Mechanical forces control cell fate during brain formation

A new study coordinated by the Research Group in Developmental Biology at UPF shows that during the embryonic development of the brain, the cells that are between adjacent segments detect the mechanical forces generated during morphogenesis to regulate the balance between progenitor stem cells and differentiated neurons. The study has been published in the journal Development.

In vertebrates, the central nervous system is formed from an embryonic structure divided into three vesicles of the brain and the spinal cord. The rearmost brain vesicle will give rise to important adult derivatives such as the cerebellum and is where the cranial nerves that innervate the face derive from. During embryonic development, the hindbrain is subdivided into seven segments, called rhombomeres where neuronal progenitors are generated that will give rise to both motor and sensory neurons.

During segmentation of the hindbrain, a specific population of cells is located at the interface between successive rhombomeres. These boundary cells act as a barrier so that neighbouring cell populations do not mix, send instructions to progenitor cells of the adjacent rhombomere, and act as a source of progenitors and neurons. Although mechanical signals have been seen to be increasingly involved in directing cellular behaviour, how this happens in vivo had not yet been demonstrated.

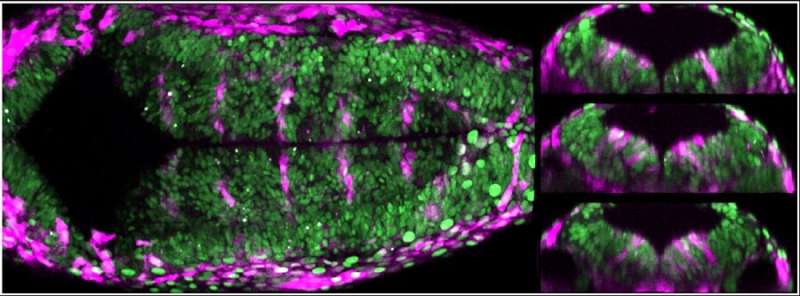

Now, the group led by Cristina Pujades at the Department of Experimental and Health Sciences (DCEXS) at UPF has investigated how these boundary cells are able to "sense" the mechanical stimuli and transduce them into specific biological behaviours during zebrafish hindbrain segmentation.

"Using transgenic zebrafish embryos that express fluorescent markers under the control of mechanical signals, we show that boundary cells in fact act as mechanosensors, through the activity of Yap/Taz-TEAD proteins," explains Adrià Voltes, first author of the article. This activity is lost when the authors manipulate the actomyosin cytoskeleton in both whole embryos and clonal populations, indicating that the pathway responds to mechanical cues in a cell-autonomous manner.

However, the decreased activity of these proteins, either conditionally or by yap and taz mutants, decreases the number of proliferating boundary cells but does not affect their differentiation into neurons. "Therefore, the activity of Yap/Taz-TEAD is essential to maintain boundary cells as proliferating progenitors and therefore as a niche for stem cells," explains Cristina Pujades.

Taken together, these data show that the boundary cells in the hindbrain sense mechanical forces through Yap/Taz-TEAD to regulate the proliferation of progenitors during segmentation. "Based on our results, we propose that the mechanical forces generated during the process of embryonic development regulate the maintenance of the progenitors and, therefore, control the balance between the proliferation and the differentiation of neurons," concludes Cristina Pujades.

More information: Adrià Voltes et al, Yap/Taz-TEAD activity links mechanical cues to progenitor cell behavior during zebrafish hindbrain segmentation, Development (2019). DOI: 10.1242/dev.176735