This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

New imaging software improves lung diagnosis for 30% of patients who can't tolerate contrast dye

For up to 30% of patients who are allergic to medical contrast dye or have a dye restriction because of other health conditions, they might find that it takes longer to get a diagnosis when it comes to life-threatening lung issues such as pulmonary embolism. That's because imaging methods that detect lung problems but don't use contrast dye aren't as accurate and can be more time-consuming to administer.

Now, new imaging software, developed by pulmonologist Girish Nair, M.D., with Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan, and biomedical engineer Edward Castillo, Ph.D., with The University of Texas at Austin, is addressing the industry-wide issue and giving patients a more reliable alternative with faster, more up-front diagnoses.

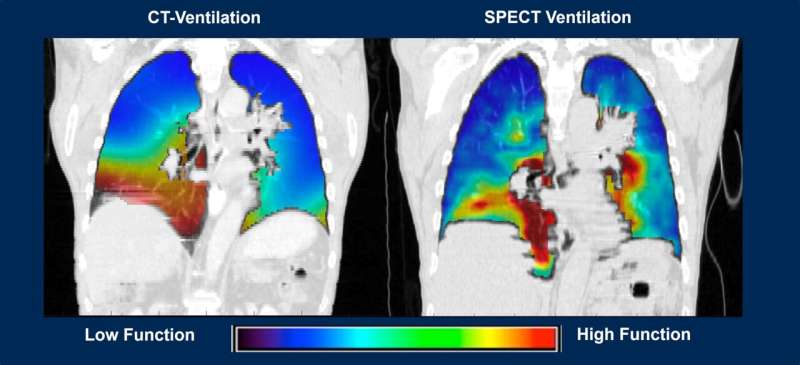

CT-Derived Functional Imaging, or CTFI, is a computed-tomography software program that takes complicated math, puts it into a formula called the Integrated Jacobian Formulation and quickly calculates major changes in lung volume as a patient breathes in and out. The method also measures changes in blood mass as a patient inhales and exhales while in a relaxed state, and blood is pumped into the lungs.

As a result, the software program helps doctors and researchers get consistent patient data, leading to better diagnoses and specifics on where to target potential therapies—all without contrast dye.

But it's not just helping those who can't receive contrast dye—it's also helping all patients with lung issues such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, and cancer.

"Up until now, a major problem with lung volume estimations from inhalation and exhalation CT scans were that results couldn't be replicated for individual patients," Dr. Nair said. "In other words, if you do a CT scan to calculate volume differences in the lungs the first time and then you try to do it again, you get different results every time for the same patient, making diagnosis and treatment harder.

According to Nair, radiation oncology is one area where accuracy is vital when treating a cancerous tumor in the lungs.

"Directed radiation to treat a tumor is essential and if the patient is breathing in and out, then the tumor will naturally move or change position," Dr. Nair said. "This can result in the radiation going into other areas of the lung and potentially causing more harm than good."

Using this newest software technology, the researchers have shown that they can avoid or limit radiation to normal areas of lung that may be next to a tumor during therapy. They've also found that using the software can help doctors detect pulmonary embolism by measuring and finding blood mass changes with a simple non-contrast, inhalation and exhalation CT scan.

"This is important because normally when you can't inject contrast dye, patients are either treated observationally with drugs that typically reduce the risk of blood clots but carry a risk of bleeding or have to undergo nuclear scans which are time-consuming and may include the injection of a radioactive drug or inhalation of certain type of gas," Dr. Nair said. "Our method is easier and doesn't involve either of these."

But the benefits of this software don't stop there.

New results are being presented at ATS 2024 showing how this new imaging software can predict disease progression for COPD patients over a 10-year period, something current technologies have not been able to do as well.

In a retrospective analysis of a prospective cohort including 8,583 COPD patients, the research team found that they could: improve the prediction model of patients at risk of dying based on inhalation-exhalation CT scan results obtained at baseline/enrollment; show disease progression in patients undergoing treatment and determine if the therapy is working; phenotype patients who might be at a higher risk of disease progression.

Currently, Castillo and Nair are leading a team of researchers looking at how a CTFI-based machine learning model with CT scans can increase accuracy and continue to help physicians better identify patients at risk of disease progression and improve COPD survival rates.

"Ultimately, the goal is always to ensure doctors have the best tools available to them when treating patients," Dr. Castillo said. "AI has the potential to further our work significantly in order to improve patient health and save lives."