Putrid compound may have a sweet side gig as atherosclerosis treatment

Putrescine, the compound responsible for perhaps the foulest odor in nature—the smell of decomposing flesh—may also be a remedy for atherosclerosis and other chronic inflammatory diseases, according to a new study led by researchers at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

This unusual discovery stems from an investigation into the body's process for removing dead cells using macrophages, a type of white blood cell that digests dead cells.

"It's estimated that a billion cells die in the body every day, and if you don't get rid of them, they can cause inflammation and tissue death," says Ira Tabas, MD, Ph.D., the Richard J. Stock Professor of Medicine and professor of pathology & cell biology (in physiology & cellular biophysics) at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. "Removing these dead cells by a process called 'efferocytosis' (from the Latin 'to carry to the grave') is one of the body's most important functions."

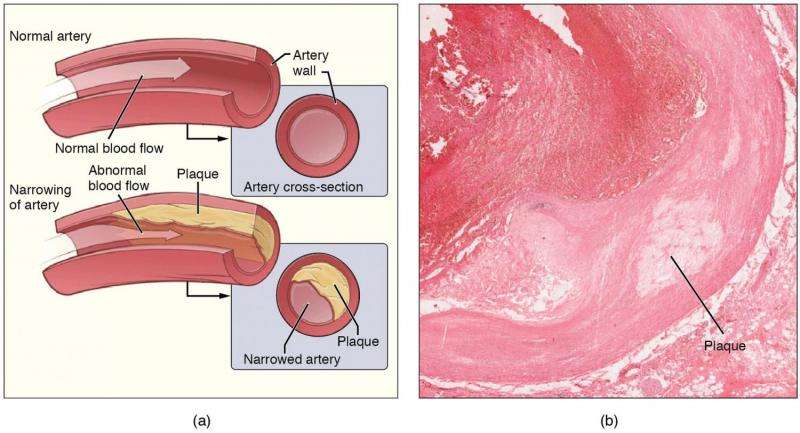

Normally, the process is initiated within minutes of cell death. However, studies have suggested that this essential housekeeping task is impaired in atherosclerosis, promoting the accumulation of plaques.

To learn more, Tabas, Arif Yurdagul Jr, Ph.D., associate research scientist in the Tabas lab, and colleagues set up human macrophages and dying cells in a dish and watched how the process unfolded.

That's when they detected the role of putrescine. Macrophages, they found, reclaim arginine and other amino acids from the dead cells they engulf and use an enzyme to convert arginine into putrescine. Putrescine then activates a protein (Rac1) that signals the macrophages to eat more dead cells.

The results suggested atherosclerosis may be partly a putrescine problem, so the researchers turned to mice with atherosclerosis to investigate.

The researchers found that mice with worsening atherosclerosis had a short supply of putrescine because they didn't have enough of a key enzyme (arginase 1) to make the compound. "But when we put putrescine in the animals' drinking water, their macrophages got better at eating dead cells and the plaques improved."

The findings suggest that putrescine could be used to treat atherosclerosis and other conditions characterized by chronic inflammation, such as Alzheimer's.

But who would want to take a medicine that smells like rotting flesh?

"Fortunately, when you dissolve putrescine into water, at least at the dosages needed to improve the plaques, it no longer gives off its odor. The mice drank it without any problem and show no signs of sickness," says Tabas, whose findings were published online Jan. 30 in the journal Cell Metabolism.

"Of course we do not yet know the feasibility and safety of using low-dose putrescine to ward off atherosclerotic heart disease and other diseases driven by defective efferocytosis. However, the study shows the potential of treating heart disease with compounds that help macrophages eat dead cells and that are currently in clinical trials for other indications."

The study is titled "Macrophage Metabolism of Apoptotic Cell-Derived Arginine Promotes Continual Efferocytosis and Resolution of Injury."

More information: "Macrophage Metabolism of Apoptotic Cell-Derived Arginine Promotes Continual Efferocytosis and Resolution of Injury," Cell Metabolism (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.01.001