This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

proofread

Better cancer trial representation begins with speaking one's language

Underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority populations in cancer clinical trials persists partly because translation and interpretation services and resources are unavailable or inadequate in the United States, according to a Children's Oncology Group (COG) study led by Columbia University School of Nursing. The updated study was published online in JNCI Cancer Spectrum on July 25, 2024 and will appear in the August 2024 journal issue.

In 2019, 68 million people in the United States were reported to speak a language other than English at home. In May 2023, the National Institutes of Health passed the Clinical Trial Diversity Act to enhance the inclusion of women, racially/ethnically diverse individuals, and people of all ages in NIH-funded research, building on 1994 legislation. Despite recent trends and policies, disparities remain.

"Appropriate representation of minoritized and underrepresented populations in clinical research, including persons who do not speak English, is necessary to ensure equitable access to novel treatments and generalizable research findings," Columbia Nursing Assistant Professor Melissa Beauchemin, Ph.D., the study's lead author, and her colleagues state in their report.

To understand the extent of translation and interpretation challenges that organizations face, Beauchemin and her colleagues within the Language Equity Working Group of COG's Diversity and Health Disparities Committee surveyed 230 COG-affiliated institutions. They found:

Full consent form translation was required at only 50% of institutions.

Twelve percent of institutional review boards restricted the use of centrally translated consent forms.

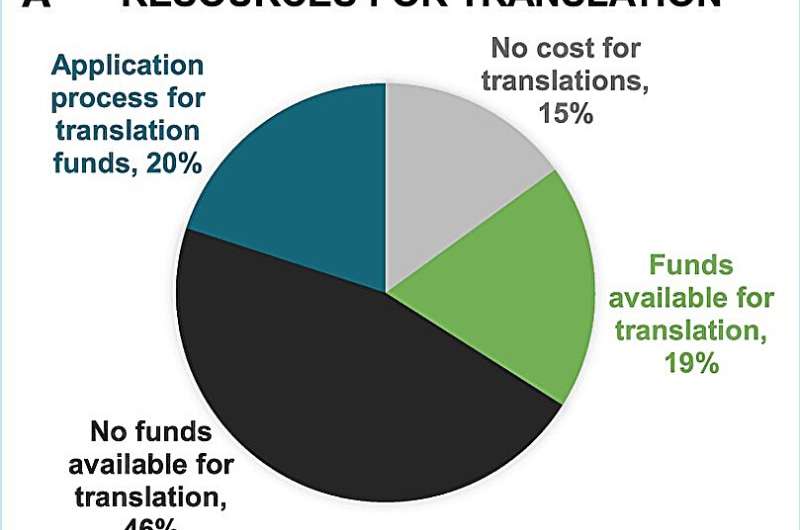

Forty-six percent of institutions reported insufficient funding to support translation costs; only 15% had access to free translation services.

Forty-four percent were required to use in-person interpreters for consent discussions; lack of available in-person interpreters was the most-cited barrier to obtaining consent.

"These findings show that there are multiple language-specific barriers that make it difficult to recruit people who do not speak English. Eliminating these may be the key to making clinical trials more accessible and universally applicable, while potentially impacting and improving outcomes," says Beauchemin.

More information: Melissa P Beauchemin et al, Clinical trial recruitment of people who speak languages other than English: a Children's Oncology Group report, JNCI Cancer Spectrum (2024). DOI: 10.1093/jncics/pkae047