Variants, boosters turn rich-poor vaccine gap into chasm

The global initiative to share coronavirus vaccines fairly already scaled back its pledge to the world's poor once. Now, to meet even that limited promise, COVAX would have to deliver more than a million doses every hour until the end of the year in some of the world's most challenging places.

That seems unlikely: Gavi, the vaccine alliance that helps run COVAX, warned in internal documents that a substantial number of doses might only show up in late 2022 or even 2023 as wealthy countries drag out their donations while locking in contracts for new shots by the hundreds of millions.

Even if the U.N.-backed initiative secured the doses and overcame the logistical hurdles, the developing world would still face a gaping need. COVAX's new promise is for 1.4 billion doses, but according to the documents, mid- and low-income countries need 4.65 billion to vaccinate 70% of their populations.

And that need is only expected to increase—as many countries pursue boosters and tweaked vaccines that can tackle new variants.

At this point more than half the world's population has received at least one shot, but only 6% of the population in the poorest countries have. Meanwhile, richer countries are pushing ahead with buying up third and fourth doses for their citizens.

COVAX was formed soon after COVID-19 became a pandemic, intended to guarantee that low- and middle-income countries would quickly get vaccine doses—without having to muscle their way into competitive markets with nations that could outbid them or be at the mercy of unreliable donations. Getting vaccines to every corner of the globe is especially important because experts say that until protection is broadly spread across the world, everyone remains at risk.

But COVAX lacked cash during the crucial months that the United States, countries in Europe and other wealthy nations locked in contracts. Its first delivery came Feb. 24—to Ghana—more than two months after injections started in Britain and the United States.

Poor countries fell further behind by the day, and COVAX was dealt a new blow in March when the Serum Institute of India, which was supposed to be its main supplier, cut off exports to boost domestic vaccine supplies amid a massive surge in coronavirus cases. Those exports are only now resuming.

In September, COVAX abandoned its initial goal to deliver 2 billion doses by the end of 2021, reducing it to 1.4 billion.

Gavi and the World Health Organization have trumpeted each donation pledge in bold headlines in news releases, while quietly burying the much smaller numbers of donated doses that are actually delivered.

"We have been vocal in calling out high income countries for hoarding vaccines and manufacturers for failing to prioritize COVAX, which represents a failure of multilateralism, not of COVAX, and I'm proud that COVAX has been able to make such a transformative impact in countries that otherwise would have been left out in the cold completely," said Aurelia Nguyen, its managing director.

But Gavi and WHO have both shied away from criticizing their biggest donor countries by name, even when they began vaccinating children or offering boosters to healthy adults—despite WHO's plea to countries to prioritize the world's poor over boosters and shots for kids at home. WHO's position on boosters could change depending on what's learned about omicron.

Despite the setbacks, in private briefings to partners ahead of a board meeting that ends Thursday, Gavi has consistently maintained that an increased vaccine supply in late 2021 would salvage their goals.

The hope was rich countries would wrap up their immunization campaigns in late 2021, and send more doses to the rest of the world.

That hasn't happened.

The push for booster shots in many wealthier countries presented the first obstacle—though it's not clear they make it impossible to keep promises. Rich countries pledged to donate 1.2 billion doses by mid-2022, and data from analytics company Airfinity from mid-October showed that those donations could go out this year and there would still be enough for boosters at home.

Now, manufacturers are looking at creating second-generation vaccines to tackle variants. Airfinity said that would take until late next year at best for a global rollout and would mean taking current vaccine production offline.

Not only that, but emerging preferences for certain shots—with better safety and efficacy profiles or easier transport requirements—undermined COVAX's hope to use a wide pool of WHO-authorized vaccines, including those made in China, Russia and India.

As COVAX transitions from emergency mechanism into longer-term effort, some public health officials want to abandon the model altogether.

"There hasn't been any admission of how badly they miscalculated things," said Kate Elder, senior vaccines policy adviser at Doctors Without Borders.

She explained that a significant proportion of COVAX doses are now based on donations, rather than the deals with pharmaceuticals the effort was banking on last year. That's because rich countries including Britain, Canada, Germany and others signed early deals with drugmakers that reserved the vast majority of the limited COVID-19 vaccine supply, cutting out COVAX. Meanwhile, their promised donations are only trickling in.

Sajid Javid, Britain's health minister, was asked about the discrepancy between rich and poor nations when it comes to vaccines and booster shots. He told Parliament on Monday that he and his counterparts among the G-7 wealthy nations understood the need to share with poor nations and had "all agreed about the importance of this and about redoubling efforts."

Four days later, the U.K. announced it had sealed deals into 2023 to offer Britons fourth doses.

"I don't know if there's a way to make governments not hoard vaccines, so maybe we need a way to force them to donate a certain percentage instead," Elder said.

Although COVAX has now revised some of its initial practices, little has been changed about the effort's fundamental structure.

But Dr. Madhukar Pai, of McGill University's School of Population and Public Health, said the blame primarily rests with governments of wealthy countries that are ignoring basic public health tenets.

"It's almost as if they've decided their main strategy for pandemic response is to purely protect themselves with more and more doses and to close borders to anyone who might bring the virus in. This is primitive thinking," Pai said. "The amount of money that would be required to vaccinate the whole world, and if you compare it with the carnage, the lives lost, the economic loss. … It's the deal of the century."

-

Kenyans line up to receive a dose of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine manufactured by the Serum Institute of India and provided through the global COVAX initiative, at Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi, Tuesday, April 6, 2021. COVAX, created to share coronavirus vaccines fairly, already scaled back its pledge to the world's poor once. Now, to meet even that limited promise, it would have to deliver more than a million doses every hour until the end of the year. Credit: AP Photo/Brian Ingasnga, File -

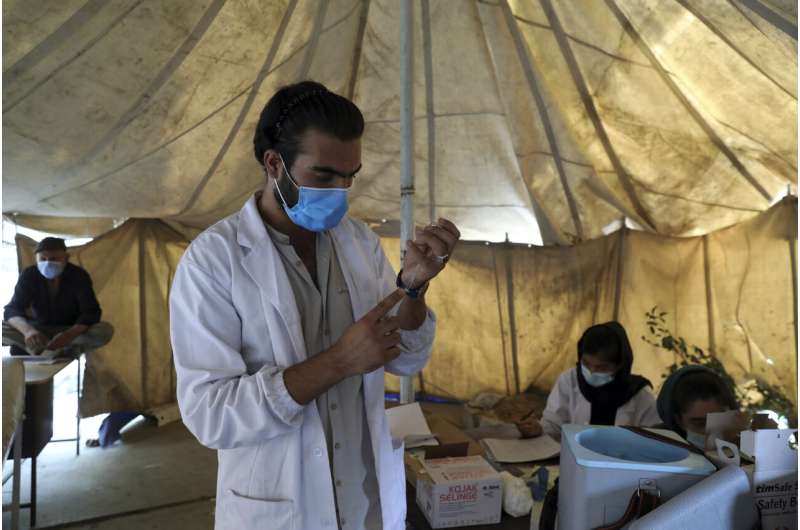

Residents wearing face masks to help curb the spread of the coronavirus line up to receive the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine donated through the U.N.-backed COVAX program at a vaccination center in Kabul, Afghanistan, July 11, 2021. COVAX, created to share coronavirus vaccines fairly, already scaled back its pledge to the world's poor once. Now, to meet even that limited promise, it would have to deliver more than a million doses every hour until the end of the year. Credit: AP Photo/Rahmat Gul, File

In a statement last week, Gavi applauded Switzerland's decision to cede its place to COVAX in the queue to obtain Moderna vaccines.

That would mean COVAX will get 1 million doses later this year—putting it nearly an hour closer to its goal.

© 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.