New neural mechanism is found to regulate the chronic stress response

In addition to the classic stress response in our bodies - an acute reaction that gradually abates when the threat passes - our bodies appear to have a separate mechanism that deals only with chronic stress. These Weizmann Institute of Science findings, which recently appeared in Nature Neuroscience, may lead to better diagnosis of and treatment for anxiety and depression.

Dr. Assaf Ramot, a postdoctoral fellow in Prof. Alon Chen's group in the Weizmann Institute's Neurobiology Department, led the research pinpointing a small, previously unknown group of nerve cells in the paraventricular nucleus, or PVN, within the hypothalamus - a part of the brain involved in regulating many of the body's reactions. These cells' position in the PVN led the researchers to suppose that the nerve cells play a role in the stress response.

Chen explains that in the well-known stress response, the neurotransmitter CRF is released from the PVN and goes to the pituitary. The pituitary releases hormones that then cause the adrenal gland to flood the bloodstream with the "stress hormone" cortisol. Cortisol, along with the regular stress response, lowers the production of CRF, thus causing a negative feedback loop in which the mechanism slows down and stops.

The newly-discovered nerve cells express a receptor, CRFR1, on their outer walls, which enables them to take in the message of the CRF neurotransmitter. The experiments showed that in mice the cortisol actually increases the number of CRFR1 receptors on these nerve cells, suggesting a positive feedback loop that could be self-renewing, rather than abating.

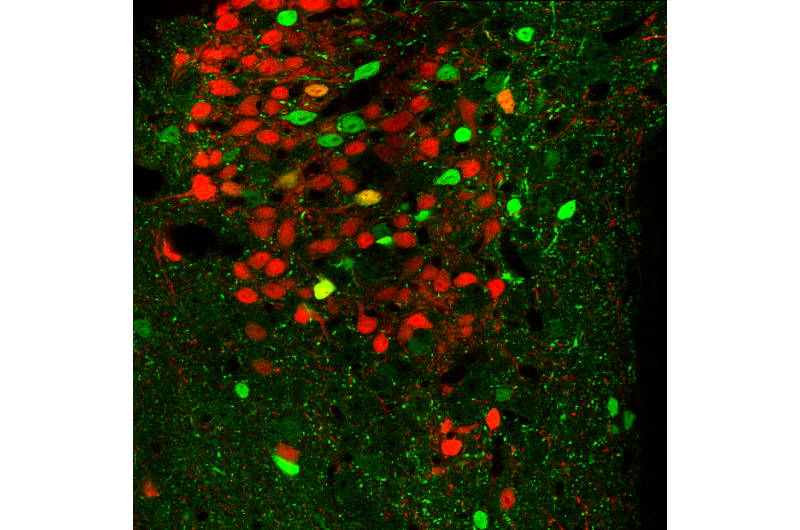

Working with Prof. Nicholas Justice's group at the University of Texas, Houston, Chen, Ramot and their group first characterized this special population of nerve cells, labeling them with fluorescent proteins in the brains of genetically engineered mice. When they removed the adrenal glands of these mice, and thus prevented the production of cortisol, the receptors did not appear on the PVN nerve cell walls, while injecting synthetic stress hormones caused them to appear and restart the chain reaction.

Next, the researchers asked when and how the CRFR1 cycle is initiated. They compared mice genetically engineered to lack the receptor with a control group and exposed them to different kinds of stress, testing the hormones in their blood afterward. When the mice experienced acute stress, both groups reacted in a similar manner, and their hormone levels were also similar. But chronic stressors told a different story: The genetically engineered mice stayed calmer and had lower levels of the cortisol-like hormone.

"In other words," says Ramot, "the CRFR1 system is a separate one that evolved to deal with chronic stress." Chen adds: "Some studies have shown that patients suffering from depression have more of this receptor than average, and this suggests further avenues of research and even ways to treat, in the future, disorders that arise from chronic stress."

More information: Assaf Ramot et al. Hypothalamic CRFR1 is essential for HPA axis regulation following chronic stress, Nature Neuroscience (2017). DOI: 10.1038/nn.4491