HIV uses host cell's own 'emergency' response for replication, says researcher

Researchers at the University of Missouri and the University of Minnesota have discovered how HIV evades one of the body's best defenses—and their collaborative work could offer hope for future treatments that stop the spread of HIV in the body.

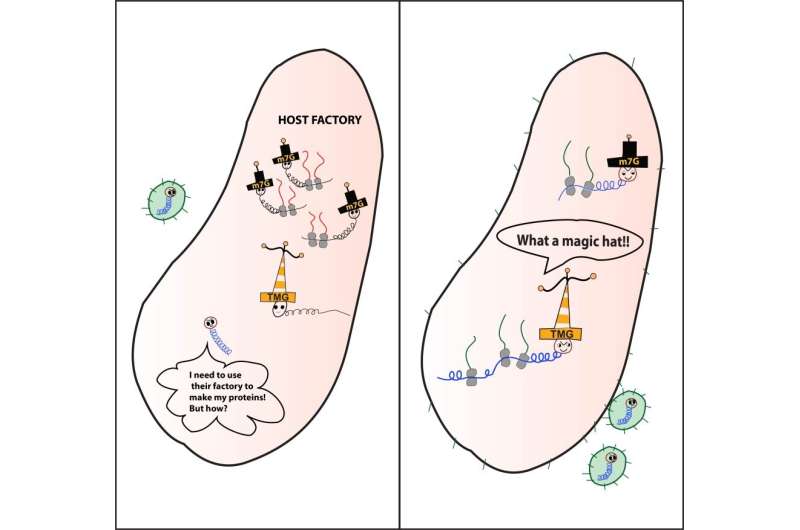

Messenger RNA (mRNA) from HIV is known to utilize a host cell's system in order to create its own viral proteins. In response, the infected cell shuts down the infiltrated pathway. But despite these roadblocks, HIV is still able to replicate itself and spread. Researchers and scientists have long struggled to determine how HIV accomplishes such a seemingly impossible trick.

Xiao Heng, associate professor of biochemistry at MU, was among the collaborators who discovered that after global mRNA translation pathways (tools that allow a cell to replicate) are shut down, HIV can impersonate the stress response of the host. This disguise helps it gain access to emergency translation pathways—essentially offering forged credentials. These forged credentials allow HIV into "restricted" areas of the cell so that it can continue producing its own viral proteins.

"When the host cell recognizes HIV, it will stop dividing and just maintain survival," Heng said. "In response, HIV learns from the host and uses the way cells react when they are stressed."

After infection, HIV attacks white blood cells within the immune system. These cells will stay infected for the rest of a patient's life. If untreated, HIV can develop into AIDS.

"AIDS has been around for almost four decades, and early on we were always talking about new antiviral therapeutics—but we still have 38 million people living with AIDS," Heng said. "If we're able to identify and stop or medically disrupt this process, we might be able to regulate HIV going forward."

To help illustrate their findings, Heng brought the research to a group of third-, fourth- and fifth-grade students in Columbia, Missouri. After discussing her work and answering questions, she asked students to draw what they imagined the process looked like inside a cell. Their creativity offered Heng another way to describe these complex functions.

"The virus needs to use the host's own factory to replicate," she said. "But cells recognize it as an intruder and shut down the factory. Then HIV has to find a way to produce its own necessary protein. So, HIV is able to disguise itself using a different 'hat' that allows it access to use the host emergency pathways. This permits it to make its own proteins, package itself and infect other cells."

Heng is hopeful their discovery can be used to develop new, more effective treatments for HIV, including one day finding a cure.

More information: Gatikrushna Singh et al, HIV-1 hypermethylated guanosine cap licenses specialized translation unaffected by mTOR, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2021). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2105153118