New cancer therapy takes personalized medicine to a new level

Personalized care has been a buzzword in medicine for years, but new research on cancer treatment is taking it to a new level.

Detailed in a study published Thursday in Nature, the new approach combines several cutting-edge technologies to provide perhaps "the most complicated" treatment ever given. But by targeting a patient's own tumor from within, it also offers the possibility of successfully treating people who are out of options.

"I would call this a glimpse into the future of cancer therapy," said Dr. Michel Sadelain, a physician-scientist who directs the Center for Cell Engineering at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and was not involved in the research.

The study showed it can be feasible and safe to turn the immune system against cancer using a highly personalized approach, Sadelain said.

Dr. Antoni Ribas, who helped lead the work, said it's the most complicated treatment he's ever given. And in this early trial, it didn't cure or even much help the 16 patients who received it.

But the promise, the ability to give people an effective treatment individualized across many different variables, could open a new era in cancer therapy.

"If we turn on the immune system the right way, the immune system has memory and can lead to long-term responses," said Ribas, a professor of medicine at UCLA and at UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

"The leap forward here is we have tackled several problems at a time to advance a new form of cell therapy," he said. "Now we have to optimize it."

Fighting cancer

The big challenge in fighting cancer is that cancer cells look pretty much the same as every other cell. Chemotherapy and radiation are as targeted as they can be, but still kill off lots of healthy cells, which is why they make people sick.

Cancers, like viruses, evolve. That's why it's crucial to do what this trial did and attack the cancer from multiple directions at once, said Dr. Kai Wucherpfennig, chairman of the department of cancer immunology and virology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

"It's very important to try to anticipate what the escape routes are for the tumor, so you try to block them," said Wucherpfennig, who was not involved in the new study.

Ribas and his colleagues at PACT Pharma, a South San Francisco biotech company, combined four cutting-edge strategies to distinguish cancer cells from non-cancer cells.

First, Sadelain said, they were able to analyze genetic mutations in the tumor cells. Then, they identified immune cells in the patient's own body that could recognize those mutated cells. From there they were able to figure out what made those immune cells so effective. And finally, they genetically engineered the patient's own immune cell so more of them could identify and kill tumor cells.

"What it ultimately shows is that this is feasible," Sadelain said. "You can string together all these steps and reach a point where you have these cells to give to some of your patients."

Detailing the battle

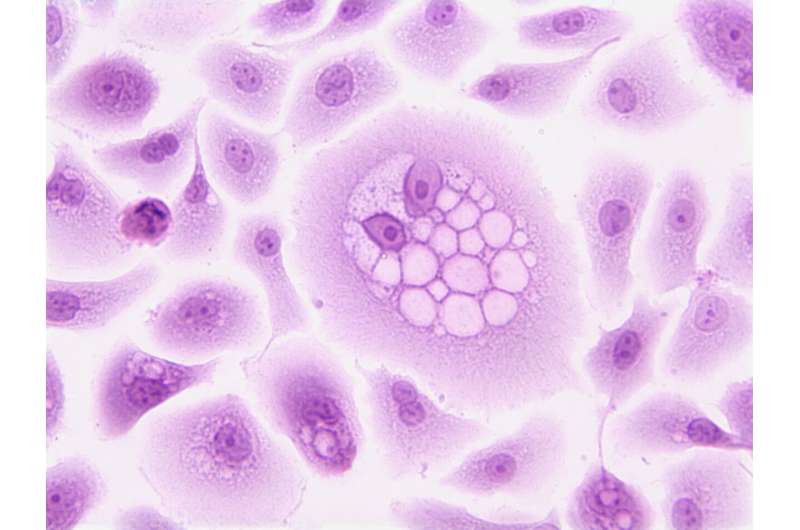

Every cell in the body has a series of receptors, essentially flags, on its surface. Finding and killing only those cells flagged as part of a tumor offers a way to fight cancer.

In blood cancers, most tumor cells have the same flag. Attack those with a CD19 flag, for instance, and most people with acute lymphoblastic leukemia will be successfully treated if not cured. Some healthy cells also carry CD19 flags, but people can live without them.

But in solid tumors, like lung, breast, colon and prostate cancers, the cancer cells carry all sorts of flags also commonly found on cells needed for survival. Using the new approach, researchers essentially identified the series of flags most likely to be found on tumor cells and gene-edit immune cells to attack them.

The goal, Ribas said, is to get the great results seen with blood cancers in these solid tumors. "To at least have a chance of treating solid tumors with a cell therapy that has been given the GPS to recognize the solid tumor because it recognizes mutations that are in the cancer cells and not in the normal cells."

Researchers altered the immune cells using CRISPR gene editing.

This offered a few advantages, said Dr. Katy Rezvani, an oncologist and section chief of cell therapy at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who was not involved in the research.

Normally, viruses are used to engineer cells, she said, but viruses can insert themselves into cells randomly, take a long time to manufacture and are expensive.

CRISPR, a Nobel Prize-winning approach to gene editing, allowed the researchers to make multiple, precise edits to the same cells. Once automated, this process can move much faster than would be possible with a virus and for far less cost, she said.

"You can build on this. You can make it better and more potent and faster," Rezvani said. "In the next five years or so, we are going to see many more of these cell therapies that will be using CRISPR as a genetic tool enter the clinic."

The new study was too small and the technology too premature to provide real benefit to the patients involved. Only the last patient, who received the most cells, the best editing and had the clearest mutations, saw short term improvement in their cancer, he said.

Future research has to be directed at increasing the power of the cells to provide more benefit to patients, Sadelain said. He and others are working on that.

"There are years or even decades ahead of us where we can hope that these various steps will be simplified, roboticized ... streamlined," he said. "While today it looks like a heroic effort, someday, this will be more widespread and much cheaper."

More information: Susan P. Foy et al, Non-viral precision T cell receptor replacement for personalized cell therapy, Nature (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05531-1

(c)2022 USA Today

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.