This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Cancer researchers discover mechanisms that restrain oncogene-expressing cells

To form a cancer, cells need to accumulate oncogenic mutations that confer tumor-initiating properties. However, recent evidence has shown that oncogenic mutations occur at a surprisingly high frequency in normal tissues, suggesting that mutations alone are not sufficient to drive cancer formation and that other mechanisms should promote or restrain oncogene-expressing cells from progressing into invasive tumors.

In a study published in Nature, researchers led by Prof. Cédric Blanpain, MD/Ph.D., investigator of the WEL Research Institute, Director of the Stem Cells and Cancer Laboratory and Professor at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, discovered the mechanisms that restrain oncogene-expressing cells to give rise to invasive tumors.

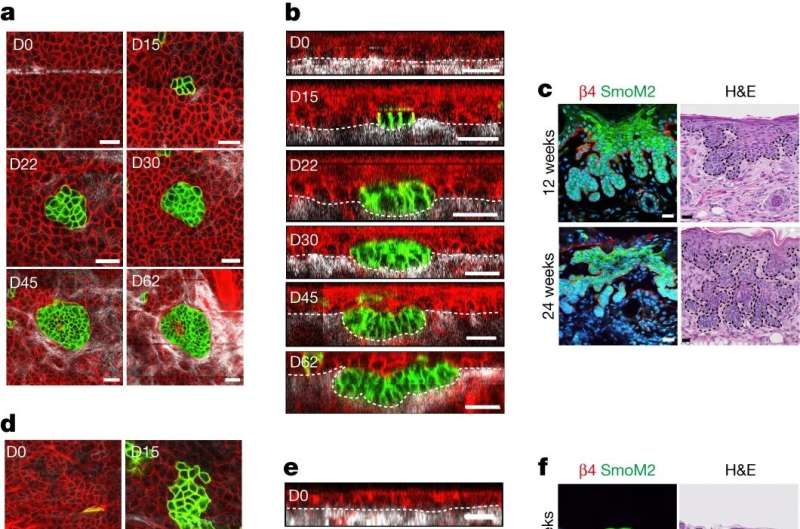

Using multidisciplinary approaches combining lineage tracing, clonal analysis in living animals using intravital microscopy, single cell sequencing, and functional experiments, Nordin Bansaccal and colleagues have investigated the ability of oncogene-expressing cells in different skin locations to develop basal cell carcinoma (BCC), the most frequent cancer in humans at a single cell resolution.

Analysis of oncogene-expressing cells over time in the ear and back skin reveals a very different outcome. In the ear, oncogene-expressing cells expand laterally during the first month and then grow vertically and invade the underlying dermis giving rise to the typical appearance of invasive BCC. Interestingly, and in sharp contrast with the ear, in the back skin, oncogene-expressing cells expand laterally and are not able to invade the dermis, but instead continue to expand laterally without giving rise to tumor formation.

These data demonstrate that the inability of the back skin epidermis to give rise to skin tumors is not related to the inability of the oncogene targeted cells to divide and expand, but rather is the consequence of their inability to switch from lateral expansion to vertical invasion.

As mutated clones expand over time, they must compete for space with their normal neighboring cells. In the ear epidermis but not in the back skin, there is a strong mechanical constraint at the border between oncogene-targeted cells and the normal cells that restrain lateral expansion and promote vertical growth. Several mechanisms of cell competition have been described including induction of cell death or terminal differentiation.

Bansaccal and colleagues found that oncogene-expressing cells present different abilities to compete with normal cells depending on their body locations.

"As cell competition was thought to be essential for tumor formation, it was really surprising to find that oncogene-expressing cells in the back skin are much more efficient to induce cell competition as compared to the ear epidermis and explain why oncogene-expressing cells can expand horizontally in the back skin without necessarily being associated with tumor invasion. Our findings that oncogene-induced cell competition does not necessarily lead to tumor initiation can explain why oncogene-mutated cells can be found in normal human tissues without any signs of cancer," explains Nordin Bansaccal, the first author of the paper.

Single-cell molecular analysis showed that cells in the back skin and the ear are very similar in normal conditions. However, following oncogene expression, cells of the ear but not of the back skin undergo a profound reprogramming into an embryonic-like state. As the cells were very similar before oncogene expression, the team investigated whether the mechanisms that constrain tumor development are related to the extracellular environment.

They found that the composition of the underlying extracellular matrix was very different in the susceptible and resistant parts of the skin. The part of the skin that are resistant to tumor initiation present an abundant and thicker collagen network associated with an increase in the stiffness of the underlying extracellular matrix.

By enzymatically decreasing collagen density, Bansaccal and colleagues demonstrate that the abundance of collagen was a key factor in restricting the invasion and tumor formation in the back skin. Aging and UV exposure are also associated with decrease in collagen density in the skin. Interestingly, oncogene expression in old mice or following UV exposure, leads to skin tumor formation in the back skin, demonstrating that the level of collagen expression dictates the competence for skin tumor initiation.

"Our study demonstrates that the composition of the extracellular environment regulates the regional competence to undergo tumor initiation and invasion. Our data are relevant for understanding the formation of human skin cancer, as BCC preferentially arises from certain body locations such as the ear and nose that present different collagen abundance, chronic sun exposure is one of the most important risk factors for BCC formation and BCC preferentially develops in older humans. Future studies will be important to identify in other tissues the factors that promote or restrict tumor formation, possibly leading to new prevention strategies to decrease cancer formation," says Cédric Blanpain, the director of this study.

More information: Cédric Blanpain, The extracellular matrix dictates regional competence for tumour initiation, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06740-y. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06740-y