This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Investigating the smallpox blanket controversy

In Indian Country, it is an accepted fact that white settlers distributed items, such as blankets contaminated with smallpox and other infectious diseases, aiming to reduce the population of Native people resisting their Manifest Destiny. These accounts have left a legacy of trauma and distrust in Native communities that persist to this day. It comes as quite a surprise to Indigenous people to learn that a controversy exists regarding the veracity of these events. This article aims to answer some of the lingering questions while shedding light on the controversy.

What made smallpox so infamous?

Smallpox is a highly contagious disease caused by the variola virus in the Orthopoxvirus family. It is widely considered one of the deadliest viruses in human history. Smallpox-like rashes on Egyptian mummies suggest that it existed with humans for at least 3,000 years. In the 20th century alone, smallpox is estimated to have killed 300 million people.

Smallpox symptoms

The first symptoms of smallpox disease are fever, headache and fatigue lasting 2-4 days. After the onset of symptoms, a characteristic rash appears and develops in stages, beginning in the mouth and expanding to cover the whole body. Eventually, the bumps scab over and fall off, leaving very visible scarring. Victims remain contagious until the last scab falls off (~3-4 weeks after onset).

Types of smallpox

There are 2 recognized forms of smallpox, variola minor and variola major, which carry mortality rates of 1% and 30%, respectively. In addition, there are 4 clinical presentations of the disease: ordinary, modified, flat and hemorrhagic. Historically speaking, ordinary (variola major) and modified-type smallpox were the most frequent infections and had the lowest mortality rates. Modified-type smallpox occurred in previously vaccinated people and produced a less severe rash than ordinary smallpox.

For reasons that are not completely understood, children and pregnant people were most likely to be afflicted with the variations. Flat-type (malignant) smallpox occurred more often in children and was nearly always fatal. In this form, the bumps from the rash merged and never filled with fluid. Hemorrhagic smallpox mainly occurred during pregnancy and was almost always fatal. The rash did not harden, but the skin underneath bled, causing it to look burnt. This was accompanied by internal bleeding and organ failure.

Identification of smallpox

The unique and easily recognizable rash caused by smallpox makes it easy to identify. Approximately 65-80% of survivors are afflicted with lifelong severe pockmark scarring. Other complications include miscarriage, blindness, opportunistic infection, arthritis and encephalitis. These created lifelong physical and psychological suffering for survivors.

Smallpox eradication

The first ever vaccine was created to prevent smallpox when Edward Jenner noted that milkmaids did not develop the disease after exposure to cows infected with the related virus, cowpox. For this reason, the word vaccine derives from the Latin word for cow, vacca. After monumental international vaccination efforts over many years, smallpox was officially considered eradicated in 1980. Before eradication, smallpox was an effective physical threat and served as a terrifying psychological weapon throughout history.

People in the 18th and 19th centuries may not have known what a virus was, but it was common knowledge among Europeans that smallpox spread after contact with a sick individual, and quarantine was the best strategy to reduce the spread. When smallpox swept through Indigenous communities, the aftermath was catastrophic. Devastating mortality rates included 38.5% of Aztecs; 50% lost in the Piegan, Huron, Catawba, Cherokee and Iroquois Nations; 66% of Omaha and Blackfeet; 90% of the Mandan, and the Taíno all but disappeared.

Why did smallpox have such a devastating effect on Native American populations?

One explanation for the catastrophic effect of European infectious diseases on Indigenous people originates with differences in societal evolution between the Old and New Worlds. While the relationships among humans, their environment and emerging infectious diseases are complicated, zoonotic pathogens make up 58% of human-infecting pathogens.

According to a 2022 study, many of the most devastating diseases for Indigenous people in the Americas originated with domesticated animals, and although there is no evidence of nonhuman reservoirs for smallpox, the disease is thought to have evolved from horses. Furthermore, because horses were not domesticated in North or South America prior to the arrival of the European settlers, the disease was one that Indigenous people did not have prior exposure to.

Studies have shown that host-pathogen coevolution promotes both general and specific resistance to pathogens and improves host immune responses to non-native and emerging threats. Agricultural settlements encroach on natural ecosystems, increasing interaction between species, and providing opportunities for zoonotic pathogen emergence. However, because farming and urbanization took a vastly different form in the Americas with few domesticated animal species, there were fewer immune system development opportunities.

By the time the Indigenous people were first exposed to smallpox, variola had evolved to only spread from human contact. The higher levels of susceptibility experienced by Native Americans to European diseases were evident to the colonists throughout the Americas. To King James I, the deaths demonstrated God's will that the territories "deserted as it were by their natural inhabitants, should be possessed and enjoyed by our subjects."

This opinion may not have been universal, but it does reflect a complete lack of concern for the previous inhabitants of the land.

Who writes history?

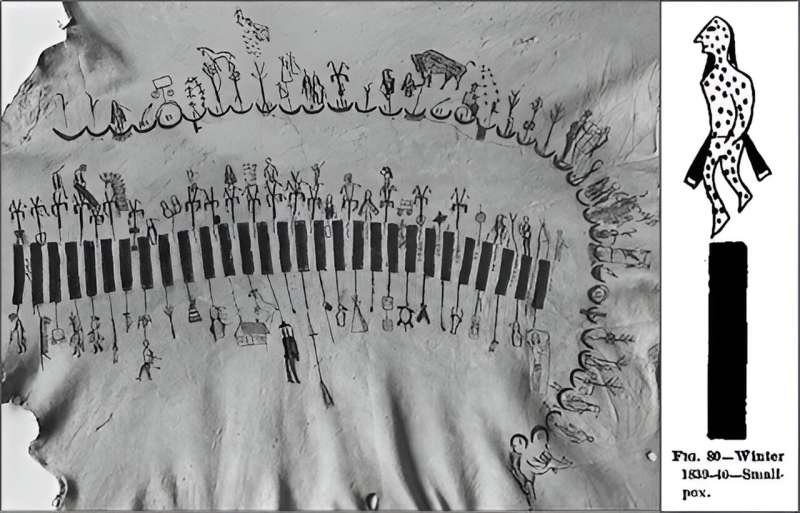

For Native American tribes, oral storytelling and pictographs were the only ways that knowledge was passed down. Until Sequoyah created the Cherokee syllabary in the early 19th century, none of the North American tribal languages had a written form. Thus, 18th- and 19th-century records are vastly biased toward European settlers. There are numerous accounts of intentional smallpox infection that come from Native voices, but extraordinarily little concrete evidence remains.

Examples of gifts from white settlers preceding outbreaks occurred throughout South America and North America. Incan history includes an account of their king receiving a box of paper scraps from the Spanish that was shortly followed by a smallpox outbreak. The Ottawa Tribe suffered an outbreak after receiving a gift from the French in Montreal with the injunction not to open the box until they arrived at home. The box contained only other boxes and "mouldy particles."

Yet, the most infamous records of intentionally spreading smallpox to Native Americans occurred in 1763 at Fort Pitt (present day downtown Pittsburgh). On June 24, 1763, William Trent, a fur trader commissioned at Fort Pitt, wrote in his journal after a failed negotiation between the British and the Delaware tribe. He stated that they had given the emissaries food, and as Trent wrote, "Out of our regard to them we gave them 2 Blankets and an (sic) Handkerchief out of the Small pox (sic) Hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect."

Later that year, the Delaware, Shawnee and Mingo Tribes laid siege to Fort Pitt. The fort's commander wrote to his superior officer, Colonel Bouquet, that he feared the disease would overwhelm the fort's inhabitants. After hearing of the outbreak, Bouquet's superior officer, Lord Jeffrey Amherst, sent a suggestion from New York: "Could it not be contrived to send the Small Pox (sic) among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians? We must, on this occasion, Use Every Stratagem in our power to Reduce them."

Bouquet responded, "I will try to inoculate [them] with some blankets that may fall in their hands and take care not to get the disease myself." It is important to understand that before Jenner's safer practice of vaccination, the term inoculation specifically meant deliberate infection. While this method was the main way of producing mass immunity, it was also known to be just as likely to start an epidemic as to end one. The timing of an outbreak of the virus that struck the Ohio Valley later that year and lasted well into 1764 coincides very closely with the distribution of infected articles from Fort Pitt.

Is it possible to spread smallpox with blankets?

In the early rash stage of smallpox disease, the variola virus is spread through exposure to droplets from coughing or sneezing. In later stages, the virus could be spread through contact with contaminated objects, like clothing and bedding. While the most contagious period is the early rash stage when mucous membranes in the mouth and throat are heavily infected with viral particles, face-to-face contact is not the only way to acquire the disease. Viable virus particles remain in urine, scabs, lesion fluid and saliva, which could linger on linens or other objects. Documented outbreaks occurred from contact with the dirty linen of smallpox patients, indicating that blanket transmission is possible.

Was the great plains outbreak of the 1830s intentional?

Seventy years after the 1764 Ohio Valley outbreak, Isaac McCoy was surveying the land in present-day Kansas and Oklahoma during a massive outbreak of smallpox on the Great Plains. The loss of life was staggering. The Pawnee population, for example, was reduced almost 50%. A reformer at heart, McCoy felt strongly that much of the suffering among Native American tribes was the direct result of the actions of white settlers.

Corresponding with President Andrew Jackson, McCoy detailed the effects of the outbreak on the Native Americans and implored Jackson and his Secretary of War, Lewis Cass, to provide aid. In a letter to President Jackson, he wrote, "In 1831, some of the white men… under the influence of a disposition, which it would seem had its origin in a world worse than ours, conceived the design of communicating the small-pox (sic) to those remote tribes! I have in my possession the certificate of a young man who was employed as one of the company; that they designed to communicate [smallpox] on a present of tobacco…or if such an opportunity should not offer, an infected article of clothing…Not long after this the Pawnees on the Great Platt River were most dreadfully afflicted with small-pox."

What happened to Isaac McCoy's proof?

This information was shared by Dr. Hugh Foley at Rogers State University. The previous letter is located in McCoy's book, History of Baptist Indian Missions. However, the book does not include the certificate of proof.

In search of McCoy's certificate, Foley checked the Kansas Historical Society, the Department of War, the Andrew Jackson libraries at the University of Tennessee and at Jackson's home, the Hermitage. The Library of Congress and the National Archives, as well as the Lewis Cass collections at the University of Michigan, the Detroit Public Library and the Cass collection at the National Archives were also searched. Many of these collections contained McCoy's correspondence with Jackson, but none of them contained his enclosed proof. What happened to this enclosure (and why it was removed) is likely long lost to history, and these questions may never have answers.

Where do we go from here?

Concrete proof is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain centuries after an event. This is particularly true when participants have caused the level of suffering and death commensurate with the elimination of entire villages or whole tribes of people. Native American populations are estimated to have declined more than 90% in the years since contact with Christopher Columbus, not only through disease but also through violent means.

While not every smallpox outbreak was deliberately caused by white settlers, enough evidence exists to clearly demonstrate that more than once actions were taken to intentionally facilitate its spread. In many of these cases, through their own words, people demonstrate depraved indifference, if not intentional genocide.

In December of 1775, at the siege of Boston during the American Revolutionary War, George Washington wrote in a letter to John Hancock that he must credit the rumors of the British military deliberately starting a smallpox outbreak; something he had previously believed unthinkable.

This begs the question: If one were willing to take such measures against citizens that they claimed were their own, and who had previously been friends, what was to stop them from doing the same thing to people they considered subhuman?