Findings point to an 'off switch' for drug resistance in cancer

Like a colony of bacteria or species of animals, cancer cells within a tumor must evolve to survive. A dose of chemotherapy may kill hundreds of thousands of cancer cells, for example, but a single cell with a unique mutation can survive and quickly generate a new batch of drug-resistant cells, making cancer hard to combat.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have uncovered details about how cancer is able to become drug resistant over time, a phenomenon that occurs because cancer cells within the same tumor aren't identical—the cells have slight genetic variation, or diversity. The new work, published October 20 in PNAS, shows how variations in breast cancer cells' RNA, the molecule that decodes genes and produces proteins, helps the cancer to evolve more quickly than previously thought. These new findings may potentially point to a "switch" to turn off this diversity—and thereby drug resistance—in cancer cells.

"It's an inherent property of nature that in a community—whether it is people, bacteria or cells—a small number of members will likely survive different types of unanticipated environmental stress by maintaining diversity among its members," says the senior author of the new work, Beverly Emerson, professor of Salk's Regulatory Biology Laboratory and holder of the Edwin K. Hunter Chair. "Cancer co-ops this diversification strategy to foster drug resistance."

Instead of looking at a single gene or pathway to target with cancer therapies, lead author Fernando Lopez-Diaz, Salk staff scientist, and the team aim to uncover the diversification "switch" by which cancer cells replicate but vary slightly from one another. Turning off this cellular process would strip cancer's ability to survive drug treatment.

"Cancer isn't one cell but it's an ecosystem, a community of cells," says Emerson. "This study begins the groundwork for potentially finding a way to understand and dial back cell diversity and adaptability during chemotherapy to decrease drug resistance."

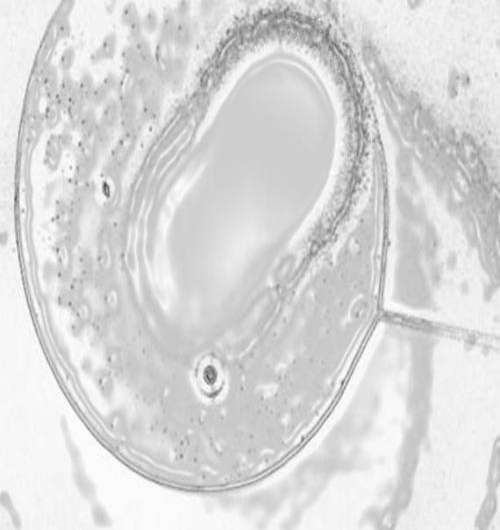

To uncover how groups of cancer cells achieve functional diversity (through RNA) to survive chemotherapy, Lopez-Diaz dosed dishes of human pre-cancer and metastatic breast cancer cells with the cancer drug paclitaxel for a week and then removed the drug for a few weeks, mimicking the treatment cycle for a cancer patient. Surviving cells—usually one or two out of millions—began to repopulate but with subtle changes in their RNA, presumably enabling them to survive future doses of the cancer drug.

By pushing the boundaries of bioinformatics, a collaboration led by Mei-Chong Wendy Lee and Nader Pourmand at the University of California, Santa Cruz charted more than 80,000 pieces of RNA per new cancer cell—typically, single-cell studies by other approaches look at hundreds or so RNA pieces to distinguish fairly different cells from one another. This unusually thorough list helped the researchers tease out subtle differences between generations of same cancer cells treated with chemotherapy and chart how the cancer cell community increased diversity among its members through RNA.

"We found an overwhelming return to diversity after chemotherapy treatment that couldn't be explained by expected mechanisms," says Lopez-Diaz. "There is something else going on here, a 'philosopher's stone' to cancer cell diversity that we now know to look for."

And when the team analyzed the gene expression profiles of the surviving cancer cell line, they were again surprised. "We thought they'd look like stressed cells with a few changes," says Emerson. "Instead, after a few population doublings they go back to the normal gene expression pattern and rapidly reacquired drug sensitivity." This adaptive behavior, Emerson speculates, lets the group of cancer cells prepare for the next unanticipated threat.

Another intriguing finding of the paper was that a high percentage of precancerous cells that underwent chemotherapy survived and proliferated, more so than either normal or cancerous cells. This led the pre-cancer cells to become more drug tolerant once they became a tumor. "The pre-cancer cells, when exposed to chemotherapy, evolved much faster and create a more drug-resistant state," says Lopez-Diaz. "This and other findings can now be explored into greater detail using the knowledge and perspective we have gained here."

More information: Single-cell analyses of transcriptional heterogeneity during drug tolerance transition in cancer cells by RNA sequencing, PNAS, 2014. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1404656111