they interacted seemed to provide some protection against aneurysm.

"We're really interested in how the cells respond to major changes in mechanics," Wagenseil said. "So when you take out this enzyme, and you have elastin and collagen that aren't cross-linked, they have totally different mechanical behavior. We expect to see those mechanical differences, but we found that there's this combination of the mechanics and the gene signaling that work together to lead to an aneurysm."

Wagenseil collaborated with Robert Mecham, Alumni Endowed Professor of Cell Biology and Physiology, and Professor of Medicine, Pediatrics and Bioengineering at the School of Medicine for the research.

"We're trying to understand signals that initiate aneurysms," Wagenseil said. "We examined the chemo-mechanical environment, looked at the two factors and how they worked in synch and changed together, which leads to the disease."

Wagenseil's next step: determining the role of inflammatory agents in LOX-deficient aneurysms.

More information: Marius Catalin Staiculescu, Jungsil Kim, Robert P. Mecham, Jessica Wagenseil "Mechanical behavior and matrisome gene expression in aneurysm-prone thoracic aorta of newborn lysyl oxidase knockout mice." Heart and Circulatory Physiology. May 26, 2017 DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00712