This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Old motor neurons don't die, scientists discover—they just slow down

A new study led by researchers at Brown University's Carney Institute for Brain Science offers a blueprint to help scientists prevent and reverse motor deficits that occur in old age.

As humans age, tasks that require coordinated motor skills, such as navigating stairs or writing a letter, become increasingly difficult to perform. Reduced mobility caused by aging is strongly associated with adverse health outcomes and a diminished quality of life.

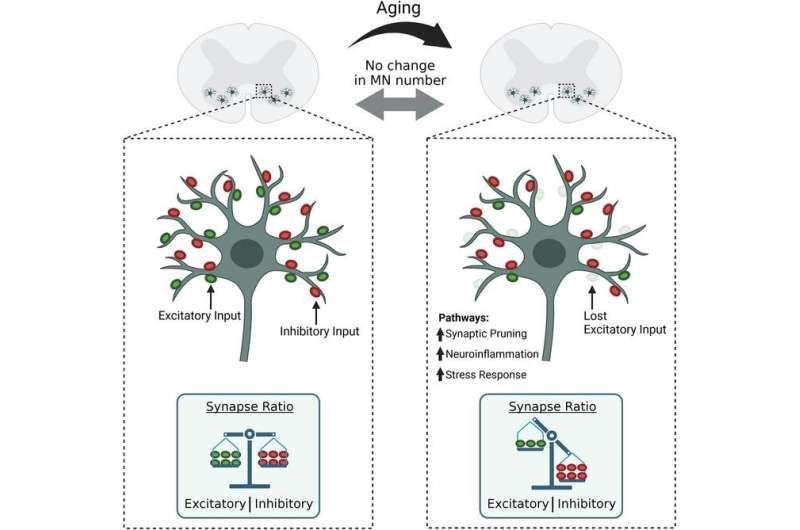

Researchers at Brown led by Gregorio Valdez, an associate professor of molecular biology, cell biology and biochemistry, discovered that the loss of connectivity of motor neurons in the spinal cord—not the death of those neurons, as was previously thought—is what impairs voluntary movements during aging.

"This is an important fundamental discovery because it tells us that treatments are possible to prevent and reverse motor deficits that occur as we age," said Valdez, who is affiliated with both the Center for Translational Neuroscience at the Carney Institute and Brown's Center on the Biology of Aging.

"The primary hardware, motor neurons, are spared by aging. If we can figure out how to keep synapses from degenerating, or mimic their actions using pharmacological interventions, we may be able to treat motor issues in the elderly that often lead to injuries due to falls."

For the study, published on Wednesday, May 10, in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight, researchers examined spinal motor neurons in three species, including humans, rhesus monkeys and mice.

"These findings revealed that, as individuals age, motor neurons lose many of the connections that direct their function," said Ryan Castro, first author of the study, who earned a Ph.D. in neuroscience from Brown in 2022.

Spinal motor neurons connect the central nervous system with skeletal muscles. The neurons receive and relay signals at synapses to activate the muscles needed to perform a specific movement. Because of their critical function, Valdez said, the loss of either motor neurons or their synapses would impair voluntary movements.

The number and size of motor neurons do not significantly change during aging, the researchers discovered. However, they undergo other processes that contribute to aging.

"Aging causes motor neurons to engage in self-destructive behavior," Valdez said. "While motor neurons do not die in old age, they progressively increase expression of molecules that cause degeneration of their own synapses and cause glial cells to attack neurons, and that increases inflammation."

Some of these aging-related genes and pathways are also found altered in motor neurons affected with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The researchers now plan to pursue studies to target molecular mechanisms they found altered in motor neurons that could be responsible for the loss of their own synapses with advancing age.

More information: Ryan W. Castro et al, Aging alters mechanisms underlying voluntary movements in spinal motor neurons of mice, primates, and humans, JCI Insight (2023). DOI: 10.1172/jci.insight.168448